Red Fox Breeding - Gestation, Birth & Litter Size

Most successful matings will occur during late January or early February (September and October in Australia) and, following successful fertilization, embryos enter the uterus about five days after mating and implantation occurs five to 16 days later, when progesterone levels (need to sustain pregnancy) are at their peak. Assuming successful implantation, the vixen will begin a gestation (pregnancy) that can last between 49 and 58 days; typically, Red foxes gestate for 52 days (around 7.5 weeks or just under two months). According to Mark Cardwine, in his 2007 Animal Records book, Red foxes have the shortest gestation of the dogs -- domestic dogs, by comparison, gestate for 58 to 65 days, African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) for 69 to 73 days and bat-eared foxes (Otocyon megalotis) for between 60 and 75 days.

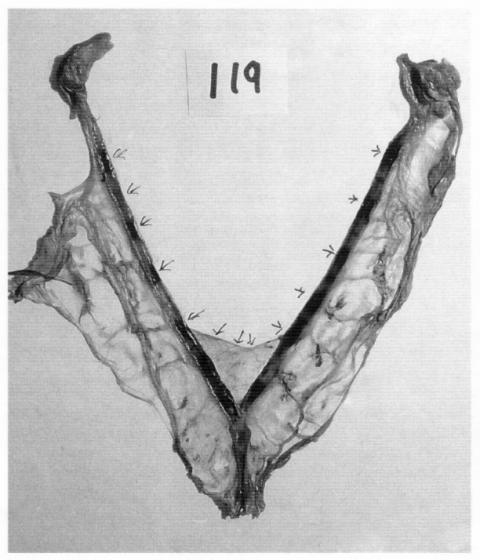

Foetuses can be lost at any time between conception and birth and, if this happens, they are then re-absorbed; this is a normal part of fox (indeed mammal) reproductive biology. In Wales, Huw Gwyn Lloyd found that an average of about 10% of pregnancies didn't make it to term, although in some years this reached 22% while in others losses were negligible. We can get an indication of how many foetuses make it to term and how many are resorbed by looking at the vixen's uterus. Like most mammals, foxes form a placental connection to their young and these connections to the uterus leave their marks. Indeed, since at least the 1930s we have known that scars on the uterus lining can be used to estimate successful births in mammals. The technique has been used in foxes since at least 1949, when New York biologist William Sheldon used the technique on American Red and gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus).

In a 2000 publication for the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Jonathan Reynolds summarised the topic of placental scar counting in Red foxes. Reynolds described how, post-mortem, the scars on the uterus -- each of which signify the site of a developing foetus -- can be used to assess litter size. Dark scars are left by the placenta once it has disconnected from the uterus and indicates a successful birth; immune cells called macrophages migrate to the disconnection site and begin breaking down the blood, leaving haemosiderin and lipids, which give the scar its colour. If the foetus is resorbed all that persists is a faint (pale) scar on the uterus marking its position.

In theory, counting the number of dark and light scars on a uterus should tell you how many ova successfully implanted and the number that made it to birth. In practice, however, this requires practise and it can often be difficult to distinguish aborted foetuses from the scars from the previous year's births (which fade in time and may persist for longer than traditionally believed). Such counts can also overestimate litter size because it cannot distinguish live and still births, or between births and very late-term abortions. It can, nonetheless, often be used to good effect and, in 1970, Jan Englund developed a greyscale scale (with six shades) to distinguish active (birth) from old (previous births) or resorbed scars.

Over subsequent years, various authors have improved upon the method and, in 2011, French biologists Sandrine Ruette and Michel Albaret published an improved method that involved staining the scars. With this they were able to positively identify scars relating to successful births (and less ambiguously than using a colour card), but couldn't separate previous births from abortions. Additionally, the timing of collection can have an impact and, in his comprehensive review of the Red fox in Ireland, published in 1970, University College Galway zoologist James Fairley noted that placental scars had disappeared by late proestrus, presumably because new endometrial tissue grows during this period, covering them over. In the end, it is the number of young born that interest those involved in fox conservation and management and hence such methods are aimed at addressing this.

