Foxes have an ability to polarise opinion like few other species on Earth. By and large, my experience has been that most people fall clearly into those who ‘like’ or ‘dislike’ foxes and it is comparatively rare to find those who are indifferent to them. For the purposes of transparency, I must say from the outset of this piece that I am broadly ‘pro-fox’. Their natural history fascinates me, as does the way we humans interpret and respond to their presence and behaviour. At the same time, being a practical person, I understand that foxes can cause problems for people and that there are times when some form of control is required.

Passions run high where foxes are involved and this makes reasoned debate difficult to come by; most discussions I have seen descend into mud-slinging sooner or later. As Hugh Kolb says in his book Country Foxes:

“Most people’s attitudes to hunting are based more than anything else on emotional reactions to something they are either unfamiliar with or which they have been brought up to regard as part of normal life.”

My aim here is to try and provide a summary of the subject and address some of the misconceptions that I see repeatedly in debates. Some of the information below is repeated elsewhere on the site, but I have tried not to rehash too much. There are links at the bottom of the article that will take the reader to more detailed QAs discussing some of the topics.

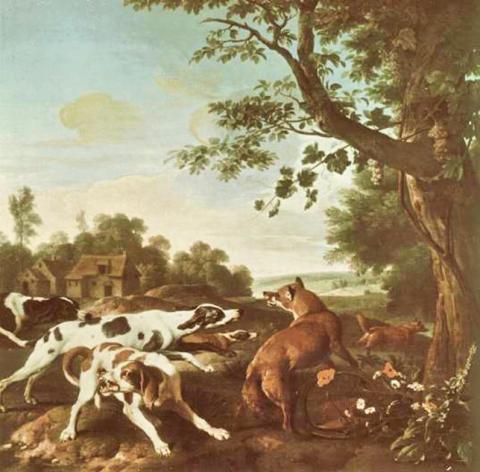

A Very Brief History of Fox Hunting in England

Fox hunting has taken place in the UK for almost 700 years. The first accurately recorded fox hunt, during which a farmer in Norfolk used his dogs to chase down a fox suspected of killing some of his livestock, was in 1534, although there are references to hunting foxes in England dating as far back as AD43. Following the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, hunting grew as a sport, although game was the primary quarry. The first British hunt was established during the 1670s in Yorkshire and, since then, a further 317 hound packs were registered. The fox hunting season in the UK was from November to April, with autumn (or ‘cub’) hunts starting in August.

Edward Bovill provides a fascinating anthology of the evolution of fox hunting in Britain in his book The England of Nimrod and Surtees, published in 1959, and the reader is directed to that for more detailed coverage. Essentially, however, fox hunting was a slow pursuit up until the 18th century – prior to this, hounds were bred for their nose and, according to Bovill, “they virtually walked their fox to death”. During the second half of the 18th century, Hugo Meynell began selectively breeding hounds for speed. The appearance of faster hounds coincided with the implementation of Inclosure Acts, which saw once common and publicly-accessible land fall into private ownership. In response to the Inclosure Acts, many miles of hedges were planted and fencing erected; woodland declining in response to a growing need for wood for fence posts. Faster hounds meant faster-paced hunts, while Inclosure meant obstacles such as gates, fences and hedges to navigate. In other words, fox hunting became more dangerous and this attracted followers from further afield.

Around the same time, fox numbers dropped in response to a loss of woodland cover and what appears to have been an outbreak of mange. The draining of land with enclosure made the fields more valuable and resulted in planting of crops, in which it was more difficult to hunt, and the need to move large quantities of coal saw construction of canals that represented impenetrable obstacles for hunts – these were followed by railway lines. Furthermore, a rise in the popularity of pheasant and partridge shooting meant that newly-employed gamekeepers took a heavy toll on the mounted hunts’ quarry.

Subscription packs that included followers from towns and cities many miles away were formed in response to the changing landscape and many farmers were less inclined to suffer the damage to their land when they did not know the hunters. Prior to this period of intense change, the open areas meant hunting was easier and less damage was sustained, not to mention the hunting parties were often small and composed of locals that an affiliation with the farmer – they were usually led by a wealthy squire with whom the farmer was far too well-disposed to interfere.

