Summary

Fox “attacks”, usually minor bites, on people are extremely rare and, generally speaking, foxes are not a threat to humans. The number of attacks on cats and dogs each year is unknown, but seem to be of only minor significance relative to attacks on each other (i.e. dog on cat, or cat on cat). Typically foxes and cats ignore one another and fights are rarely observed.

The Details

The short answer is no. It is, as we shall see, certainly not unknown for foxes to attack cats and, more rarely, dogs or people; but none of these incidents are likely. I must say from the start that I understand and appreciate that this is a sensitive subject and that all the statistics in the world offer no consolation to someone who has lost a beloved family pet to a fox; nor to anyone who has been injured, or whose child has been injured, by a fox. I feel, however, that it is important maintain a sense of perspective and to understand that the fact such events do happen, does not mean that they are common occurrences. That which follows is a summary of the information currently available regarding the occurrence of fox attacks on people, cats and dogs.

In recent years, following the case of two young twins who were bitten by a fox in London during 2010, the UK has seen something of a media 'frenzy' over urban foxes and the danger they pose to people and their pets. The apparently unprovoked attack on the girls left experts confounded and many people afraid of the animals with which they share their streets and gardens. Some newspapers have been quoting local pest control companies who say urban fox numbers are on the rise and they're seeing more problems than ever before.

Fox numbers appear to have risen in recent years, and a recent estimate from Brighton University biologist Dawn Scott suggests there may be as many as 150,000 in our towns and cities. Interestingly, however, Scott and her colleague Phil Baker at Reading University have found that there is no correlation between fox densities and sightings. In other words, seeing more foxes around doesn't necessarily mean that the population has risen. Similarly, there is currently no evidence that foxes are more of a nuisance or more dangerous now than at any point in the last decade.

When it comes to assessing the evidence, whether it be scientific or otherwise, we must be mindful that we can only observe a fox for a fraction of its time (often using radio-tracking, which only tells us about the animal's movements and generally nothing about what it's doing at the time) and over a fraction of its range. Moreover, each fox is an individual: some are bold, some shy, some reclusive, some tenacious. We must thus be careful when generalizing; applying what we observe in one situation to all situations may over- or underestimate the risk. Naturalist and writer Brian Vezey-Fitzgerald summed it up nicely in his 1942 book A Country Chronicle, in which he wrote:

"Dogmatism in any branch of natural history is not only foolish, it is a sin."

I am keen to emphasise that this is not a case of "special pleading" on behalf of the fox, and I am not suggesting that foxes are blameless. I am simply keen that our opinions and actions are based on a rational and balanced appraisal of all the evidence.

Fox attacks on people

Outside of the UK, especially in parts of Europe, India and America where foxes are a vector for rabies, attacks are reasonably well known, but still far from commonplace. In Britain, they are even more infrequently reported and, until recently, received little widespread media attention.

Concerns about urban foxes were probably first voiced by the media in an article about "vulpicide" in the London town of Orpington that appeared in The Sunday Times on 17th June 1973. The article told how Bromley Council, the borough in which Orpington sits, had employed a full-time fox-control officer who was responsible for shooting and gassing foxes in the area; apparently, this was in response to a small child having been attacked by a fox. It seems, according to this article, that the "attack" actually took the form of a young boy who said a fox jumped up at him in an outside toilet at the Battle of Britain air show. The article contained excerpts from Bromley Council minutes warning of the threat that urban foxes posed to people and their pets.

Similar articles crop up from time-to-time and many carry a quote from a source who says 'it is only a matter of time before someone is seriously injured by an urban fox'. Unfortunately, despite their unequivocal rarity, especially considering the estimated number of foxes and their proximity to people in towns and cities, several incidents have been recorded, although the validity of some accounts has been questioned.

The next case of which I am aware made the press, in The Independent, just over two decades after the original Sunday Times article. In early November 1996, five-month-old Philip Sheppard needed hospital treatment for an injury to his face after apparently being bitten or scratched by a fox while lying in a pram in his parents' conservatory in south London. According to the media report, his mother came out to investigate his cries and found the fox on top of him. The paper quoted various fox experts, all of whom were astounded by the attack and some who questioned the culprit, suggesting that the wounds were more reminiscent of having been scratched by a cat.

In response to this story, Bristol University ecologist Stephen Harris wrote a short article to Country Life magazine later that month in which he described the hysteria that followed the attack as a "misinformed overreaction". Professor Harris explained:

"The fox did not attack the baby and made no attempt to bite it; at worse, it was slightly too inquisitive."

The title of Professor Harris' article, "Foxes pose no threat in cities", summed up his opinion (and remains the opinion of many fox biologists) on the matter.