In his fascinating 2000 book, My Life with Foxes, the late New Forest naturalist Eric Ashby described how the signs of pregnancy are not immediately obvious in vixens, with the size and shape of the mother being only slightly altered by the tiny unborn cubs. It seems that the first indication is an increase in appetite, followed by a surge in the hormone prolactin which causes the teats to swell and change from their pale colour to be bright pink and prominent - simultaneously, the fur around the teats becomes bare.

The natal earth

Assuming all's well, the vixen's mammary glands emerge about two weeks before the young are due to be born and, at around the same time (late February), the vixen becomes extremely secretive as she starts looking for an earth in which to give birth (a natal earth). She may dig a new earth, or use a previous one -- underneath sheds and out-buildings are popular natal earth sites, as are sites under gravestones (see Dens/Earths). Ashby noted that his male fox, the father of the cubs, became very attentive shortly before the cubs were born -- following the vixen almost everywhere, sleeping beside her and bringing her presents of food and toys. We know little about what happens in the wild, but we have data from captivity. Indeed, based on 19 vixens held at the Agricultural University of Norway's fur farm between 1984 and 1990, Bjarne Braastad reported in his 1993 paper to Applied Animal Behaviour Science that the females spent 63% of their time in their den, mostly resting or sleeping in the 24 hour immediately prior to giving birth; digging was the most common activity during this period. Over the three days postpartum, about 70% of a vixen's time was spent resting or sleeping, although any given bout of sleep was short, lasting 11 minutes on average, as the females were frequently disturbed by the cubs.

In most habitats, the only period during which a den is almost essential is the breeding season. In some cases a fox will give birth above ground in the trunk of a fallen tree, a tussock of grass or in a log pile, but such instances are rare. Where an al fresco birth does happen, it may have been that the vixen was forced to leave the earth for some reason and was "caught short". Indeed, in Running with the Fox, David Macdonald described finding five mole-grey newborn foxes nestled cosily in a dry tussock of reeds bordering a duck pond. Later that night, having disturbed the vixen, Macdonald watched her move the youngsters to a nearby earth under an oak tree.

Most foxes, it seems, are born underground. In the days leading up to and following birth, the vixen is typically sustained by food brought to her by the father and, in some instances (as we'll come on to shortly), subordinate vixens in the social group. The vixen generally does not allow the dog access to the young while they remain in the earth (the first sight he apparently gets is when they appear above ground) and he leaves food at the entrance. No scats will be deposited in the vicinity of the earth during this time.

When it came to the births, Braastad observed that delivery of the cub was generally straightforward. The vixens gave birth lying on their side and the head appeared after a few minutes of labour contractions and genital licking, at which point the vixens pulled the cubs out with their mouths and licked them dry. Cubs were born throughout the day and night and typically did not suckle until the whole litter had been delivered and licked clean. After the first cub was born, Braastad found the visible labour between subsequent births was only about five minutes, although the duration between births could be nearly an hour. On average, litters were complete in 192 minutes (i.e., just over three hours). Most vixens did not leave the nest box for the first 12 to 15 hours after the cubs were born, and one female remained holed up for 27 hours after birth. When they did go outside, cubs were left for no more than about 10 minutes. When the vixen left, the cubs huddled together for warmth.