Changing attitudes and a reduction in foxes made hunting increasingly more difficult and secretive during the 19th Century. It also saw foxes imported from the continent, despite an apparent prejudice against foreign foxes that were considered by many to be of inferior quality, and even stolen from one part of the country and sold to a hunt somewhere else. Indeed, so great was the demand for foxes that criminal gangs were operating in parts of England and some squires were paying blackmail money to prevent their foxes being stolen. The popularity of mounted hunting increased again during the latter part of the 19th century and remained popular well into the 20th, when increasing opposition on animal welfare grounds began to manifest.

Opposition and The Hunting Act

Perhaps the first co-ordinated opposition to the practice of hunting foxes with hounds was brought by the Humanitarian League, which was founded by Henry Salt in 1891 to campaign against suffering in all its forms. Despite being the oldest British animal welfare charity (founded 1824), it was not until 1972 that the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) came out in favour of a ban on fox hunting; two years later, the Labour Party included an opposition to hunting in their manifesto for the first time. Probably the first real attempt to get hunting with dogs banned was a bill proposed by the Labour MP Kevin McNamara in 1992, which failed on its second reading. In 1993, Labour MP Tony Banks also failed to get the hunting bill passed and, in 1995, McNamara’s bill passed its second reading, but failed in the House of Lords.

On 14th February 2002, Scottish MPs voted 83 to 36 in favour of an outright ban on fox hunting that subsequently became law on the 1st August as the Protection of Wild Mammals (Scotland) Act 2002. This ban carries a penalty of six months in prison and a fine of up to £5,000 (about US$9,270 or €7,140). While the ban technically forbids the practise of hunting with hounds, it is worded such that mounted hunts can chase the fox, provided they have no more than two hounds and that the fox is either shot or killed by a bird of prey. Moreover, the ban still permits the use of terriers to flush out foxes that have "gone to ground", because the hunt is seen as a form of pest control.

In February 2003, a new hunting bill for England was ‘shelved’ owing to the ongoing conflict in Iraq. A crowded parliamentary program caused further delays to the bill and it was passed over into the autumn session of Parliament. In 2004, the Labour government reintroduced the bill, intending to apply the 1949 Parliament Act to force it through the House of Lords. At 6pm (GMT) on Thursday 18th November 2004, MPs voted 321 to 204 in favour of an outright ban on the hunting of foxes, deer, hare and mink with hounds in England, and Michael Martin (the Speaker of the Commons) overrode the Lords opposition by invoking the Parliament Act, ending years of Political ping-pong between MPs and the House of Lords.

Despite the success of the bill, things have not gone strictly as the Government had planned. The then Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair, had originally hoped to delay the implementation of the ban for two years, so it came into effect in July 2006. Labour stated that this delay was to give the hunting community time to adjust to the closure of their pastime, although those of a more cynical persuasion suspected it had more to do with the up-and-coming election, for which Labour had surely lost much of the rural vote. Instead, the Hunting Act came into force on 18th February 2005.

For those interested in reading more about the campaign to ban fox hunting, there is a more detailed history on the League Against Cruel Sports' website, while Historic UK provides a more balanced view on their website. Wikipedia has a comprehensive article on the Act, support and opposition and the legislation itself can be reviewed on the government’s website.

Response to the ban

With passion running high there were a great many claims that the law would be a disaster, unenforceable or was simply a waste of time and money. Many hunt supporters claimed that they would ignore the ban and continue hunting and (largely unsuccessful) legal action has been filed against at least 10 hunts since 2005. A common statement made in response to the Act was that it ‘wouldn’t save a single fox’ and, while missing the point (see below), this does seem to be the case.

According to data published by the Scotland on Sunday newspaper in November 2004, the number of foxes killed by Scotland's 10 registered hunts has increased from 500 to 900 per season because guns are more efficient than hounds. Similarly, in England, the British Breeding Birds long-term survey data suggest that sightings of rural foxes have declined steeply in recent years, particularly since 2010. There is some suggestion that this decline is in response to a reduction in the rural rabbit population, but circumstantial evidence suggests farmers and gamekeepers have felt compelled to target foxes more in the absence of mounted hunts.

