Water Deer - Sexing

There's little sexual dimorphism in water deer, and the similarity in overall appearance is one of the reasons cited for the open (shooting) season being the same for both sexes. In most cases, however, the males possess enlarged upper canine teeth, referred to as tusks, that protrude below the lip and beyond the lower jawline (see: Tusks). In good habitat and with close observation, tusks may be noticeable in bucks as young as six months old, although in their Cambridgeshire fenland study population, Arnold Cooke and Lynne Farrell found that they typically couldn't detect tusks until April, when the deer were around ten months old. The tusks will be fully grown by the time the buck is two years old, at which point identification is further improved by the presence of a dark patch of fur (the labial patch) behind the tooth that helps it stand out (see: Keeping up appearances).

While the presence of large tusks is considered a male trait, females typically possess small canines that protrude only 5-8 mm (0.2-0.3 in.) below the gumline and, in their section on the water deer in the fourth edition of the handbook Mammals of the British Isles, Cooke and Farrell give a total length range (i.e., the length around the outside of the curve) as 16-17 mm (~0.6 in.). In their booklet on the water deer, the same authors mention that the longest female canine they measured in Cambridgeshire protruded only 12 mm (0.5 in.) from the gum, indicating a tooth of some 20 mm (0.8 in.) in total length. Beckerings Estate deer manager Paul Childerley told me that most of the females they see have only small tusks, but occasionally they get one with canines approaching those of the males:

"We have several of those in the season that have small tusks about 1 cm long. But then occasionally we will have those with full set of mature tusks, but a different shape, more curved like a canine. Maybe get one of those a season."

Alongside Childerley's observations, I know of one account from a stalker in Essex who reported having shot a pregnant water deer with "larger-than-normal" tusks in March 2019 and, in 1950, Kenneth Whitehead wrote that there had been two instances of females with tusks from Woburn, the most recent of which was in 1948. Unfortunately, neither Whitehead nor the Essex stalker provide any additional information as to the size of the tusks. I have also seen one adult doe with canines protruding at least 10 mm below the margin of the top lip (image below). Indeed, had it not been for the presence of a distended udder and watching the animal urinate/defaecate, I would've taken the animal for a yearling (subadult) buck. More recently, in a 2022 paper to the Russian journal Zoologicheskii Zhurnal, Pavel Fomenko and colleagues described the morphology of an adult doe, estimated at about two years old, shot in a forest in the south of the Khasansky District of Primorsky krai during late January 2022 - this doe had canines protruding 24 mm (0.9 in.) below the gum. Likewise, in a paper to Reproduction and Breeding published in 2025, Seong-Min Lee reported that three (1.6%) of the 185 does shot in Jangsu County, South Korea, between March and June of 2022 and 2023 exhibitied elongated canines. One female, shot in March 2022, was estimated to be three years old and had canines measuring just over 40 mm (1.6 in.).

More inconspicuously, as we have seen (see: Size and Weight), there is a difference in size between the sexes, with females being consistently heavier and slightly larger in overall dimensions than males, a feature anatomists refer to as inverse dimorphism. Assessing this in the field can be tricky but is possible with experience. Several authors have also reported subtle differences in the shape of the face.

In their 1983 booklet on the water deer, published by the British Deer Society, Cooke and Farrell described how "bucks have blunter facial profiles and thicker necks; does, in contrast, are more delicate in appearance", while, in a 2008 article for Shooting Times, Ian Valentine noted that females "have a slightly squarer muzzle" and, in his 1996 thesis, Endi Zhang observed how the male "possesses a slightly broader mouth despite its overall head size not being evidently bigger ". This has been my experience, too, with the somewhat narrower muzzle giving the female a "slighter" or "daintier" appearance compared with the broader, stockier look of the male, although there is overlap between females and immature males. In a summary of their study at Woodwalton Fen, published in Deer during 2000, Cooke and Farrell mention that:

"Over the years we became more proficient at distinguishing age classes and sexes, e.g. telling young deer from adults or the more graceful females from males."

