Water Deer Interaction with Humans - Conservation Efforts

Water deer are held in a handful of captive collections in Europe (see: Water deer in captivity), but as far as I know none include active conservation projects for the species. This is despite recent genetic data suggesting that we may have lineages now extinct in China. Presumably, the lack of conservation interest in Europe is largely a reflection of them being an introduced species and that the feral population in England appears to be flourishing and expanding its range, even in the face of increasing urbanisation, pollution, and poaching. Indeed, it is something of a conservation paradox that a species which might otherwise be subject to eradication methods in the face of a growing population is in such steep decline in much of its native range.

Globally, the conservation status awarded to the water deer by the IUCN has fluctuated over time as the body of supporting data has increased. In 1990, for example, water deer were classed as "Rare", while they were "Vulnerable" in 1994, "Low Risk/Near Threatened" in 1996, and in 2008 they were considered Vulnerable again. In the most recent assessment, carried out in November 2014, Richard Harris and Will Duckworth retained the conservation status of Vulnerable, meaning there's the potential for the species to become extinct in the medium-term unless action is taken:

"Due to the lack of updated information it is not possible to assess the worldwide status of this species with complete certainty. However, a serious decline is nevertheless evident [due to poaching and habitat destruction]. … A decline rate of at least 30% over three generations (approximately 18 years) seems highly plausible."

In Britain

Owing to its introduced status in Britain, the water deer has not received a conservation assessment here, although in their Britain's Mammals 2018, the Mammal Society gave it a Prospect Index rating of "Good", meaning population and range trends were positive. Despite having no species-specific legislative protection in the UK, water deer are covered by both the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Wild Mammals (Protection) Act 1996. Overall, these Acts mean that while it's not illegal to kill water deer one must do so in a specified manner. They cannot be caught in self-locking snares, poisoned, or electrocuted, for example. Similarly, no wild mammal, including all deer, may be kicked, beaten, nailed or otherwise impaled, stabbed, burnt, stoned, crushed, drowned, dragged or asphyxiated with intent to inflict unnecessary suffering. In other words, if you're going to kill a wild mammal you must do it "in a reasonably swift and humane manner". Additionally, the Deer Act (1991) states:

"if any person enters any land without the consent of the owner or occupier or other lawful authority in search or pursuit of any deer with the intention of taking, killing or injuring it, he shall be guilty of an offence [of poaching]".

Someone also commits an offence if they kill a deer without a viable reason (e.g., humane dispatch, significant crop damage, etc.) during the closed seasons set out in Schedule 1 of the Act. Since 2007, before which they could be shot at any time of year, the closed season for water deer in England has covered 1st April to 31st October, inclusive. In other words, water deer can only be hunted in England between November and the end of March.

In March 2010, Statutory Instrument 609 went through the English parliament and Welsh Assembly with the aim of including an additional 63 invasive non-native species to Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Two of these were mammals added to Part 1 of the schedule: wild boar (Sus scrofra) and water deer. Section 14 of the Act makes it illegal to deliberately release a Schedule 9 species into the countryside. The Instrument passed, despite protest from several researchers and the British Deer Society, meaning that it has been illegal to release water deer into the wild in England and Wales without a license from Natural England (or Natural Resources Wales) since 6th April 2010. (See the pop-out note below for clarification on the release of trapped water deer.)

Clarification on Schedule 14 - Emergency in situ assistance

Schedule 14 clarification

Contrary to some statements I have seen on other websites and social media, the UK Government's Guidance on section 14 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, published in 2007, does include a provision for "Emergency in situ assistance", which states that it is not considered an offence under the Act to free an individual covered by Schedule 9 that has become accidentally and unintentionally entrapped, entangled in a fence for example. If the animal is brought into captivity for rehabilitation or veterinary attention, however, it cannot be released back into the wild once deemed fit. Equally, researchers would require a license to trap and release any species on the Schedule for the purpose of scientific study.