There were claims that the Act represented an erosion of civil liberties, but to the best of my knowledge this was never challenged legally. Indeed, animal welfare supporters argue that a line must be drawn between what is and what is not an acceptable choice when it comes to our treatment of animals. That being the case, it is difficult to see how the ban on fox hunting is any more an erosion of freedom of choice or civil liberties than the Protection of Animals Act (1911 - with subsequent amendments) that makes it illegal to mistreat or cause "unnecessary suffering" to your cat or dog or the various laws that govern how we treat our fellow humans.

Foxes and fox hunting QA

For the purposes of both brevity and clarity, I have opted to split this article into a short selection of questions and answers. This allows me to directly address some specific statements that appear time and again during debates about hunting foxes. I must reiterate that the following constitutes my opinion on the subject and is based on the evidence available to me. I am always happy to hear from others who have a different experience or can provide additional data.

Fox hunting is not about cruelty, but about controlling pest/fox numbers in a "natural" manner. Is this true?

It is often stated that hunting with hounds mimics natural predation and so serves as a form of natural selection on the fox population. The old, weak and sick foxes are removed and the strongest and fittest animals survive to see another day. This is an attractive argument and, on first pass, appears legitimate, although it is difficult to assess because foxes have very few natural predators. In parts of North America and Europe foxes may be killed by wolves or bears, but such cases appear very rare and foxes instead seem to benefit from scavenging the carcasses left behind. Golden eagles and eagle owls also occasionally take foxes, but primarily cubs, and these animals swoop on prey rather than chase it for prolonged periods. Perhaps the three most significant "natural" predators of foxes are coyotes, dingoes and lynx, all of which can have significant impacts on fox distribution and abundance. Coyotes and, perhaps, dingoes will chase down foxes over short distances. Lynx, by contrast, are ambush predators and generally do not chase prey.

Some of the practices employed by hunts also appear to undermine the argument for mimicing natural selection - the use of terriers to flush foxes from earths and the digging out of foxes that have "gone to ground", for example. I’ve been unable to find any evidence that wolves, bears, coyotes, dingoes or lynx will try and dig out foxes. Similarly, the observation that most hunts appear to operate in response to fox problems, rather than assessing the fox population and removing "inferior" animals casts further doubt on the role of mounted hunts as a positive selective force. Finally, hunts using "bagged foxes" (i.e. those imported from elsewhere and released for hunting purposes) and actively boosting fox numbers through releases, habitat management and construction of artificial dens are well known historically. More recently, there have been media reports suggesting some hunts continue to breed foxes. Such activities would appear counterproductive if the aim was to control fox numbers.

What impact do mounted hunts have on fox populations?

We don’t really know. We know that culling, most notably shooting, can have an impact on numbers, particularly at a local scale, but it is immensely difficult to assess what contribution mounted hunts play. The mathematical models that have been used to investigate fox population dynamics suggest that to achieve a decline in fox numbers, there must be a population mortality of 64% or greater. Prior to the ban, hunts were estimated to account for somewhere between 6% and 10% of the foxes killed annually in Britain; in his 1996 book Country Foxes, Hugh Kolb considered this contribution "almost trivial".

The only attempt to assess the direct influence of mounted hunts on fox number of which I’m aware came in the wake of a serious outbreak of foot-and-mouth in the UK during 2001, which led to a ten-month cessation of fox hunting. In an oft-cited paper published in the journal Nature, Phil Baker, Stephen Harris and Charlotte Webbon at the University of Bristol reported that the ban on hunting during the outbreak had no significant impact on fox numbers (i.e. we did not see the 'explosion' in fox populations some had predicted in the absence of hunting). The study was commissioned by the Mammal Society and analysed the results of fox scat placement at a countrywide scale.

Foxes are territorial and by counting, removing and counting replacement droppings we can get an idea of territory occupancy. The study registered a slight increase in fox numbers in the east of England and a slight decline in foxes in southern England, but overall the number of fox scats declined by a statistically insignificant 4.7%, suggesting no change in the fox population. Not everyone agreed with the findings of this study, and the results were challenged by a team from the Game Conservation & Wildlife Trust (GCWT) and the Oxford University who argued that the Bristol team's analysis did not support their conclusions and accused them of using an "inappropriate statistic". The Bristol team responded to the challenge and, to my mind, defended their analysis.

