Red Fox Moult

It is debatable whether foxes undergo one or two moults per year, and many authors simply consider them to have a single protracted moult each year (lasting for much of the summer). Indeed, it's important to consider that moulting is an epigenetic process triggered, it appears, by changing light levels, and thus geography and the individual's genetics will influence the timing. Some anecdotal evidence suggests that age may also influence the timing and duration of the moult, with older animals losing and regrowing their coat more quickly than younger ones, but I'm not aware of any empirical data on this.

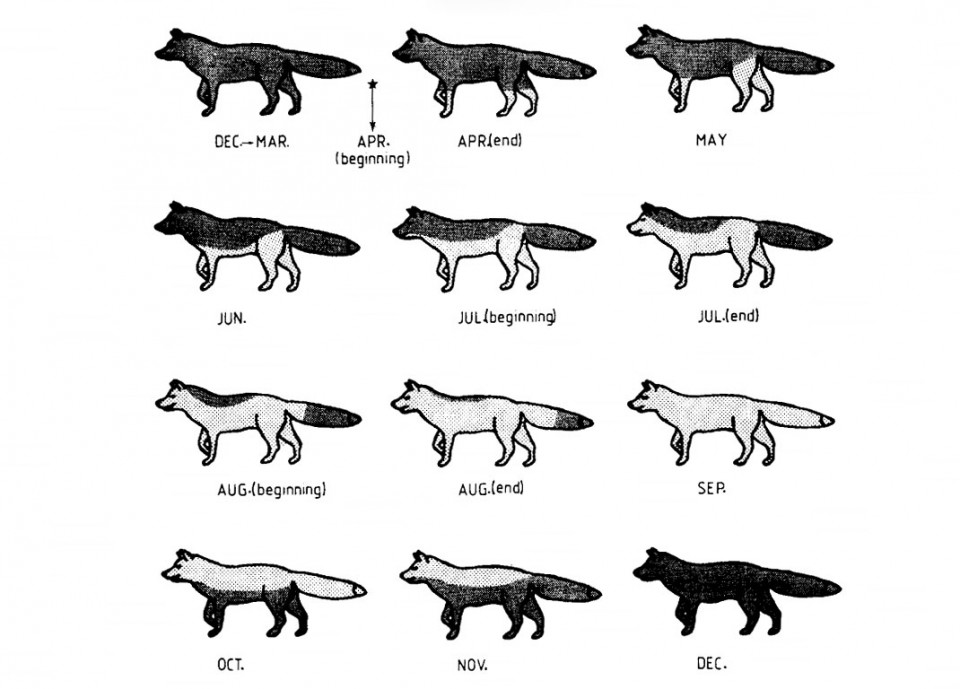

Daniel Maurel and his team described two moults in his French foxes: a spring moult where the old winter coat was lost and an autumn moult during which underfur grew in. The foxes started shedding in early April and the coat lost its lustre; by the end of the month new growth had started at the base of the legs. New hair growth progressed up the legs and, by the end of June, the summer coat completely covered the legs, abdomen and flanks; growth on the back and tail was complete by late August or early September (this was the summer coat) and then there's something of a hiatus for a month or so. At the cellular level, hair follicles undergo four phases: anagen, during which hair cells proliferate and the hair grows; a "remodelling" phase called catagen, during which the hair stops growing; the "resting" phase known as telogen in which the hair fibres are retained until the moult starts in the spring; and exogen when the hair is shed.

During October and November, Maurel and his colleagues recorded growth of some of the fine (underfur) hairs that hadn't grown during the summer -- this thickened up the coat in time for winter. The coat itself provides excellent insulation, although in a patchy manner; illustrated nicely by a fox filmed with a thermal imaging camera for the BBC's Autumnwatch in 2015. The thermal image showed the fox losing heat from its face, ears and legs, with less emanating from the shoulders and the top of its back, and the neck and flanks losing less still (i.e., being well insulated); the brush was almost invisible on the image (i.e., was losing virtually no heat to the environment) - see General Appearance, Coat Composition & Insulation for more. Overall, data from Alaskan Red foxes suggest that their winter coat keeps them well insulated down to about -13C (8.6F).

In Britain and Europe, the coat is in best condition from about November to February. Some foxes may begin to moult in late February, but most don't start until April and the protracted nature of the moult can lead to a "piebald" appearance during much of the spring and early summer. Often, breeding vixens begin to moult before barren vixens or males and can look very "tatty" or "mangy" for much of the late spring. Indeed, moulting foxes are frequently mistaken for animals infected with mange, but it's important to recognise that where the old coat is lost during a moult it is immediately replaced by new growth - sarcoptic mange results in bald patches that spread and the resulting skin often becomes injured as a result of repeated scratching. From late January or early February the hairs become brittle and the tips break, so the coat begins to lose its condition and worn patches may become apparent on the back and rump.

Hormonal studies on fur farm foxes have demonstrated that the moult is controlled by endocrine glands and stimulated by light such that altering the photoperiod (i.e., making the day appear longer or shorter) or thyroid/hormone levels can cause the moult to speed up or slow down accordingly. Some reports suggest that a warm autumn can delay moulting by a week-or-two, while an early frost accelerates it. Interestingly, there is some evidence that the moult progresses differently in silver foxes; one 1948 study documented a single, spring, moult that started at the rear and moves forward. There is also some evidence that the moult causes behavioural changes in foxes, particularly older animals. In his fascinating book, My Life With Foxes, Eric Ashby notes how:

"The coats of cubs do not undergo this change during their first year but continue to grow consistently as their bodies increase in size. Their first moult, during their second year, has little adverse effect on the youngsters. As they age, however, the moults tend to induce lethargy and apathy, causing them to sleep more, particularly in the hot summer weather when moulting begins."