In late June 2002, there was a report of a fox biting a 14-month-old boy who was asleep in the lounge of a house in Dartford, Kent and, on 9th September 2003, The Sun carried the story of four-year-old Jessica Brown who was, according to the paper, "mauled by a starving fox" while lying in her bed -- the accompanying photo showed a u-shaped bite and localised bruising on Jessica's left arm.

Following several reports of foxes apparently killing pets in Edinburgh, an article appeared in The Scotsman newspaper when a local pensioner was bitten. In August 2004, Margaret O'Shaughnessy was bitten on her left ankle by a fox while putting out milk for her cat in her garden in the Firrhill area of the city. Additionally, January 2007 saw the case of two paperboys who found a two-year-old baby boy crawling down a street in Croydon, South London at 6 am being followed by a fox. According to an article in The Sun, the boys had to "kick away a snarling fox before picking up the tot". I should mention that there is nothing in the article to suggest that the fox in any way harmed the baby and one is tempted to think the animal was following the baby out of curiosity.

The Koupparis twins

The incident that most will be familiar with is the widely publicised case of two young girls who were bitten by a fox in a London suburb. In a terraced house in Hackney, Greater London, just before 10pm on 5th June 2010, Pauline Koupparis went upstairs to investigate the crying of her nine-month-old twins Lola and Isabella; she found them in their cots, bleeding from deep wounds to their upper body apparently inflicted by a fox that was still in the room. Mrs Koupparis called for her husband and together they tried to remove the 'medium-sized' fox, which was apparently unfazed by their lunges. Eventually they managed to chase the animal downstairs and out into the garden. The children were rushed to the Royal London Children's Hospital, where they were treated for severe soft tissue injuries. Isabella suffered a severe bite to her left arm, while Lola sustained a minor bite to her right arm and a serious bite just above her right eye.

This story attracted much media attention and was broadcast around the world; various fox experts expressed their surprise at the incident and some questioned whether a pet cat or dog that was actually to blame. In the documentary on the incident broadcast by the BBC, the Koupparis family reiterated that it was most definitely a fox and explained that they do not have any pets.

Despite some rather disturbing, and at times frankly appalling, abuse the family received from some members of the public, the police investigated thoroughly and, based on the wounds and expert testimony, were satisfied that the twins were bitten by a fox. This attack raised many questions about urban foxes -- about whether they were getting bolder, more numerous, or hungrier; in short, whether they are more dangerous now -- and caused much speculation as to the reason behind the animal's behaviour, including that it might have been a cub or suffering from toxoplasmosis.

This case is quite remarkable because not only did the fox enter the house (that can perhaps be explained by the remains of a barbeque left cooling in the kitchen), but it also went upstairs and seemed quite "at home". It has been suggested that the fox may have been attracted upstairs by the smell of the nappies, such items occasionally having been found at earths, but this is purely speculative and, writing in British Wildlife in February 2020, something that Stephen Harris considered highly dubious, given what we know about fox biology. Why it bit Isabella and Lola we will never know, but some have implied that it shouldn't be a surprise given that 'a young baby isn't much bigger than a lamb or piglet'.

I do not wish to detract from the fact that this was a serious incident, terrifying for all those involved, so I won't address this more than to make the point that, even if this were an accurate comparison, cases of foxes taking lambs and piglets, especially live ones, are uncommon. The bulk of a fox's diet is composed of much smaller prey, namely invertebrates (especially earthworms), rodents, birds and rabbits. For reference, lambs and piglets are most vulnerable within the first couple of weeks after birth when, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization, they weigh about 2kg (3 lbs 3 oz.) and 1.5kg (4 lbs 6 oz.), respectively. According to the World Health Authority, a nine-month-old girl weighs in the region of 10kg (22 lbs), about the same as an adult fox.

Why the fox wandered around the house might be alluded to by Mr Koupparis' comment in the documentary that it "sat at the top of the stairs like a family pet". I have seen many videos showing foxes being enticed into houses by people offering food, and readers have sent me photos of foxes lying by their fireplace or standing in their kitchen waiting for food. Equally, I have seen people strike up that "special relationship" in which the fox feels secure enough to take food from their hand and those who have awoken to find a fox asleep on their bed. It seems that some people see urban foxes as a 'free pet', forgetting that they are actually wild predators.

Feeding the problem

It is frequently stated that feeding foxes is a bad idea because it causes them to become dependent on the food being offered and teaches them to associated people with food. Personally, I don't believe this gives foxes the credit they deserve for being highly intelligent and adaptable animals. To the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence to suggest that feeding foxes leads to dependency; nor that foxes view all people the same. Indeed, my personal experience is that foxes learn to trust the food-giver and continue to treat others, even those accompanying the feeder, with great suspicion. Consequently, I personally do not see a problem feeding foxes, provided it is done responsibly.