We don’t need to control fox populations. They’re self-regulating.

Ecologically-speaking, the populations of all living things are self-regulating. In the most basic sense, a population increases until it finds something is limiting, usually food, water or space, at which point the population remains static or declines. The problem, though, is how many foxes is ‘too many’? Even if there’s only one fox in the neighbourhood, if it’s fouling your garden, taking your livestock or its mating calls are keeping you awake at night, it may be one fox too many. As Oxford University zoologist David Macdonald put it in an article to the BBC Wildlife magazine back in 1981, “it’s difficult to calibrate nuisance”. The situation is complicated further by Phil Baker (Bristol University) and Dawn Scott’s (University of Brighton) finding that fox sightings are not correlated with fox abundance. In other words, frequently seeing foxes around doesn’t mean there are a lot of foxes in the area. Foxes are individuals, some bold and some shy, which means some are more likely to cause problems than others.

In their 2000 paper to the Journal of Zoology, Matthew Heydon and Jonathan Reynolds of the GCT assessed the impact of culling foxes on a regional scale at three locations across the UK: mid-Wales, the east Midlands and East Anglia. The biologists found that active culling practises did have a demonstrable effect on the fox numbers in two of the three study areas (mid-Wales and East Anglia). Furthermore, Heydon and Reynolds reported that, in these two regions, fox populations were "demonstrably not self-regulating through suppression of breeding and were unlikely to be at an equilibrium determined by resources". In other words, fox numbers weren’t being controlled through resource competition. Furthermore, while their data indicated that fox populations were resource-driven in the east Midlands, the authors suggest that a reduction in culling effort here would lead to an increase in fox numbers.

Heydon and Reynolds put the regional variation they observed down to differences in land and livestock management. For example, community motivation and thus effort to control fox numbers is high in mid-Wales (for sheep farming) and East Anglia (for game hunting), while sport hunting has claimed preference over the last two centuries in the east Midlands. This takes us back to the idea that some parties have more of a vested interest in fox populations than others and are willing to tolerate less disturbance than others.

People should protect their animals better, rather than killing foxes

“If I can keep foxes in, you can keep foxes out.” That’s a one-liner I will always remember veteran fox rehabilitator Mike Towler telling me – and he’s right…most of the time. The keeping of small livestock as pets (domestic rabbits, chickens, guinea pigs and so forth), the onus is very much on the owner to ensure they have secure living quarters that cannot be breached by a predator. Many of us seem to simply expect predators, and particularly foxes in my experience, to understand and conform to our rules. We expect that the universe should care that we, as clever primates, want to keep chickens, rabbits, guinea pigs etc. in our gardens without fear of predators eyeing them up. We’re humans after all; the most important and powerful species on the planet. If predators fail to toe the line, if they behave in a way we don’t understand or appreciate, we brand them evil or malicious and consider this affront worthy of death. The truth, though, is that the universe doesn’t care about us, and foxes have no conception or appreciation for our moral code or desires. The rabbits in your garden look and behave just like the ones living on the school playing field or along the railway line, but yours are penned in, which makes them easier to catch.

Deterrence is far more practical than lethal control, because the turnover in our fox population, particularly in urban areas, is high meaning territories don't stay vacant for long; perhaps a week or two, based on very limited data. How easy deterring a fox (or foxes) is depends on a host of different factors, including how strong the attraction is and how determined the individual fox is. More information and suggestions can be found in my Deterring Foxes article.

The problem of excluding foxes or securing livestock is considerably more difficult for commercial operations, such as sheep and poultry farmers. We want justifiably demand free range eggs and chicken, for example. Providing a large area over which poultry, or sheep, can freely roam drastically improves the quality of their lives, but makes protecting them from predators with fencing much more complicated. It’s often possible, but it drives up the price of our meat and eggs. Similarly, indoor lambing significantly reduces mortality from predators, the elements and general birthing trauma – again, though, it is costlier than leaving the animals to roam the fields and this affects the price. In such instances, lethal control may be the only option.