Family planning - litter size

The largest unconfirmed litter I have come across is 14 young -- usually called cubs (UK) or kits (US), but occasionally pups -- and while there is a confirmed case of a vixen from Tippecanoe County in Indiana having 13 cubs, the mixing/pooling of the litters of two or more vixens in a social group may account for many such large counts. We don't know how frequently vixens pool litters, although we suspect it's more likely in resource-abundant urban settings. A significant difference in the size of cubs accompanying a vixen is often taken as evidence of litter pooling, but Huw Lloyd, in his 1980 opus The Red Fox, described the case of a captive vixen whose litter of four cubs he observed at about four weeks old. Two of the cubs looked like month-old foxes, while the other two were much less well developed and had the appearance of younger animals. Removal of the larger cubs from the vixen for a couple of hours a day resulted in the smaller cubs rapidly catching up their littermates. Lloyd cautioned that:

"Had this litter been found in the wild, it would probably have been regarded as evidence of the pooling of two small litters, the appearance of the two larger and two smaller cubs being so dissimilar."

As well as litter pooling, there are anecdotal reports of cubs being adopted. In July 2021, a lady in Kent reported eight well-grown fox cubs feeding together in her garden. According to her observations, this family started out with four cubs, which grew to five as a different cub, darker in colour and much bolder (e.g., didn't wait for the adult vixen to eat first, like the other cubs, and of which the other cubs seemed nervous) turned up on 10th June. From five, the litter increased to eight and the observer's opinion is that the family is essentially fostering these other cubs, rather than them being part of the same litter but not having put an appearance in until now. The cubs are all around the same size/age going by the photos. In a slightly more extreme example, during a deterrence check at a dilapidated stable building in March 2021, four cubs of clearly different ages were found together in the same den site; two were about a week old and two four or five times larger at an estimated 3 weeks old. In this example, only one adult was ever seen going into the stable (although it should be cautioned that this doesn't exclude the presence of a second individuals that evaded observation) and it remains unknown which litter belonged to the current mother - she appeared to be caring for both, though. The cubs were removed the day after her visit, the observer presumes by the same vixen.

Vixens typically have four pairs (eight) of mammae (nipples), although as few as six and as many as 10 have been reported, suggesting they would struggle to raise very large litters. Indeed, Lloyd was certain that a wild fox can't successfully nurse a litter of more than ten cubs unaided.

The average litter contains four to six cubs, with eight being the largest that a single vixen in the UK is likely to produce. Interestingly, litter size is relatively constant across years and it seems that even where foxes are heavily controlled (causing a reduction in the population density) the population responds by increasing the number of vixens breeding, rather than by increasing the number of cubs in the litters. This makes sense when we consider that culling reduces density and increases the number of available territories, meaning it is easier for a fox to strike out on its own and free herself from the breeding suppression imposed by her mother. Hence, more vixens have litters, while litter size itself is correlated with the physical size (not necessarily weight) of the vixen, which is independent of available territory. That said, there are some data to suggest that the number of cubs in the litter can also vary according to habitat.

Experiments by a group of scientists based in Spain, for example, found that foxes in the "vegas" (their term for favourable habitat) had larger litter sizes than those in the "steppe" (less favourable habitat). The vegas population also had a higher number of barren vixens than the steppe -- 19.3% and 1.7%, respectively -- which presumably reflects breeding suppression by dominant vixens in favourable habitat. Similarly, an outbreak of rabbit haemorrhagic disease in Spain during 1988 caused a substantial (90%) decline in rabbit numbers -- the staple food of these foxes -- and caused a decline in the average litter size that ultimately led to a reduction in fox abundance.

Battle of the sexes

Interestingly, habitat quality doesn't only impact the number of breeding vixens on a territory; it can also influence the sex ratio of the litter and this, in turn, can affect the date the cubs are born. We now know that mothers invest more energy producing males than females and vixens living in high quality habitat tend to be larger than those in poorer areas, putting them in a better position to cope with the higher energetic demands of male cubs: these individuals thus tend to produce more male cubs (although they don't have larger litters), while smaller vixens tend to produce more female cubs.

