Summary

There is no simple or straight forward answer to this question because there is no regular census of fox populations anywhere in the world. Furthermore, the fox population is not uniformly distributed or responsive across Britain; so populations in some areas may be higher than those in others. Current informal (unpublished) estimates from The Mammal Society and the Animal and Plant Health Authority suggest that the stable (i.e. pre-cubbing) British fox population is around 430,000 animals, while a recent analysis from Brighton University suggests about 150,000 these live in towns and cities.

Foxes are more or less resident in every city in the UK now, although in recent years densities (foxes living in a given area) have increased in the north but remained stable in the south. Assuming these to be representative, this implies that the number of foxes has roughly doubled in the 17 years since the last attempt to estimate the national population. These figures also suggest that the urban fox population is about 4.5x larger than it was guestimated to be in the early 1990s.

Contrary to popular misconception, there is no evidence that fox populations have “exploded since the ban”. Indeed, there are no data to suggest that the 2004 Hunting Act (which made it illegal to hunt foxes on horse-back with dogs) has had any significant impact on national fox numbers and circumstantial evidence suggests that any ‘slack’ left in the wake of the hunt was taken up by gamekeepers and farmers shooting more foxes.

The Details

Monitoring animal populations, especially species that tend to be nocturnal and rather secretive is a difficult task and, until relatively recently, there had been no attempt to census fox populations at the national level.

Methods of assessment

So, what’s the problem with trying to count foxes? Many of us see them every day and in some cases they have become so accustomed to human presence that, even in relatively busy locations, they can be seen out during the daytime. Surely simply counting them shouldn’t be too much of a challenge? Well, as the former M.A.F.F. biologist Huw Gwyn Lloyd pointed out in his 1980 book, The Red Fox, it’s actually more difficult than it may first appear because:

“numbers are low and its ranges large by comparison with those of voles, rabbits or hares, for example. Inevitably, therefore, the counting of foxes involves a great deal of manpower and effort.”

Indeed, a count of all the individuals in an area, known as a direct census, is usually very expensive and largely impracticable, so we need to look at other methods; without a direct count, however, any method would only provide an estimate of numbers. Indirect censuses are often used and there are various techniques, including the mark-recapture studies and estimating the number in a given habitat and extrapolating up to a larger scale. These are, however, time consuming, often unreliable and may be limited by season so they coincide with the population being at its most sedentary. Commonly, indirect censuses involve attempting a count of all the animals in a small area and then use an understanding of the animal’s biology to extrapolate up to a larger area. Game-bags, the number of animals killed by gamekeepers, may sometimes be used in lieu of a census.

Game-bags are a convenient source of fox numbers and in the 1992 Game Conservancy Trust report, Game heritage, Stephen Tapper noted how game-bags for all ten regions of Britain showed a steady increase in the number of foxes killed per unit-area between 1960 and 1990, with the largest (seven-fold) increase being in south-east England and the smallest (two-fold) in Scotland. Unfortunately, the number of foxes killed by gamekeepers does not always reflect a true change in population density; numbers vary with effort, which is related to perceived threat to game. Consequently, more foxes killed do not necessarily equate to more foxes being around – it could equally be that culling efforts have intensified.

A third option is to use field signs and relate their frequency to the number of animals in the area – these are called population indices and are technically a form of indirect census. Population indices are among the most widely used methods of estimating animal populations, although they’re not without their problems. Indeed, in a 2004 paper to the journal Mammal Review, Linda Sadlier and colleagues at the University of Bristol assessed the use of field signs as a method of monitoring populations of Red foxes and European badgers (Meles meles). The biologists concluded that:

"At present, there is no single proven reliable method for monitoring changes in the absolute density of either foxes or badgers on a national scale..." and "...indirect methods [field signs such as scat and den counts] can only be used to measure relative changes in animal density in the same region over time."

Nonetheless, it has been widely demonstrated that the number of animals killed on roads, the number of tracks in an area, distribution of droppings in an area, spotlight counts et cetera can all be used to estimate numbers for various species, including foxes, at a local scale. Between 1969 and 1973 Steve Allen and Alan Sargeant even used the number of foxes spotted by postmen on their rounds to estimate the population size in six rural North Dakota towns. Foxes are arguably easier to apply these methods to than some other species, because they’re territorial and maintain fairly stable home ranges.

Counting fox droppings has been used to estimate the British fox population, although this can only really be applied to rural areas. In addition, the practice of counting breeding earths has been used successfully to estimate both rural and urban populations. The basic premise is that foxes live in family groups and raise a single litter of cubs per year. If one assumes a basic family unit (before the year’s cubs are born) is comprised of a dog, a vixen and a couple of subordinates (young from a previous year), it is possible to obtain a rough estimate of the number of foxes in the area based on how many family groups there are. Finally, we then divide the number of foxes by the size of our survey area to get the density.