Is it hunting with hounds cruel?

This will always be a contentious point. Hunters argue that the fox does not anticipate death and so is not unduly traumatised by the pursuit. This is one of many unknowns. We cannot be certain what a chased fox is thinking or feeling. For that reason, opponents of such hunting prefer to err on the side of caution - then there is no question.

Shooting is worse than hunting. Hounds kill foxes with a nip to the back of the neck, but shot foxes slink away to die from gangrene

I have spoken to many professional stalkers and farmers about this and the response is almost always the same. When carried out by a competent marksman with an appropriate calibre weapon, coupled with the use of a long-dog to track any "winged" animals, shooting is unquestionably the most humane method of lethal control. It’s possible that a fox may be wounded and escape, although I’m told that the use of a dog makes it very unlikely, and gangrene infection is a possibility. That said, I have never come across a report of gangrene in foxes in the literature and know of no rescue centres that have admitted gangrenous foxes for treatment. Indeed, quite the contrary; foxes have a remarkable ability to recover from injury and there are reports of apparently healthy foxes with sections of tissue missing from their jaws and cross-bow arrows protruding from healed wounds in their chests.

The “nip to the neck” argument, reference to severing of the cervical vertebrae and thus killing outright, is difficult to assess, but does not appear to be supported by the evidence. In the wild where dogs hunt in packs the hunting technique is a prolonged chase followed by multiple bite trauma. This appears relatively consistent with the post mortem results from foxes killed by mounted hunts. I have, however, only seen the summary results from one study from Bristol University that carried out post mortems on four foxes – all sustained multiple bites/disembowelment and in none of the cases was the fox’s neck broken. This is also consistent with the observations of hunt saboteurs and the videos of hunts I have seen. I would be very interested in empirical evidence to the contrary.

Even the Burns Report admitted that in some cases hunting with hounds was more efficient than shooting

The Burns Report noted that:

“None of the legal methods of fox control is without difficulty from an animal welfare perspective. Both snaring and shooting can have serious adverse welfare implications.”

There are situations, particularly in forestry blocks, where the use of dogs to flush foxes to competent marksmen is the only efficient method of fox control. Under such circumstances, there is an argument for the use of foot packs (i.e. men working dogs on foot on the trail of a fox) and this activity is still legal in Scotland. The dogs are used to drive the foxes out of the plantation to waiting guns. In most situations, however, stalking and shooting with a suitable calibre rifle by a competent marksman is the most humane method of culling foxes, deer and hare; the potential to cull more animals in a given time window also make this a more efficient method of control. The use of shotguns is generally considered inappropriate and the wounding rate likely to be higher than in cases where rifles are used.

Foxes are ruthless predators in their own right. Who cares how they’re killed?

About four-fifths of the population, according to an online poll for ITV in June 2017. Moreover, the manner of control says more about the person carrying it out than the animal being targeted. A friend of mine summed this up nicely a couple of years ago when she said:

“Foxes may have to be culled in some cases as an objective economic necessity to protect livestock, but there's something unhealthy and disturbing in making a party of it.”

Foxes kill for fun

This is covered in more detail in a QA, but I’ll summarise here for the sake of completeness. I think people expect too much of wildlife. Humans have a pretty well defined moral and ethical code, albeit varying from culture to culture. Most of us were brought up by our parents to know right from wrong and, as parents, try to instil the same in our children. We know that it takes children a while to know what they should and shouldn’t do, and many test the boundaries as they approach their teens. Those of us who have owned a dog also realise that we must train our pet to conduct itself in a manner we consider appropriate – come when called, sit when asked, refrain from barking in certain situations, and so forth. When it comes to wildlife, however, and particularly foxes in my experience, we seem to simply expect them to understand and conform to these rules.

We humans have a desire to understand things. A facet of the human condition is to ascribe meaning, which helps us cope with the uncertainty and variability of the world in which we live. Things are a lot less scary when you understand what’s happening; perhaps you could even predict or avoid some events. Centuries ago this was ascribing volcanic eruptions to angry gods, or weird lights in the sky to aliens. Even today many millions of people believe in a life after this one because it helps deal with the fear many of us have of death. So, when we come across a situation we don’t understand our brain tries to ascribe meaning, but in some cases we get it wrong. Predators are an excellent example of this because, by their very nature, they kill other animals to survive, and sometimes this behaviour can go into overdrive with results that we find disturbing.