For many years we have known that male cubs are typically born larger than vixens (dogs were 11.4% heavier than vixens in one study of Welsh 45 litters by Huw Lloyd), which implies that even in the womb the mothers are feeding their male cubs more than female ones. During his studies of foxes in Wales, Lloyd also recorded an interesting shift towards male cubs as gestation progressed. Lloyd looked at the sex ratio of 333 embryos from 68 litters and found that early in gestation the sex ratio was slightly female biased (with 48.9% being male), but by the time the mothers were 40 days from giving birth the ratio had shifted slightly in favour of males (51.5%). This shift isn't huge (only 2.6%), but it does suggest that male embryos have a higher survival rate than female ones; in an article to the July 2012 issue of BBC Wildlife Magazine, Stephen Harris goes a bit further, suggesting that vixens may preferentially abort female embryos.

Recent work at Bristol University by Helen Whiteside has found that the number of males in the litter also has a bearing on when the vixen gives birth. Logically, you could be forgiven for expecting that litters with more dogs than vixens should be born earlier, allowing more time for the male cubs to grow and prosper, but quite the opposite is observed, as Harris explained in the aforementioned article. During her Ph.D. studies, Whiteside found that male-dominated litters were born later than vixen-dominated ones; this allows the cubs to be weaned at the point that their main prey (rabbits and voles) start breeding and should thus mean an abundance of solid food for them. If the cubs are born early, they're weaned before this mammal 'glut' and are more dependent on earthworms and insects in the interim, which are less predictable. If it is a hot, dry summer these invertebrates are difficult to find and this can severely impact the growth of the cub.

Cubs reach their adult size by the autumn, so they can't 'make up' for any growing lost through a dry summer and, thus, having a bountiful supply of young mammals to fall back on can make all the difference. Male cubs, it seems, grow faster than females both when suckling and when weaned on to solid food. Why should this be important? As we'll see later, size is important for males (larger cubs become larger adults that are more likely to find and keep a territory and thus more likely to father more cubs than smaller males). For females, size doesn't have the same implications in later life and a small vixen is just as likely to breed as a larger one.

Dropping litter. When are cubs born?

The peak time for births in the UK is mid-March, although cubs can be born any time from late January until well into April. There are even a few very early records. although confirmed records remain rare. Brian Vezey-Fitzgerald, recorded fox cubs above ground in his garden on 5th January 1963, during the very harsh winter with thick snow cover; working backwards, this suggests they were born in early December and that the was vixen fertilized in October. Additionally, a fox cub was brought into The Fox Project on 25th February 2013; it was estimated to be about four weeks old on admission and is therefore likely to have been born in late January. More recently, a long-running national Echinococcus multilocularis survey reported two early breeding vixens in 2022, described by Graham Smith and colleagues in a 2023 paper to Mammal Communications. One female shot on 20th November was lactating but not pregnant; presumably she had recently given birth and was thus mated in late September. The second vixen, shot on 15th December was heavily pregnant and lactating and, judging from the developmental state of cubs, was mated in late October. In his book, Town Fox, Country Fox, Vezey-Fitzgerald went on to describe how there was more variation in cub births in Europe:

"... in France and Belgium, births of wild fox cubs have been recorded in every month of the year except August: even births in June and July are not regarded as altogether exceptional."

In the UK, the latest litters tend to be born during April and, given the spontaneous nature of the Red fox's breeding biology, I generally treat unverified reports of very late fox cubs with considerable suspicion. That said, a fox cub estimated to be only three-weeks-old was taken in by South Essex Wildlife Hospital on 19th November 2013, after it was found in central London with no earth in sight. This represents that latest verified UK birth I have come across and, working backwards, suggests birth during the last week of October and successful mating around the 9th September.

Births in the UK appear to coincide with populations elsewhere in Europe. In a recent paper to Mammalian Biology, Zea Walton and Jenny Mattisson used GPS fixes to calculate that the peak time for cubs to be born by 30 collared vixens in Sweden and Norway was between 20th March and 14th May, with the average being the 12th April.

I would be very interested to hear from readers who have evidence of very early or late fox litters. In Australia, where seasons are reversed compared with the northern hemisphere, most mating occurs during June and July and fox cubs are typically born during August and September.