First and foremost, this means that only a small amount of appropriate food should be put down. A couple of handfuls of dog biscuits or peanuts sprinkled on the ground is sufficient to delay a fox long enough to get some decent views and photos. The issues associated with over-feeding (increased local disturbance, higher fox densities, etc.) are well documented. Similarly, foxes should not be fed chocolate, cakes or other high sugar, high fat, processed foods. In addition, never encourage the fox to take food from your hand and never entice them into your house. I know several people who do both and have never had an issue; but in my opinion it is courting trouble. Foxes are opportunists and, while some are likely to be more prone to enter a house from the outset looking for a meal, others may make the mental link that houses are good places to look for food if some well-meaning human sows the seed, so to speak.

In the case of the Koupparis attack, someone in the neighbourhood encouraging local foxes into their house for food may have contributed to the incident. Foxes are perfectly capable of distinguish regular human 'watchers' from newcomers and can almost certainly tell one house from another (i.e. entering the wrong house by mistake seems unlikely), but if a fox has found that one house yields food, it makes sense that another might also.

Post Koupparis incidents

Shortly after the Koupparis incident, thirteen-year-old Bethany Blackburn was bitten on her left foot by a fox that, according to media reports, tore a hole in the tent in which she was camping with two friends just before midnight on Sunday 25th July. According to one report, the fox spent two hours scratching at the side of the tent, before it got in. An article in The Daily Mail told how the fox:

"... sat, snarling, in the porch area, only turning tail when Bethany's mother, who the desperate schoolgirl had alerted on her mobile phone, switched on the kitchen light and came out to investigate."

This incident happened in the Blackburn's back garden in a suburban part of Long Ditton, Surrey. Miss Blackburn told the paper that the fox, which the girls said was a cub, returned to the garden the next night and urinated on the tent door. There was apparently no food around at the time, so it was presumably curiosity that attracted the fox to the tent. Snarling is most certainly an abnormal behaviour and not one that I have ever seen, nor seen any experienced fox-watcher mention. Indeed, some zoologists point out that foxes do not snarl and suggest the account was exaggerated, although we cannot say for sure. The marking behaviour is not unusual, however; foxes very often scent-mark novel objects in their territory, and a tent would certainly fit the bill.

Since these incidents a couple more have made the press. In September 2010 Annie Bradwell was bitten on the ear by a fox while in bed in her house in Fulham, West London, and in the early hours of Sunday 24th October 2010, a 37-year-old man was found unconscious by police in St Michael's Parish Church Cemetery in Musselburgh, Scotland, suffering from hand and facial injuries thought to have been caused by an animal. There is no direct evidence linking the injuries to a fox, but a local councillor was quoted by the BBC as saying: "I stay not far from that area and the only animals around capable of doing such a thing are foxes."

In January 2011, Tammy Page was bitten on her left index finger while trying to expel a fox from her kitchen and, later the same month, Deborah Adams was bitten on her left arm when she tried to touch a fox she found sitting in the road to Gluvian Farm in Cornwall. In February 2013, five-week-old Dennie Dolan bitten by a fox in first floor flat in Bromley and, in July of the same year, Anthony Schofield called 999 after sustaining a fractured wrist and two bite wounds while trying to prevent a "mangy little fox" attacking his cat in his living room in Catford, South London. The most recent incident I'm aware of in the UK was that of a two-year-old boy who was apparently bitten on the foot by a fox that entered a house in New Addington, south London, via a cat flap in November 2014. The parents found the fox sitting at the end of the toddler's bed.

These are, of course, the cases that have made the mainstream press, and one wonders how many go un-reported. I, for example, know of at least one attack, recounted on an Internet message board, that was alleged to have happened in August 2005. A gentleman in south-east England was apparently charged by a fox that "ran the length of the garden squealing" and bit his leg. So engrossed in this activity was the fox that it ignored being kicked by the man and blasted with a hose by his wife; it only fled when the couple's huskies were let out. This incident was reported to his local Council, but it doesn't appear that any formal investigation was carried out. Similarly, a man in Flevoland in the Netherlands filmed a fox pacing outside his chicken coop on his mobile phone in August 2015. When the fox spotted the man, it turned and ran at him, causing the guy to turn and run. The video went viral, but doesn't appear to have made the UK press.

A drop in the ocean?

