Bats - Interaction with Humans

In many respects, bats fall into the same maligned and misunderstood category as so many other creatures with which we share this planet: spiders, sharks, snakes, jellyfish and such. In the sempiternally funny Ace Ventura II: When Nature Calls, Jack Bernstein’s character Ace Ventura Pet Detective (played by Jim Carey) says of bats:

“They’re hideous! Lifeless beady eyes, clawed feet, huge grotesque wings. Even fangs! They give you rabies, you know?”

Whilst in the caves just outside a village in the Bonai Province, Nambia searching for clues to the disappearance of “Shikaka” (a sacred white bat), Ace confronts bats in a cave with: “Take that you winged spawn of Satan!” and “Die, devil bird!”. While Ace Ventura is obviously only a movie (and now cartoon) character, he does sum up some of the innate phobias many people seem to hold of bats. Indeed, bats form a considerable part of human mythology.

In one Eastern tradition, it is believed that bats were once birds who prayed to be men – their prayers were only half-answered, leaving them with the faces, teeth and hair of men but the wings of birds. It is said that the bats fly at night to avoid being seen and mocked by birds. There are also various dictums about bats flying into your hair and bat droppings leading to baldness. That said, not all traditions fear bats and, in China for example, the word for bat is “fu”, which meaning “happiness”.

Ecosystem engineers

Regardless of personal feelings towards bats, they serve an important function in the ecosystems of the world and are even an important food source for some people (e.g. tribes in Borneo catch, cook and eat fruit bats). Perhaps the most important function these enigmatic mammals serve is in chiropterophily, the act of plant pollination and seed distribution by bats.

In their 2003 paper for the journal Biotropica, Robert Hodgkison at the University of Aberdeen and three co-workers assessed the seed dispersers and pollinators of a lowland Rain Forest in Malaysia. Hodgkison and his team found that some 14% percent of trees in their survey area were at least partially-dependent on fruit bats for pollination and/or seed dispersal. The biologists also noted that the distance seeds get dispersed is dependent on the size of the seed and species of bat. Smaller seeds tend to get greater distances from the parent tree before being deposited because small seeds are consumed and take time to work through the digestive system of the bat. Larger seeds are dropped closer to the parent trees because the bats discard the seeds during feeding and, thus, the seeds only make it as far as the nearest feeding perch or roost.

Similarly, Marco Tschapka at the University of Ulm in Germany found that the understorey palm (Calyptryogyne ghiesbreghtiana) has evolved to offer fruit-like flower tissue as a reward for the bat visiting it. Most fascinating of all, in his 2003 paper in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Tschapka reports that the palm has actually adapted the positioning of its fruit to increase the likelihood of pollination. It seems that the “fruit set” (i.e. amount of fruit tissue) was significantly lower in inflorences (flower-bearing stalks) that were visited only by hovering bats, suggesting that the palm gets better pollination possibilities when the bats perch on it. Video evidence bore out Tschapka’s conclusion, showing that perching bats maintained close body contact with the inflorence, crawling over it and tearing off flowers, while hovering bats merely tore off a flower and flew away with it in their mouth. It is remarkable to think that this palm has evolved to grow fruits that not only attract bats, but are also located in positions sufficiently difficult to access so that the bats must land on the plant and crawl along, making them pick up more pollen than they would were they hovering around the plant. Overall, about 500 plant species in nearly 70 families are pollinated by bats.

More recently, research by Constance Tremlett, a biologist at the University of Southampton, suggests that bats may play a more significant role in the pollination of some plant species than other pollinators do. In an article to Bats in 2018, Tremlett outlines her team’s studies on lesser long-nosed bats (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) in the Sayula Basin of Jalisco, part of central-western Mexico. These bats are pollinators of the cacti in the Basin and their activities contribute to the production of the economically important pitaya fruit. The researchers covered the cacti in meshes of different sizes at different times of day to exclude certain pollinators and found that those cacti pollinated by bats produced more fruit than those pollinated by birds or insects. More importantly, that fruit was also larger and contained more seeds. In the article, Tremlett wrote:

“As fruit size determines market price, bats are increasing both yield and quality of a crop that is important to the local economy.”

As I have mentioned in the feeding section of this article, microbats take a considerable number of insects each year and, as such, represent significant (and free) insecticides. In some countries their droppings are also of significant economic importance, being used to make fertilizers and, in some tribes, pots and plates. In the case of droppings collected from a colony of bats roosting at Fanny’s Lodge in Ireland, two ounces (about 60g) applied to a potato patch gave double the yield of the control patch, without bat poo. Chemical analysis of the droppings revealed that they were 13% nitrogen, 11% phosphorous and 3.5 % potassium – as any gardener will testify, these elements are essential to the growth and metabolism of most plants.

Of the 900 or so species of bat known to science, it is perhaps the vampires that have the worst reputation and are the most entrenched in human mythology. This is not totally unjustified, because vampire bats do occasionally bite people.