This method sounds rather crude, but it is surprisingly effective and since its first application in Russia in 1941 it has been widely used. In May 1974, for example, Forestry Commission biologist Hugh Insley used a survey of breeding earths to estimate the fox population density in the New Forest in Hampshire. Insley used counts of 53 randomly selected squares and extrapolated up, based on the habitat, to arrive at a fox population of just under 600 animals, or a density of about two foxes per square-kilometre of Forest. Similarly, in the USA, biologists have used the technique to estimate fox numbers living on the plains. Despite being of local use, it is difficult to coordinate sufficient surveys to do this on a national scale, so an alternative approach is necessary. The first such approach involved using a system of classifying environments based on the type of habitats they include (called land class habitat mapping), developed by the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) in Cumbria during the mid-to-late 1970s.

Town fox, Country fox

In a paper to the Journal of Biogeography during 1981, Oxford University zoologist David MacDonald and ITE researchers Robert Bunce and Philip Bacon applied an understanding of fox behaviour and home range to data from habitat maps to estimate the home range of foxes across the country; from that they could calculate the density and estimate population of resident adult foxes in Britain during the spring. The biologists estimated population densities ranging from 0.23 and 2.25 foxes per square kilometre (basically, in a four sq-km area there would be between one and nine foxes, depending on the habitat) and calculated a total adult density of 252,000 foxes. As mentioned, this is an estimate of the spring population and the authors noted that the figures “could be more than doubled in late summer by the inclusion of juveniles”. This was an understandably rudimentary estimate of national fox numbers owing to the relative infancy of the land classifications. Indeed, at the time, there were many areas of Britain that hadn’t been assigned a land class and, perhaps more importantly, as Ray Hewson found when he applied the technique to fox populations in parts of Scotland five years later, it can yield a significant over-estimation of density.

In 1995 the Joint Nature Conservancy Council published A Review of British Mammals; a 183 page report co-authored by Stephen Harris, Pat Morris, Stephanie Wray and Derek Yalden that give details on the population trends of 64 species of mammal. In the Carnivora section, the mammologists used data on the number of barren (non-breeding) vixens and itinerant foxes (those without a territory) in an ‘average’ population, as well as data collected during Harris’ studies on urban fox densities during the mid-1980s (see below), to provide a more accurate estimate of the national fox population. Interestingly, despite introducing more factors into the calculations, their values were close to that of the 1981 appraisal. They estimated a total breeding population of about 240,000 animals; 195,000 in England, 23,000 in Scotland and 22,000 in Wales, with no estimate made for Ireland.

The authors pointed out that, assuming a mean litter of five cubs, each summer the population will swell to around 665,000, but the mortality rate is equivalent to the birth rate, meaning that the population is back to 240,000 by the following winter. This report also represents the first attempt at estimating the number of urban foxes, suggesting that about 33,000 of these foxes (about 14% of the total population) were living in towns and cities; 30,000 in England, 2,900 in Scotland and 100 in Wales. Subsequently, there were several attempts made to estimate rural fox abundance in various parts of Britain during the early 2000s, but no further estimates of the national population were published until the mid-2000s and no attempt was made to assess the urban situation until much more recently.

The next attempt to assess national fox numbers came in the form of a survey overseen by Bristol University biologists and carried-out by volunteers. Between 1st February and 17th March 1999 and 2000, volunteers were allocated areas across rural Britain; each site was visited and a pre-defined path walked, noting habitat characteristics and the locations of any fox droppings. The scats were then removed. A couple of weeks later the route was re-walked and scat positions marked again, but this time the faeces were collected and sent to Bristol for dietary analysis. In total 444 one kilometre squares from around mainland Britain were surveyed and, using food consumption and defecation rate information from captive foxes, it was possible to estimate fox numbers. The results of the survey were published in a 2004 paper to the Journal of Animal Ecology by Charlotte Webbon, Phil Baker and Steve Harris.

In congruence with the 1995 estimates, these new data agreed closely with the original 1981 figures. The data showed that the mean fox density varied from 0.21 to 2.23 foxes per sq-km, depending upon habitat, with some of the highest densities in western England and eastern Scotland. The result was a total rural fox population of 225,000; increasing to 258,000 when the 33,000 urban foxes estimated in 1995 was added.

In 2002, 160 of the squares were re-surveyed in order to assess whether the temporary ban on fox hunting that resulted from an outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease had any impact on fox numbers. The results, published in a report to the RSPCA and IFAW and in a paper to the journal Nature during 2002, showed a significant increase in the number of scats in eastern England and a significant decrease in southern England, with all other areas showing no change – overall, there was a decline in faecal density of some 5%. The conclusion of the report was that the ban on hunting had no effect on fox numbers in Britain.