According to a pest control officer interviewed about the Koupparis attack on the The Fox Attack Twins BBC documentary in 2010, cases of foxes biting people are now common in Britain, but many people don't report them, presumably for fear of not being believed and potentially suffering abuse. This situation is no doubt exacerbated because Britain, unlike most states in the USA for example, does not have a statutory body to whom bites can be reported and that keep track of cases. The Health Protection Agency's (HPA) Zoonoses Department recommend reporting any bites/attacks to your Local Authority's Pest Control Department, even though they will probably be unable to aid in the removal of the fox. The HPA also advise anyone bitten by an animal (wild or domestic) to seek medical attention as soon as possible. It seems inevitable that some bites will go un-reported, but a lack of official reporting in Britain ultimately hampers our ability to assess the risks posed by foxes.

Foxes are medium-sized carnivores and this alone means they have the potential to be dangerous, just as a pet cat or dog does. This capacity does not, however, mean that foxes pose a significant threat to people. Foxes probably are bolder now than they were when they first colonised our towns and cities back in the 1930s and 1940s (see QA), but I feel it's important to recognise that boldness is not synonymic with viciousness. Bites happen from time to time, but such incidents are still extremely rare.

I will spare you the statistical comparisons with dog and cat bites, because I don't feel they are particularly relevant, and just reiterate that it's important to be as cautious and sensible around foxes as you would any wild animal. Take common sense precautions and, unless you are familiar with the animal(s) in question, do not approach, or let your children approach, foxes that come into your garden. If you wish to take steps to exclude foxes from your property or deter fouling in your garden, there is advice on the Fox Deterrence page of this site.

Foxes and domestic dogs

It is often considered that domestic dogs are one of few pets that a fox will not attack and this seems to be largely supported by the evidence. Indeed, I am only aware of one confirmed record of a dog having been killed by a fox. One morning in July 2010 a two-year-old Chihuahua was attacked by a fox that was apparently lying in long grass in a garden in Poole, Dorset. The owner of the dog chased the fox into a neighbouring garden and managed to retrieve the body of his pet after what, in an interview with The Daily Mail, he described as "a bit of a tug"; but unfortunately the dog was dead, having suffered a broken neck.

This is a curious case because it bares the hallmarks of a predatory attack. The fox appears to have attacked the dog before carrying it away, presumably with a view to eating it. This case is exceptional; it may even be unique. There was an unconfirmed report several years ago involving a fox, which turned out to be a neighbour's pet, attacking a Staffordshire terrier-cross and another, in August 2012, during which a fox apparently jumped from some bushes and bit the muzzle of a greyhound. In the latter case, the owner reported that the fox "grabbed [the dog] round the jaw and was hanging off him" before the greyhound broke free and killed the fox.

Despite occasional reports of foxes attacking dogs, typically small breeds, in most cases it is the dog that attacks the fox and dogs may be a limiting factor in urban fox distribution. In a paper to the Journal of Applied Ecology during 1981, Stephen Harris estimated the number of foxes in Bristol city and assessed some of the factors affecting their distribution. Harris collated 4,894 records of stray dogs (3,012) and cats (1,882) from Bristol Dogs Home, mapped them against records of fox presence and found that the concentration of stray dogs (but not cats) explained fox distribution in parts of the city. Harris wrote:

"This study suggests that a major factor affecting the distribution of foxes in Bristol is the presence, in certain areas, of large numbers of stray dogs."

Indeed, Professor Harris found that stray dogs commonly disturbed and chased foxes. Moreover, during the study 87 dead cubs were recovered from the city, 13 (15%) of these were found to have been killed by animals and, in most cases, dogs were responsible. According to the most recent survey by The Dogs Trust, published in 2021, local authorities in the UK handled 49,292 stray dogs between April 2019 and March 2020, suggesting stray dogs are still a considerable problem in Britain.

If we consider that most foxes are about the size of a large domestic cat, they probably pose a potential threat to only the smallest breeds. In my experience, foxes are wary of dogs, certainly of medium to large breeds, but there have been some reports of unperturbed foxes "intimidating" people out walking their dogs; these reports are often dismissed by researchers, but I have received several accounts of such instances and feel they warrant mention. In one account a lady reported being followed by a fox while out walking her dog at night until she crossed a road (presumably a boundary of the territory) at which point the fox turned and left.

Another example was that of a lady in London who told me she was repeatedly barked at and followed by a fox while out walking her Belgian Shepherd dog at about 11pm in June 2010. In these cases, and a couple of others readers have contacted me about, the dog appears the focus of the fox's attention and, based on the descriptions of the foxes' behaviour, it seems probable that they were anxious at the dogs' presence. Nonetheless, in February 2007, a lady wrote to me describing how a fox followed her while out walking her Welsh terrier in Surrey and, when she stopped, it approached and started play bowing to her dog.