Let’s say a fox goes after a rabbit. Its predatory behaviour is triggered by the sight of the prey; it sees, stalks, chases and kills the rabbit. By the time it manages to catch the rabbit, the rest of the colony has disappeared underground and the fox trots off with its prize. If a fox breaks into a chicken coop and grabs a bird the others have nowhere to go; all the squawking and flapping of the remaining panicked birds continually stimulates the fox’s predatory drive, until they’re all dead. (We know this to be the case because in situations where birds have remained calmly on their nests and the fox has been unable to get out, the fox and birds are found alive and well the following morning.) The fox can carry only one chicken at a time and that assumes it can get its prize back out the hole through which it entered. If it can’t it has no choice but to abandon the bird(s). If the fox can get in and out, I have testimony from several chicken keepers that the fox comes back over subsequent nights to remove the rest.

Unfortunately, the situation that an owner arrives to the following morning can only be described as carnage. To the human mind, brought up believing that killing is wrong and taking more than you need is selfish or greedy, surely there can be no explanation other than wanton bloodlust? It’s made worse because these are our pets, members of our family. It feels like a deliberate assault on us. It’s not, though. Foxes do what they’re programmed to do, without thought or concern for the feelings of their prey or the people who own it. They kill prey when they have the opportunity and, again given the opportunity, will take it and bury it for later use. The fact that we humans may not be able to get our heads around it doesn’t make it any less true.

Special pleading for the fox? Not really. It’s education. Twisting theories to match the evidence, rather than the facts to match theories, as Sherlock Holmes once "said". Managing expectations, as corporate management say.

I’ve seen foxes walk past rabbits and take a lamb mid-birth

This again assumes foxes should see animals owned by humans as somehow “off limits”. We expect foxes to hunt certain things, ideally things that don’t make us upset or uncomfortable, but, in the end, foxes are highly intelligent and adaptable predators that won’t pass up the chance of an easier meal if one presents itself. I suspect, if we stop and think, many of us are the same. In our house my girlfriend does most of the cooking. When she’s away, I subsist mainly on salad boxes and cereal because, frankly, I’m too lazy to cook when I get in from work. I doubt I’m the only one, either.

The fox population has exploded and needs to be controlled

This is one of many unknowns about the British fox population. Estimating the total population of any free-ranging animal species is a hugely complex task and prone to error. Consequently, few estimates exist and there are no regular monitoring programmes for foxes in the UK. It certainly seems like people are seeing foxes more often. The problem, however, is that we now know, based on the analysis published by Brighton University’s Dawn Scott and her colleagues in the journal PLOS One back in 2010, that there’s no correlation between sightings and density. In other words, seeing lots of foxes doesn’t mean there are necessarily lots of foxes around. This may sound like a counterintuitive notion, but visibility is based on how confident or retiring individual foxes are. Foxes can be difficult to individually identify, which means you may frequently see the same one or two animals around, but interpret this as there being lots of foxes.

The most recent studies of which I’m aware, again largely based on Dawn Scott’s work, suggest that the fox population has risen and, in particular, there are probably now about 150,000 foxes living in our towns and cities – a five-fold increase over the very rough estimate of 33,000 in the mid-90s. The data suggest, however, that it is not the density that has risen, but the distribution. In other words, there are more urban-dwelling foxes now because they’ve colonised more cities, while the number per square kilometre in southern cities (London, Brighton, Southampton, etc.) hasn’t changed. (I know some pest controllers dispute this, but I have seen no data in support of this.) In 2001 a survey attempted to establish which of Britain’s towns and cities had resident foxes. A follow up to this, conducted in 2012 as part of the Foxes Live series on Channel 4, found that 90% of the towns and cities that didn’t have foxes in 2001 reported them in 2012.