In China

Writing in the China Journal of Science and Arts during the mid-1920s, the late naturalist, explorer, artist, and editor Arthur de Carle Sowerby noted how water deer were less common along the Yangtze, in the Nanking and Chinkiang districts to beyond Wuhu, than historically. Later, in 1981, Linmu Xu of the Nanjing Xuanwu Lake Park Management Office in southern China wrote a short article to Acta Zoological Sinica describing how the water deer was "on the verge of extinction" owing to a recent increase in hunting and man-made habitat destruction. Despite at least one successful farming project in the late 1980s, however, water deer conservation didn't really take off until the start of the 21st century. Supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, East China Normal University zoologists Min Chen and Endi Zhang led a project to reintroduce the water deer to Shanghai, where the species had last been recorded in the wild in 1890.

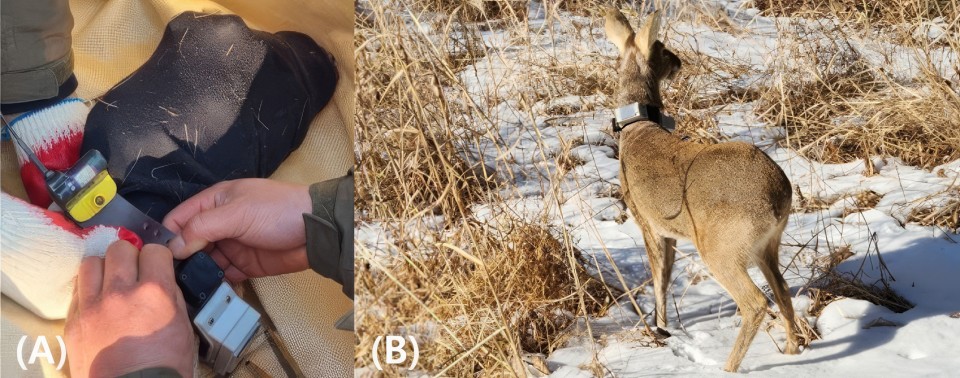

The project got underway in 2006, with 21 animals (seven bucks, 14 does) released into a 540-hectare (1,333 acre) area of Huaxia Park within the green belt of Pudong during March of the following year. The population grew rapidly, the survival rate about 80% per year, and was estimated at 96 individuals by December 2010. In October 2009, 20 deer from the stock were transferred to the Punan woodland in Yexie County, Songjiang District in the southeast of Shanghai for acclimation and to join a further 20 individuals introduced there from the Zhoushan Archipelago in 2008. At the same time, 14 were moved to from Huaxia to Shanghai Binjiang Forest Park during November and five to Shanghai Century Park in the same year. The animals were tagged, and several fitted with radio collars to monitor their movements as well as their influence on the local species. The Punan population also flourished and was estimated at 151 by December 2013, and, apart from some winter supplementation in the first two years, the deer found sufficient food in the native vegetation. The final stage of the project was to release 15 of the acclimated deer into Nanhui East Shoal, a reserve created in July 2007 in the Yangtze River estuary, during early 2010, and 20 in Xinbang woodland in 2012 -- these deer were fitted with GPS collars. By the end of 2013 there were some 300 deer living in the Shanghai region, two captive populations, two semi-captive and two wild/free range populations.

Public support for the reintroduction project was high, and in a 2012 paper to the Sichuan Journal of Zoology, Tie Su and colleagues presented the results of a survey looking at the perceived social value of water deer in Shanghai, completed by students and their families. The results showed just over 92% of the 1,496 questionnaires returned were supportive of a reintroduction project and indicated a social value of 49 million ¥/RMB [£5.4m / €6.2m / US$7.5m] -- i.e., based on the number of respondents who were happy to pay something towards the programme and for ecological protection. Unfortunately, however, Chen and Zhang found evidence of poaching at their project sites, and within the first six months, four deer (three bucks and a doe) had died either through poaching or "unexplained causes" at Nanhui Wildlife Sanctuary. Overall, however, the project was a success and an article in the Shanghai Daily newspaper on 15th January 2013 mentioned:

"Right now 227 Chinese water deer are living in the Binjiang Forest Park and Huaxia Park in Pudong, the Xinbang Forest in Songjiang, and two other parks."