Indeed, not all fox-dog encounters are irascible and I have come across accounts of dogs playing with foxes. In May 2007, the BBC Wildlife Magazine published a supplemental booklet called Fox UK, which contained information about foxes (compiled by Professor Harris) along with photos and stories sent in by readers. In one letter, Mike Squires told how his 15-year-old Border Collie spent several minutes playing with a fox in their garden in Wales one December morning, with each taking it in turns to chase the other.

In his 1986 book, A Fox's Tale, Robin Page described how a fox cub he raised would play with the farm kittens and their black labrador. Similarly, Michael Chambers, in his 1990 book Free Spirit, described how a vixen he raised from a cub formed a strong bond with his dogs, even allowing one to babysit her cubs. In Town Fox, Country Fox Brian Vezey-Fitzgerald recounted examples of foxes playing with dogs in his neighbours' gardens, in one case with a Dachshund and in the other a miniature poodle, although he points out that in his experience foxes generally avoid dogs:

"The fox avoids dogs rather than ignores them. I do not think there is any question of fear involved. Certainly I have seen no sign of fear. And I think that the fox is not an easily frightened animal. Avoidance is merely an elementary precaution."

Foxes and domestic cats

Whether or not foxes pose a danger to domestic cats is a question that has ignited debate for decades. The subject has made headlines in recent years, partly because there have been rumours that attacks are now more likely than ever before as a result of the Hunting Act of 2004 and many councils have implemented wheelie bins. The argument generally goes that the abolition of hunting with hounds has led to an increase in the fox population and that attacks on cats are the direct result; mounted hunts should, they argue, brought back. These subjects are covered at depth elsewhere on this site, so I won't dwell more than to reiterate that there is no evidence that: a) fox numbers have risen in response to the Hunting Act; b) mounted hunts have any impact on fox numbers; c) the introduction of wheelie bins has had any impact on fox diet, distribution or behaviour.

In February 2005, the Daily Telegraph carried the headline "Hungry foxes start eating the nation's cats" and the accompanying article told how fox attacks on cats were on the increase and quoted a pest controller near Edinburgh who explained that the fox population has gotten out of hand because the introduction of wheelie bins has deprived foxes of their regular food supply. As we have discussed already, there is no evidence of this, so if the number of fox attacks on cats has increased (or is increasing) it seems the reason lies elsewhere.

There are few data sets to tell us how many cats are attacked by foxes each year, not least because positively identifying the culprit as a fox (as opposed to a small dog, for example) is difficult. Probably the most off-cited statistics on the subject come from Bristol University. Stephen Harris distributed 5,480 questionnaires asking about fox disturbance, including losses of pets to houses in an area of north-west Bristol estimated to be home to 1,225 pet cats. Harris received 5,191 (95%) completed surveys and calculated that eight (less than 1%) of these pet cats, most being kittens less than eight months old, were thought to have been killed by foxes.

The problem with the Bristol data is that they are not recent; it first appeared in a paper by Harris on the food of suburban foxes published in the journal Mammal Review during 1981 and the questionnaire was actually circulated in October 1977. When we consider that, in a 1986 paper to the Journal of Animal Ecology about urban foxes in Britain, Harris and Jeremy Rayner noted that the "colonization of London by foxes is continuing" and that subsequent studies in Bristol showed how the urban fox population peaked during the early 1990s, it is unclear how relevant these fox-cat statistics are today, 40 years on. A similar, questionnaire-based, study in Oxford conducted by David Macdonald at the city's university during the early 1980s yielded similar results to the Bristol survey -- in this case, nine of the 6,143 respondents believed their cat had been killed by a fox.

The most recent reference I'm aware of was a blog post that veterinary surgeon Pete Wedderburn made on VetHelpDirect in February 2013. Wedderburn searched the VetCompass data base for records of cats admitted with injuries caused by a fox. The database holds medical records for some 400,000 pets from 200 practices across the UK, 145,808 of which are for cats. Wedderburn's search returned yielded 209 admissions, 79 confirmed and 130 suspected fox fights, between January 2010 and February 2013. These results suggested 14 in 10,000 cats were attacked, or believed to have been attacked by foxes over this period, an incidence of 0.14%. When Wedderburn ran the same search for cats admitted having suffered different injuries, he found cats were 40-times more likely to be bitten by another cat and 14-times more likely to be hit by a car than attacked by a fox.