Sanguivory and rabies

The first account of a vampire bat biting a human was probably the encounter documented by Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernansex de Oviedo in his A Natural History of the West Indies in 1526; apparently the bat would return to feed on the same man during successive nights, despite the presence of other potential “victims”. More recently, Robert Matthews described the case of an apparent siege of vampire bat attacks that occurred in the small town of Apora in northeast Bahia, Brazil during July 1991. In his book, Nightmares of Nature, Matthews states that casualties of this rare invasion included a six-month-old baby who was bitten repeatedly on the head, nose, arms and legs by a “swarm” of bats, and a 12 year old girl, Marisa dos Santos. The baby was given five rabies shots that saved her life, but unfortunately, died of rabies after four weeks in hospital. It transpired later that the attacks had coincided with intensive logging in nearby forests, which had presumably driven the bats away from their regular feeding grounds. Indeed, vampire attacks on humans are generally associated with removal of livestock or habitat destruction.

It should be noted that, although possible, contraction of rabies from a bat bite is extremely rare. According to Professor of Forensic Medicine at Dundee University Derrick Pounder’s communication to the British Medical Journal in April 2003:

“… in the United Kingdom classic rabies was eliminated from the animal reservoir in the 1920s, and the 20 or so deaths reported since then resulted from infection acquired overseas”.

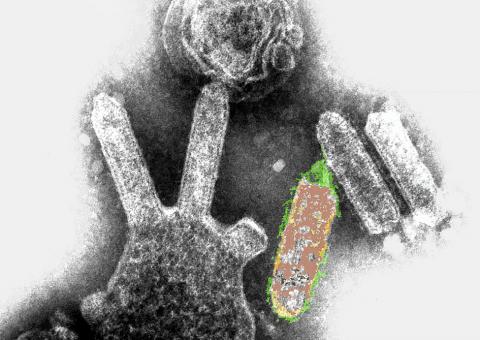

Indeed, according to the World Health Authority’s Rabies Bulletin, there have only been 14 confirmed cases of rabies in bats from the UK since 1977, despite 15,000 animals having been; the most recent case was in a Daubenton’s bat (Myotis daubentonii) from Derbyshire during September 2017. One case, which occurred in 2003, tragically resulted in the death of a 55 year old male bat worker after he was bitten on the ring finger of his left hand. This represented the first, and only, instance of a human catching rabies in Britain since 1977 and the first case of indigenous rabies in a human since 1902. According to a paper documenting this case, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases by Dilip Nathwani at the Ninewells Hospital and Medical School in Dundee and his colleagues, the man was admitted to their hospital suffering from shoulder pain, upper limb paraesthesia and tightness, 19 weeks after being bitten by a Daubenton’s bat. Despite these three cases, Britain is still considered rabies-free, because bat rabies (which exists in two distinct forms, EBLV 1 and 2) is genetically distinct from “classical” rabies.

Rabies is known from bats in several countries, including Australia, America and Brazil. In their short communication to The Veterinary Record, Paulo Roehe and four colleagues report on the first case of cat rabies (caused by a suspected vampire bat bite) in their region of Brazil for 11 years. The paper notes that although reports of vampire bat bites on cattle are ubiquitous, the incidence of cattle rabies in southern Brazil is very low. In mainland Europe, 600 cases of infection with bat rabies were recorded between 1977 and 2000.

Bats in trouble

Broadly speaking, bats are in decline across the globe as a result of our domestic cats, our expansion of housing resulting in habitat loss and our intensification of farming practices. Bats also suffer mortality on our roads and from some manmade structures. For example, Gregory Johnson and his colleagues studied the impact of large-scale wind farms on bats at Buffalo Ridge in Minnesota. Their results, published in American Midland Naturalist during 2003, showed that hoary (Lasiurus cinereus) and eastern red bats (L. borealis) comprised most of the fatalities, and that the number of bat fatalities increased as the wind farm development proceeded. Johnson et al. also found that the timing of the mortalities suggested that victims were migrants, rather than resident breeding bats.

Fortunately, there is a growing appreciation for the importance of chiropterans and many organizations are now in place to champion their conservation and oversee their treatment and rehabilitation. As a result of their hard work, the National Bat Monitoring Programme Annual Report for 2017 reported that populations of the 11 species for which sufficient data are available are either stable or, in the case of the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum), lesser horseshoe bat (R. hipposideros) and common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus), have increased since the late 1990s in Britain. Unfortunately, there are still six species, including the barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus), Alcathoe (Myotis alcathoe) and grey long-eared bat (Plecotus austriacus), for which there are insufficient data to tell what's happening to their populations.

In Britain, the law protects all bat species, making it is an offence to harm one or disturb a roost. Roost disturbance seems of particular importance, because in his 1935 communication to the Irish Naturalist’s Journal, J.E. Flynn reported that, once disturbed, lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) evidently never return to the same place. It is also illegal to handle or keep bats without a license. These measures, combined with the work of volunteer groups and scientists worldwide to erect bat boxes, monitor bat populations and care for and rehabilitate injured bats is leading to the disbanding of many common bat misconceptions. Hopefully, with misapprehensions gone, bats see the worthy of their 50 million years of evolution.