While foxes have been busy colonising Britain’s cities, particularly in the north, numbers appear to have been declining in the countryside. Data from the mammal monitoring contingent of the British Trust for Ornithology’s Breeding Bird Survey suggests an overall decline in fox numbers in England of about one-third between 1995 and 2015, with a particularly steep drop since 2010. Several factors may be at play here, including a decline in earthworms in response to pesticide use and the reduction in the rabbit population (down by about 60% in the same period), but Durham University zoologist Phil Stephens, quoted in an article in New Scientist during January 2017, suggested:

“… since the hunting with dogs ban came into force, gamekeepers have felt a particular obligation to hammer foxes as hard as they can.”

The most recent total figure for fox numbers in the UK of which I’m aware was calculated by biologists at the Animal and Plant Health Agency and due to be published by The Mammal Society later in 2017. Using published data collected between 1960 and 2013 to build a model on habitat density, they estimated that Britain may have as many as 430,515 foxes, although they note that “there is also uncertainty surrounding the estimate”. If this is accurate, that suggests the fox population has almost doubled in the last 20 years. The fact that most of this seems to be colonisation of new areas, however, casts doubt on claims of a "population explosion".

The Hunting Act is a bad piece of legislation

A friend of mine summed this up quite nicely in a Facebook post when he pointed out that this statement takes an argument of principle and makes it one of procedure. Does this mean people making this claim support the principle of banning fox hunting with hounds and would thus vote for a strengthening of the law? Instead, the answer to “bad” legislation seems to be to repeal it rather than improve it. In the end, there are undeniably issues with the Act. In particular, there is a fairly strong case for an amendment to allow a small pack of hounds to be used to flush foxes from plantations, where stalking is largely impossible owing to the terrain, to waiting marksmen (i.e. legalising the ‘foot packs’ that are permitted under Scottish law).

There is a further case for exemptions to be granted to allow multiple dogs to be used to flush deer and foxes from dense cover for the purposes of surveying. I have also heard reasonably compelling arguments for allowing stalkers to employ up to four dogs to track deer and foxes and to help with the recovery of any wounded animals. It is also worth remembering that the Act is not all about foxes; it also serves to regulate stag (red deer) hunting and hare coursing and it is important not to lose sight of this when deciding how the bill should be managed. Regardless of its short-comings, the Act is an attempt to update Britain’s animal welfare legislation to bring it into line with many other European countries.

Fears the bill would be largely unenforceable don't, however, seem wide of the mark. Up to the start of 2017, 24 (about 6%) of the 423 convictions under the Act related to registered hunts, with the remainder being for "casual hunting" infringements, such as poaching. According to the Countryside Alliance, these figures clearly show that the Hunting Act "lies in tatters", while saboteur groups are quick to point out that a significant factor in these statistics is that police seem largely uninterested in investigating complaints made against hunts. Enforcement is complicated by police being confused as to how to tell a drag hunt (which is legal) from a bona fide fox hunt and not having the resources to follow the hunt in order to keep tabs on their activities. The passing of the initial anti-hunting bill was certainly only the beginning of any attempt to curb so-called "blood sports" in Britain.

The Hunting Act hasn’t saved a single fox

This observation misses the point of the legislation. The Act was never intended to be a fox conservation act. Red foxes aren’t a conservation priority anywhere in the world and show no signs of becoming one. Instead, the Act was designed to regulate the way the animals could be killed. It was a statement that there is no need to set a pack of dogs on a fox when there are more humane and more efficient methods available to cull them; that tradition does not supersede animal welfare.

Hunting of wildlife will, I suspect, always be a highly contentious issue. Personally, I believe the key to be an appropriate level and method of hunting that’s based on evidence. I'm inclined to agree with King George VI, who said:

"The wildlife of today is not ours to dispose of as we please... We have it in trust and must account for it to those who come after."

Related Questions and Answers:

Q: Do foxes kill for fun?

Q: How can I keep foxes out of my garden?

Q: Is Surplus Killing and Caching a Waste?

Q: Is it likely that a fox will attack me, my family or my pets?

Q: Should we reintroduce large predators to control foxes?

Q: Should we be culling urban foxes?

Q: Are fox numbers increasing in Britain?

Q: Are foxes getting bolder?

Q: Are urban foxes getting bigger?