Dietary studies and observations of dead cats recovered from fox earths suggest higher occurrence in urban than rural areas. Indeed, most rural studies make no mention of cat remains in either fox scats or stomach contents, although during his 1981 review Harris found cat remains in 2.1% of stomachs he studied, while a similar study on the food ecology of foxes in Sweden, conducted by Jan Englund during 1965, found cat remains in just under 2% of stomachs. Macdonald's studies found lower levels, with cat fur in eight (0.4%) of the 1,939 scats they collected. The problem with making inferences based on remains is that the foxes could've scavenged the remains. I know of no recent figures, but in November 2006 the insurer Petplan estimated that some 230,000 cats were run over in Britain every year, an average of 680 per day, with Bristol topping the blackspot list. Given that foxes are well known to scavenge roadkill, it seems this habit may explain the presence of cat remains in their diet.

There can be no argument that foxes can and do kill cats. They don't appear to do so often and are only thought to represent a minor threat to pet cats. In his entertaining and well-written account of urban foxes, published in the October 1985 issue of the BBC Wildlife Magazine, David Macdonald pointed out:

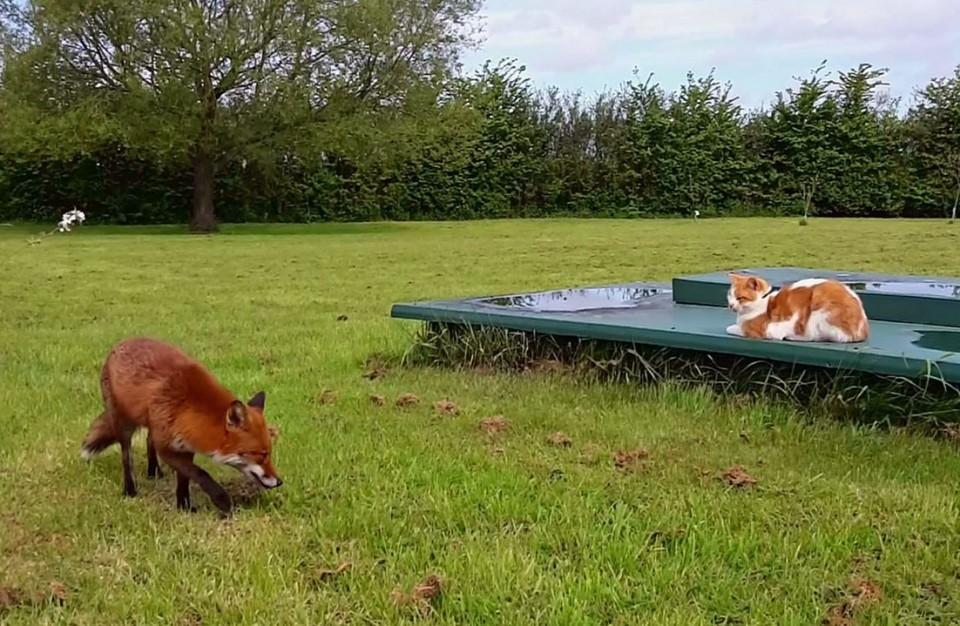

"... both species are numerous in towns and active nightly in the same gardens, where they meet continually. If foxes in general were a serious threat to cats the losses would be huge."

Both species are, indeed, numerous. With an estimated 430,000 foxes in Britain and the Pet Food Manufacturers Association's estimate of 7.5 million pet cats in the UK in 2016, there are about 17 cats for every fox. Macdonald went on to describe how stalking with infrared binoculars in Oxford allowed them to watch fox-cat interactions on many occasions; most cases involved the two ignoring each other, but where conflict was seen the fox was apparently the more nervous of the two. A similar position was taken by Stephen Harris and Phil Baker in their 2001 book, Urban Foxes, in which they noted how foxes must meet many cats on their nightly forays and, in the Fox UK booklet, Harris wrote:

"As for cats - well, I have witnessed many encounters between foxes and cats. The cats win every time, since the foxes are reluctant to risk injury when faced with such a powerful foe."

Probably the biggest hurdle to assessing fox-cat interactions is that both species are nocturnal, which means that encounters are rarely observed and the first the owner knows of the confrontation is when they find the body the following morning. This leads to a certain amount of conjecture, not least because it can be very difficult, sometimes impossible, to separate the wounds made by a fox from those made by dog.