Unfortunately, releases of 12 water deer at a site in Laogang during December 2020 and a further 20 animals in Nanhui in January 2021 suffered significant disturbance and losses through predation from feral domestic dogs on the site. In the space of two months post-release, all 12 animals liberated at Laogang had perished, while 40% died at Nanhui. Several recent authors have also mentioned a continued threat from poaching, although there are several active water deer farms in China that presumably serve to meet some of the demand for traditional medicine and meat products that would otherwise be levied against wild populations.

Presently, the water deer is listed as a Category/Class II species on China's National/State Key Protected Wild Animal List, which highlights a requirement for local conservation action, and as "Vulnerable" by the 2016 China Mammal Red List (assessed in 2015), a status retained in the latest revision, published in May 2023 by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In the same year, the water deer was raised as a "species of concern" in the reedbeds and marshes of Jiangsu in The 2023 IUCN Situation Analysis on Ecosystems of the Yellow Sea with Particular Reference to Intertidal and Associated Coastal Habitats report.

The Korean peninsula

We know very little about the status of water deer in North Korea, although in their 1999 paper to Mammal Review, Changman Won and Kimberley Smith noted that, in 1959, the North Korean government banned hunting for five years following the translocation of 16 deer from Moonchen of Kangwon Province to South Hamgyong Province the previous year. The authors suggest that, as a result of complete protection, the species had increased in number and range. In their literature review of Hydropotes, published in Hystrix in 2017, Ann-Marie Schilling and Gertrud Rössner noted that North and South Korea ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1994, which, among other things, led to regulation of water deer hunting. Yeong-Seok Jo, John Baccus and John Koprowski's summary in their 2018 Mammals of Korea was somewhat bleak, however:

"The North Korean government made a habitat for the species at Mt. Guwol, Hwanghaenam Province a Natural Monument. Despite several releases of Chinese water deer by North Korean government, populations remain small due to illegal snaring for bush meat."

Unfortunately, I know of no up-to-date assessment of the species' conservation in North Korea, while in the South they are widely considered a pest species, although the Gwangju Metropolitan government designated them a "Provincially Protected Species" in 2011. Additionally, many wildlife rescues in South Korea will rescue, rehabilitate and release deer brought to them, which presumably promotes the conservation of the species in the country. In their 2025 case report to Animals, for example, Sohwon Bae described the GPS tracking of a young buck released following femoral head ostectomy surgery to correct a dislocated hip following a road traffic accident in Gangwon-do, South Korea. The deer quickly adapted to being back in the wild, even though it had undergone major surgery.

Some recent genetic work has helped elucidate population connectivity in China and Korea, which may provide a basis for future conservation efforts. In 2011, Jeong-Nam Yu and co-workers assessed the genetic variation in Korean water deer using both mitochondrial and nuclear microsatellite markers. Their data appear to point to a limited gene flow between Korean water deer populations, caused either by habitat fragmentation or an extreme bottleneck in Korea in recent years. Baek-Jun Kim and colleagues, in their 2014 paper to Genes Genetics and Systematics, reported that the genetic diversity of South Korea's water deer was lower than that of the Chinese populations, further supporting limited gene flow. Indeed, in their 2020 paper to the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Rory Putman and his team note that Zhoushan Island populations were significantly differentiated from those in mainland China, while Dafeng and Yancheng populations were significantly differentiated from almost all others (i.e., not Zhoushan Islands) but not from each other. The same result was obtained 14 years earlier, in 2006, by Jie Hu and his colleagues, who analysed the 403 bp fragment of the mtDNA control region (D-loop) and found significant molecular variance between Zhoushan and mainland populations, suggesting that exchanges between the two populations should be avoided and a breeding centre be established for the mainland population. The 2006 study, published in Biochemical Genetics, showed that the Zhoushan population had a lower haplotype diversity than the mainland population, suggesting inbreeding. It also shared only three haplotypes with the mainland population, having seven unique to the archipelago and making it of some conservation significance.