Some of these sexual differences are evident when studying the skulls, and overall does have larger and narrower skulls than bucks. Yung Kun Kim at the Seoul National University in South Korea and colleagues assessed the skull dimensions of 52 water deer specimens, 31 males and 21 females, finding that nine of the ten cranial measurements they took were larger in nine females. Indeed, only the incisive bone breadth was larger (by about 12%) in males, but a broader muzzle is expected given the large canines the males possess. The researchers, in their 2013 paper to the Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, suggest that the greater demands of single motherhood (i.e., searching for food, suckling and defending the fawns against predators on your own) may account for the larger size.

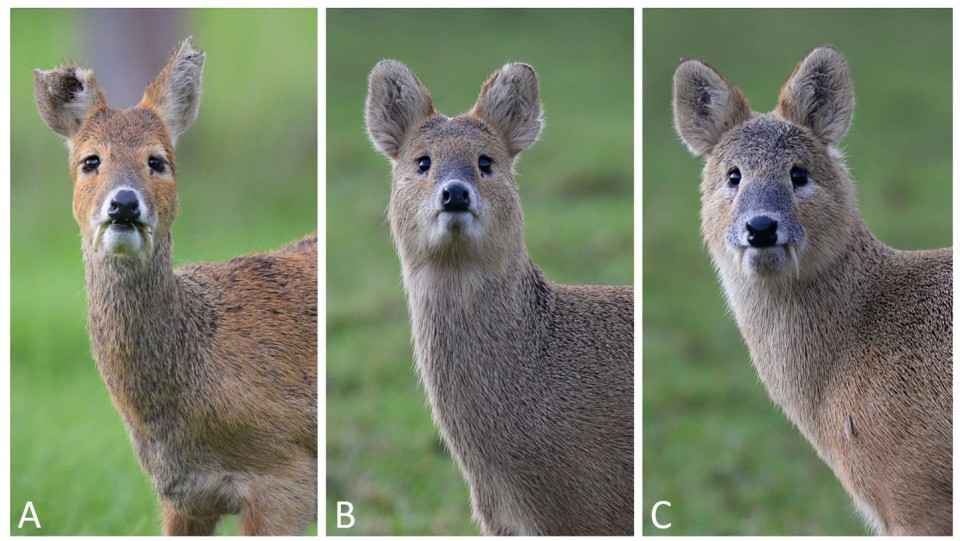

Some reports suggest differences in coat and tails between the sexes. In their 2017 literature review of water deer research to date, for example, Ann-Marie Schilling and Gertrud Rössner note how males are typically dark-coloured around the nose, while in females the area is lighter. Similarly, Cooke and Farrell, in their 1983 account, comment that females have white or pale bands above the nose, while males often have a dark grey or black band. In my experience, the grey speckling does seem more likely to extend into the pale nose band in males than in females. I have also noticed that, during the summer, males at both Whipsnade and at Woburn are often likely to be darker/brick red in their overall coat colour, while females exhibit a lighter/sandier pelage - it doesn't hold true in every case, but it is a frequent observation.

In his chapter on the Artiodactyla in Henry Southern's first edition of The Handbook of British Mammals, published in 1964, Jim Taylor Page included a sketch of the rump of the water deer that suggested males have a shorter and broader tail than females, with a wider u-shaped rump patch underneath. While females do appear to have longer tails than males, being narrower or associated with a pale patch of fur in either summer or winter coat has not been my experience nor that of Arnold Cooke, although he tells me that females at Woodwalton Fen often have "tidier" rear ends than males.

Finally, it is generally possible to identify mature males at distance, even in the absence of tusk information, based on eye and ear damage, which appear to be a common ramification of the way males fight during the rut. Males also engage in frequent scent-marking behaviour during the rut that involves rubbing the gland below their eye on vegetation and scraping the ground. While patrolling their territory, a male will typically hold their tail horizontally, although I have occasionally seen females do this during the winter, too.

Males are called bucks, females are does, and young are fawns.