It is often assumed that a fox is responsible because one (or several) has been seen in the area and no dogs have ever been seen in the garden, but we've had 'foreign' dogs in our garden without their neighbours' knowledge and, as we've seen, there is a significant stray dog population in Britain. There have been several incidents where a fox was believed to have killed a cat that have made the papers and most follow the same line: residents are woken by what they describe as a cat fight and, in some cases, a fox is seen at some point during the night. Recently, I came across the case of a veterinary nurse from Manchester who regularly has foxes visiting her garden that emphasizes the difficulty in being sure. The following is parts of her original account, reproduced here with her permission:

"At 8.00 this morning [23rd January 2011], we let our cat out (he is a lazy, diabetic cat, with no interest in birds or other wildlife. He lives for his meal times and does not venture out of our garden, so does not leave his business in other gardens). I went upstairs and at 8.30 my daughter came up screaming that he was being attacked by 2 dogs in our garden. We ran downstairs to find 2 terrier type dogs - one had him by the throat, the other by the back legs. When I ran out, they tried to carry him off, but I managed to get him.

I am lucky that I was able to assess his condition until I could take him to the vets where I work (we are not open on Sunday, so I had to get the vet up, for which I am eternally grateful). He is now on a drip, with IV antibiotics and pain relief. He has been lucky - in the respect that I was able to take him away from the dogs before they tore him apart - which they would quite literally have done. One of his hind legs is very badly injured, and will be x-rayed tomorrow. It looks badly broken, and to be honest I expect the eventual outcome will be amputation. He is also concussed, he was thrown to the ground with such force. To get back to the point - if we hadn't caught the dogs in the act, we would have found pieces of our cat strewn around the garden and assumed that the 2 foxes we watched in our garden the other night were responsible."

More recently, in February 2018, rumours surfaced that a cat had been attacked and killed by a fox in the Honicknowle area of Plymouth. The body was recovered by a member of Plymouth UK Pets Lost and Found (PUKPLAF) and taken to a local veterinary practice for assessment. According to a social media post by the Plymouth & SW Devon branch of the RSPCA, the autopsy revealed that the cat had been hit by a car and did not find any injuries consistent with a fox attack.

I'm only aware of a couple of accounts where the attack has been witnessed. In late August 2003, there was an incident in which six foxes were apparently seen attacking a 12-year-old tortoiseshell cat in a back garden of a house in Corstorphine, Edinburgh. One of the cat's owners managed to scare the foxes away and rushed her pet to the vet -- unfortunately its wounds were too severe and it had to be euthanized. This case is unique because it involved several foxes and foxes are solitary hunters; they do not hunt in packs. So how might we account for this bizarre observation? Parent foxes teach their cubs how and where to hunt and cubs may accompany them on hunting trips. If the incident took place as published, this was presumably a family with well-grown cubs (almost indistinguishable from the adults) accompanying their parents on a hunting trip.

Another incident happened more recently, in August 2010, and involved a fox entering a house in Folkstone, Kent through an upstairs window and attacking an eight-week-old kitten. As with the 2003 incident, the owner intervened and caused the fox to drop the cat and flee, but the kitten had to be euthanized several days later. This is the first case of a fox entering a house and attacking a cat, raising the question of whether someone locally had been feeding it in their house prior to this. The final example I plan to include is one e-mailed to me by a lady in Hampshire who, in the early hours of the morning of 23rd January 2011, witnessed a fox dragging a cat outside their house; part of her e-mail is reproduced here, with her permission:

"At about 3.30 in the morning I was awaken by a kind of strangled cat wail. I live in a surburban area with flats opposite and we often have cats fights so running to the window (we have a very large cat who often fights!) we were very shocked to see a medium size fox dragging a struggling cat by the scruff of the neck infront of the flats - about 15 metres, stopping to readjust and then across the road towards our house. At that point (another 10 metres) my friend made a loud hissing noise not knowing what else to do and this startled the fox which dropped the cat. The cat immediately ran very fast away while the fox looked up and then started walking past our house (opposite direction from where it had been running with the cat), looking at the house then glancing back towards where the cat had run. The fox was just walking slowly and calmly away. It was not our cat, but it was a medium size cat, not small or 'kitten looking' and it ran away very fast."

If we see a fox attack a cat, that's one thing, but how can we be sure that the cat was killed by a fox if we didn't witness the incident? Well, there are some features that tend to be associated with fox attacks, rather than dog attacks or fights with other cats -- they do not, however, offer conclusive proof. It has been suggested that intercanine distance (i.e. the size of the gap between the canine teeth) can be used to identify the culprit, but foxes and medium-sized dogs have similar distances; about 30mm and 26mm for their upper and lower canines, respectively. Indeed, in a paper to the journal Wildlife Research during 1970, Ian Rowley presented the results of his five-year study on lambing flock mortality in south-east Australia and wrote of:

"... the impossibility of differentiating between fox and dog attack on the basis of the wound inflicted .."

