Red Fox Interaction with Humans - Fox in Literature & Film

Reference to the fox as a cunning trickster can be found in some of our oldest literature: that of the Ancient Greeks, the Romans and the Hebrews, although translators of The Bible’s Old Testament appear to have occasionally confused foxes with jackals. Foxes feature in 51 of 6th Century BC Greek writer Aesop’s 600 or so fables and, although he appears to admire their intelligence, they are often portrayed conning another animal. In some fables, however, the fox is used as a surrogate for exploring human emotions, behaviour and lessons in morality. Aesop’s The Lion and the Fox fable, for example, highlights our fear of unfamiliar things and how this fear can be overcome with patience.

Perhaps one of Aesop’s most famous fables, The Fox and the Grapes, tells of a fox lusting after grapes hanging from a vine just out of its reach; the fox tries desperately to reach the grapes but cannot and, in the end, he gives up saying that they weren’t ripe anyway and he didn’t want any sour grapes. This story illustrates a phenomenon that psychologists call “cognitive dissonance”, which essentially means that we reduce our disappointment in not being able to attain something by criticizing it, or telling ourselves/others that we didn’t want it anyway. Rumour has it that the common expression ‘sour grapes’ originates from this fable.

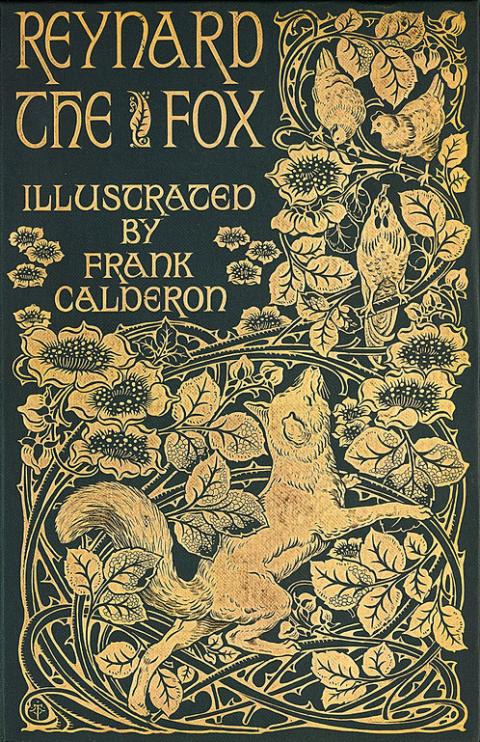

A common incarnation of the fox in early literature was Reynard. Reynard was originally called Reinardus, taking his name from a Latin poem about a wolf called Ysengrimus written around 1148 (possibly by the Flemmish priest Nivardus of Ghent). In the poem Reinardus torments his not-so-bright uncle Ysengrimus. It wasn’t until more than two decades later, in 1175, when Pierre St. Cloud published his poem Roman de Renard that the modern Reynard emerged as a central villain in the saga – the character spread across Europe and arrived in Britain sometime during 1250. Reynard’s profile was raised in Britain by his appearance in Geoffrey Chaucer’s 1390 Nun’s Priest’s Tale, where he appeared as ‘Rossel’. It was apparently from English writer William Claxton’s The Historie of Reynart the Foxe, published in 1481, that Reinardus became known as Reynard.

The stories in which Reynard has appeared have been told and re-told, undergoing the usual modifications, but the central theme remains: that Reynard is a treacherous, vindictive, rebellious and ingenious loner, to be trusted at your peril. The character Reynard the Fox has appeared in various films, books, ballets, cartoons and TV advertisements. The reader is directed to WikiPedia’s page on Reynard for a more detailed history.

More generally, the fox appears frequently in popular culture, featuring in more than 70 movies (animated and live action), referenced in at least a dozen songs, three opera-ballets and countless books. There are also at least five web-comics featuring foxes, including the very popular Faux Pas comic strip by Margaret and Robert Carspecken, which began in 1979. More mainstream was a comic strip series called Marney the Fox. Written and illustrated by Scott Goodall and John Stokes, Marney appeared in the Buster weekly comic and charted the, sometimes harrowing, life of this orphaned fox cub in the Devonshire countryside.

Movies of particular note include the Belstone Fox released in 1973, Gone to Earth in 1950, Mark Rydell’s The Fox released in 1968, the fox taking the lead role in Disney’s Robin Hood and Colin Dann’s 1979 children’s story The Animals of Farthing Wood. Again, the reader is directed to WikiPedia’s page on Foxes in Popular Culture for a fairly comprehensive list.

Before leaving this subject, a fox playing the role of the hero (as it does in Disney’s interpretation of Robin Hood and in Dann’s tale) is interesting because, particularly in children’s literature, such instances are comparatively rare. Indeed, from an early age children encounter animals that are given names and ascribed personalities according to the ecological niche they occupy: typically, predators are ‘bad’ and their prey is ‘good’. Consequently, the fox is usually tagged as the villain of the piece.

As early as the 1870s, we encounter Br'er Fox (pronounced “briar fox”) -- the principal villain in American journalist Joel Chandler Harris’ book, The Uncle Remus Tales -- trying to trick (and being ‘out tricked’ by) Br’er Rabbit. Similarly, we encounter a ‘foxy-whiskered gentleman’ trying to trap the lead character in Beatrix Potter’s 1906 children’s classic The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck.

Predators aren’t, of course, ‘evil’ any more than the animals they prey on are ‘good’. Animals do what they must to survive, without thought for the ‘feelings’ of their adversary. Nonetheless, even as adults, the portrayals of animals that saw us through our childhood can be difficult to shake, and this can cloud our judgement when it comes to interpreting the actions of the wild animals with which we share our planet.