In 2004 the Hunting Act was passed into law and concerns were raised that removing this source of fox control from the countryside could lead to an ‘explosion’ in fox numbers. In a bid to find out, just over half (252) of the original squares were re-surveyed, along with 139 new squares, during the winters of 2005 and 2006. The results, published in the National Fox Survey 2005/2006 Newsletter, were similar to those of the 2002 survey, with an increase in fox density in eastern England and a decline in southern England. Broadly-speaking, fox droppings increased in almost half the squares, and declined in the other half, with only 7% remaining unchanged. The conclusion of the Bristol biologists was that:

“At a national level, fox density was not different between the two surveys. Therefore, it appears that neither the Hunting Act nor sarcoptic mange have had an effect on fox populations in rural areas.”

In addition to the foregoing, there are a number of on-going surveys that have been recording the occurrence of foxes, as well as other mammals – these include the National Game-bag Census (NGC), Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), Waterways Breeding Bird Survey (WBBS), Winter Mammal Monitoring (WMM), Mammals on Roads (MoR) and Living with Mammals (LwM), although not all are still carried out. The latest (2015) data from the MoR and LwM surveys suggest that we're seeing about the same number of foxes killed on the roads and visiting our gardens now as we were back in the early 2000s, while the results of the 2015 BBS, which also counts mammals, suggests that fox abundance in the UK as a whole has actually declined by about one-third since 1996. This decline, the BTO suggest, may be associated with a decline in rabbits that has happened over the same time, although foxes have a very catholic diet and, with the exception of super-abundant food provided by humans, numbers are not readily affected by any single food source. In an article to the New Scientist in February 2017, Philip Stephens of Durham University noted that there is anecdotal evidence to suggest:

“… since the hunting with dogs ban came into force, gamekeepers have felt a particular obligation to hammer foxes as hard as they can.”

Later this year (2017) the Mammal Society, in conjunction with the Animal and Plant Health Agency, is due to publish revised population estimates and distribution maps of Britain’s mammal species. Provisional results from the analysis of the Red fox by National Wildlife Management Centre biologist Graham Smith and his colleagues provide an estimate of the British fox population based on data from the NBN Gateway project and average fox density per habitat type. Their analysis estimates that there are some 430,500 foxes in the UK, although the authors do note “there is also uncertainty surrounding the estimate”.

The city fox phenomenon

As counterintuitive as it may appear censusing urban foxes can actually be more difficult than counting rural ones. The only method that can really be applied to urban areas is the counting of fox earths, although getting access to private gardens and secure industrial sites is fraught with complications, and several authors have used this method to estimate fox numbers in various cities. At roughly the same time that Insley was studying New Forest fox densities, MAFF scientist R.J.C. Page was using a similar technique to estimate the population of foxes in the Greater London borough of Hillingdon.

Following his 1973 to 1979 survey, Page estimated there to be at least two foxes per square kilometre, equating to roughly 220 animals. The main problem with this method, and the reason it is typically used on a small scale, is the manpower involved in going around counting all the breeding earths in an area. In parts of America, biologists have been able to survey earths from light aircraft, allowing them to cover a large area in a relatively short period of time, but this is only really practical in open habitats; try counting fox earths in your local wood or forest using Google Maps if you want an appreciation of the difficulty. So, in Britain, during the mid-1980s, Bristol University biologists came up with a very practical solution, using a hitherto un-tapped resource: school children.

In a series of papers to the Journal of Animal Ecology during 1986, Stephen Harris and Jeremy Rayner described how they used questionnaires asking for reports of fox and earth sightings circulated to local councils and school kids to estimate the number of foxes living in Bristol. In the mid-1980s there were an estimated 211 family groups in Bristol; so 211 dogs, 211 vixens and 74 non-breeders, equalling almost 500 adult foxes in the city. When the method was applied to cities elsewhere in the country, it suggested the fox population was largely concentrated along the south coast, around London, central England and a belt across the English-Scottish border. Subsequently, estimates were produced for new UK towns and, by combining all the data, the 1995 estimate of 33,000 urban foxes was made, although at the time the impact of mange had yet to fully reveal itself.

Six years later, in 2001, following the devastating mange epidemic, David Wilkinson and Graham Smith at the Central Science Laboratory in York published a short paper in Mammal Review, in which they presented a preliminary survey of changes in urban fox densities in England and Wales. Between May and November 1997, the researchers sent a questionnaire to 139 councils and 44 local mammal groups asking whether they thought urban fox densities had increased between 1986 and 1997; 156 (85%) responded and 41% thought fox numbers had increased, 42% thought they had remained the same, while 7% believed they had decreased. Care should be taken when interpreting the data because councils were responding based on complaints received from the public, but there was a distinct clumping of respondents from the London area who reported an increase in numbers, while most south-coast regions reported no change.