Nonetheless, decapitation and the smell of fox on the body are both strongly associated with cats killed by foxes. In his Town Fox, Country Fox book Brian Vezey-Fitzgerald described two instances where one of his cats appeared to have been in a fight with a fox and, on the first occasion, he noted how the cat smelt strongly of fox; several readers have contacted me saying much the same. Why, though, would a fox attack a cat? Why attack something that's about the same size as you, with sharp claws and teeth?

Foxes may see cats as a potential meal, and I have seen it suggested that certain foxes may be more prone to attacking cats than other -- some may "specialise" in cats, was how one author described the situation. This might explain local "blips", where several cases are reported in the same town in a short period, but generally superpredation (where one carnivoran eats another) is rare; carnivores often carry parasites and, cats in particular, have a rather unique protein metabolism that makes their meat greasy. More recently, in his article to British Wildlife in 2020, Stephen Harris noted that foxes have nothing to gain and a lot to lose from fighting with a cat and even dead cats aren't high on the menu:

"Even though some 230,000 cats are run over each year (an easy food source), Foxes eat very few of them. As a very rough estimate, I calculated that only around one in 500 road-killed cats is scavenged by a Fox. It is common to see a Fox sniff a dead cat and pass on. Cats are not a favoured food item and, presumably, eaten only if a Fox is particularly hungry."

Nonetheless, in November 2011 I received an e-mail from a gentleman living at the foothills of the Wicklow mountains in Ireland who found a freshly-killed kitten buried head first in a raised vegetable plot in his garden. Assuming a fox was responsible, and the details in his e-mail certainly implied so, burial of the kitten suggests it was being cached with the intention of eating later. Similarly, the conclusion of the Metropolitan Police's "Croydon Cat Killer" investigation was, unsurprisingly, that foxes were the culprits and, in their blog summary published in September 2018, they described three instances of foxes carrying cat bodies or parts thereof, particularly heads, captured on CCTV.

The most likely explanation for aggressive interactions seems to me to be that foxes see cats, and for that matter cats see foxes, as both competition for food and possibly a danger to their young (there are reports of cats killing fox cubs). It is not difficult to see how two equally-sized carnivorans setting up territories in the same area and hunting for the same food could lead to conflict. Consequently, such attacks may represent what biologists refer to as competitive displacement -- one animal kills another to remove competition for a resource. Certainly, there are reports from farmers that rural foxes are often particularly hostile towards farm and feral cats. Competition for food may be higher in rural areas, despite both cat and fox density being lower.

As with encounters with dogs, a fox and cat meeting is not likely to end in violence. I have come across numerous video and first-hand accounts of foxes and cats ignoring one another, feeding amicably from the same bowl and cats (even kittens) chasing foxes away. This broadly tallies with Harris' observations that of the thousands of fox-cat interactions he's witnessed, the cat won each time and, provided it wasn't cornered, the fox fled. There are even reports of the two species playing and hunting together. One particularly interesting account I received from a lady in Worcestershire described a fox and cat meeting in her garden during October 2014. The pair approached each other to within about a metre and the fox sneezed, or made sneezing actions towards the cat. The lady told me:

"The fox appeared to be sneezing, like a human would. He did this about 8 times before the cat walked away. Later the same evening they met again & seemed to be enjoying each other's company. The fox was jumping up onto a small brick wall then jumping down again close to the cat. Good entertainment for us."

So, if you're concerned about the risk foxes pose to your cat, what can you do? There are steps you can take to exclude foxes from your garden, but it is unlikely that your cat restricts its nightly wanderings to your garden alone. Given that both species are nocturnal, and that there is no guaranteed method of controlling the movement of either species, the most effective way to protect your cat is to keep it in at night, thereby vastly reducing the likelihood that it will meet a fox. This is also likely to reduce the probability that it will fight with any other cats, or dogs, and should reduce its impact on the local wildlife population. Additionally, keeping your cat(s) in at night also reduces the likelihood of it being involved in traffic accidents at times when there are few people around to see/help and veterinary assistance is more difficult to find.

In conclusion...

Ultimately, it cannot be denied that foxes do attack cats, dogs and even bite people on occasion. None of these are common and, while I appreciate that people who have lost their cat or dog to a fox, or been bitten by one will probably disagree, I do not believe that the current evidence supports the suggestion that foxes pose a significant risk to people, their cats or their dogs.

I feel there is a considerable need for more research on the subject of fox-cat and fox-human interactions in order to quantify the risk. I feel as our cities continue to expand, the conflict between humans and wildlife is inevitably going to increase. Eradication of foxes from urban settings is impractical and, for many people, unacceptable; so a change of attitude is required. Elsewhere in the world, people share their towns and cities with much larger carnivores than we have here in Britain, but a common sense attitude prevails and problems are surprisingly rare.