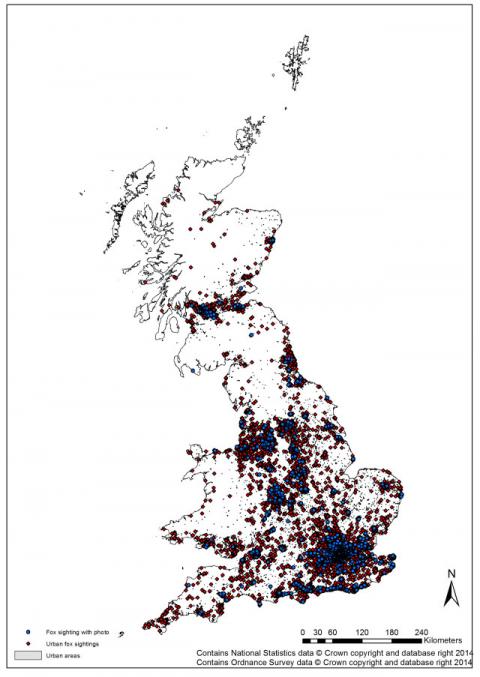

Following the case of a fox biting nine-month-old twins Lola and Isabella Koupparis in Hackney (London) in June 2010, several media outlets ran articles stating that there were about 10,000 foxes in London alone, but it is unclear where these figures came from. The attack on the Koupparis twins indirectly spawned a mini-series called Foxes Live that was broadcast on Channel 4 in May 2012. The series initiated a survey asking people to report fox sightings on an interactive map. The very preliminary analysis of the data from the 11,000 responses received while the series was on air led Dawn Scott (Brighton University) and Phil Baker (Reading University) to an estimate of between 35,000 and 45,000 foxes living in urban Britain.

Scott and Baker published a more thorough analysis of their data in the journal PLoS One during June 2014 and the results make interesting reading, albeit that they stopped short of giving any actual numbers. The biologists analysed a total of 17,422 sightings submitted during April and May 2012, covering a period from mid-January to mid-May of the same year. The data were compared with various previous studies, including an estimate of fox distribution and abundance published by biologists at Bristol University during 1987.

Overall the picture was one of expansion of the Red fox's range in our cities, with no established populations having disappeared and 59 (91%) of the 65 cities reported to have few or no foxes present in 1987 now playing host to these canids. In most areas, sighting distribution suggested fairly low densities: 40% of the cities had fewer than two foxes per 1,000 people, while 90% of cities had fewer than 30 foxes per 1,000 people. Perhaps most interestingly, Scott and her colleagues observed that there was no significant correlation between the average fox density and the number of sightings. In other words, seeing more foxes around isn't necessarily an indication that there are more (or even a lot of) foxes in your neighbourhood.

In mid-December 2016, Dawn Scott and her colleagues presented their final analysis of the survey data to the British Ecological Society’s meeting in Liverpool. Combining the survey data with radio-tracking data the biologists were able to construct computer models to estimate fox density in different English cities, arriving at an estimated urban fox population of 150,000. According to an article in New Scientist, which picked up the story the following month, Bournemouth topped the list of cities with the highest fox densities at 23 foxes per sq-km (60 per sq-mi), with London, Brighton and Newcastle home to 18 (47), 16 (41) and 10 (26) per sq-km (sq-mile), respectively. That’s about one fox for every 300 urban residents and Scott told the New Scientist:

“They are more or less resident in all cities in the UK now.”

This revised analysis was picked up by several media outlets and reported as the fox population having ‘exploded’ to five-times its previous level, but this is an exaggeration. As mentioned above, much of this population expansion is not an increase in density per se, but a reflection that foxes have colonised new cities. Indeed, Scott told Society delegates:

“The densities in the north have actually increased. The densities in the south have not, … It doesn’t look like London is overrun by foxes.”

Furthermore, the 1995 estimate was an educated guess, as is that presented by Scott and her colleagues, albeit it a more robust one. As we’ve discussed, taking local estimates and extrapolating up is a very difficult thing to do and fraught with dangers.

In conclusion, censusing wild foxes is an extremely difficult thing to do and without regular attempts it is impossible to say precisely what is happening to the population. Nonetheless, the data we do have suggests that the national population has probably doubled in the last 20 years or so, with the spread in rural areas having continued apace since the 1980s. In all, there may be just shy of half a million foxes in the UK, with perhaps one-third resident in our towns and cities.