European Badger Size & Appearance

General appearance

In their classic 1983 book, The Badgers of the World, Charles Long and Carl Killingley describe the European badger as "shaggy, squat and powerful", which is highly apt. A combination of long guard hairs in the coat and tough loosely-anchored skin (that needs to accommodate significant fat deposits during the autumn) provide the shaggy appearance, while the short legs and stocky, muscular build (particularly around the neck and shoulders) gives the distinct impression of power. Indeed, in February 2020, the BBC's Winterwatch filmed badgers moving rocks weighing up to 20kg (44 lbs) to get at food underneath; this is about twice the weight of the average badger. This configuration means that badgers move with something of a "bustling swagger".

Typical of their fossorial lifestyle, the eyes and ears are small and the body tapers to a narrow head. All four feet are equipped with six pads (five toes and one plantar) and long non-retractable claws, although the claws on the front feet are larger and thicker than those on the hind paws. The front paws are also larger and broader than the hind ones, being used primarily for excavation. The strong claws, broad pads and muscular chest and legs make badgers highly efficient diggers, but also proficient swimmers and tree climbers. A short, bushy tail of about 12cm/5 in. (up to 20cm/8 in.) is present and probably used in communication. Long, stiff vibrissae (whiskers), black in colour, are present on the head; on the muzzle (around the nose) and above the eyes.

Size

In his 2010 book, Badgers, Tim Roper wrote:

"People are often surprised, when they first see a badger in daylight, by how small it is. On the other hand, badgers can look deceptively large at night, so claims to have seen badgers the size of small bears should be treated with caution."

Indeed, on average, adult badgers grow to between 60 and 80cm long (23-31 inches) long, including the tail. The maximum length is about 105 cm (3.5 ft) and these are normally adult males - males growing larger than females. Weight is much more variable and highly dependent on season. Adults in good habitat typically weigh between 7 and 13 kg (15.5 – 29 lbs) in summer, but this can more than double to between 16 and 24 kg (35 – 53 lbs) in autumn/winter. The average adult weight in autumn, based largely on data from Woodchester park, is about 12kg (26 lbs), while that for spring averages 9kg (20 lbs), illustrating how important fat reserves are for surviving winter. Males are, again on average, one or two kilograms (2.2-4.4 lbs) heavier than females of equivalent age. Body weight is necessarily a function of habitat quality and badgers in low quality areas are likely to weigh less than those in high quality agricultural or urban locations.

Colour & moult

Typically, mature badgers have a silvery-grey to black body and tail, with a paler stomach (the white abdominal fur being very thin) and dark paws. Badgers are easily identified by their characteristic black and white striped face (mask) and white margins to their ears. Variations to this colour scheme, although rare, include white (albino and leucistic), melanistic (very dark) and erythristic (ginger-brown and ginger-red) morphs.

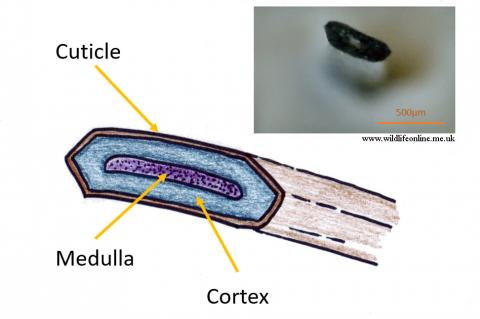

The grey colour of the coat is provided by long guard hairs, which are longer in the winter than summer coat. The guard hairs have a band of eumelanin pigment near the tip such that a hair has a pale tip of about 10mm (0.4 in.) followed by the pigment band of about 20mm (0.8mm), with the remaining half of the hair unpigmented to the base. The guard hairs are oval in cross section, which can be readily felt when rolling them between your fingers. In addition to guard hairs there is a finer underfur that has a felt-like in texture. Underfur hairs are shorter than guard hairs and unpigmented, resulting in white patches appearing on very wet or windswept animals. The guard hairs on the underside and legs are jet black, while those on the neck and face are shorter and either pigmentless (white) or heavily pigmented (black), according to their inclusion in the mask stripe. Guard hairs on the tail are unpigmented.

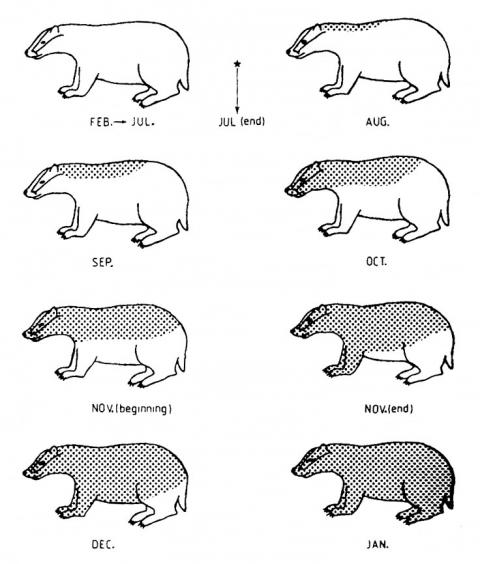

In a 1986 paper to the Canadian Journal of Zoology, Daniel Maurel and colleagues described the moult of the European badger. They observed that hair follicles are inactive between February and July, which means no hair growth takes place. In July, the follicles reactivate and fur (guard and under) shedding and re-growth begins in earnest and the first signs of the new glossier coat was visible on the neck and shoulders by August. The moult progressed from the head, along the back and down the sides, such that all but the belly and hind legs have completed the moult by November. By January the moult is complete. Maurel and his coworkers found no significant variation in the number of either guard or underfur between summer and winter in the coat. In cubs (i.e. less than a year old) there is no specific moult and fur growth is continous, while yearlings moult about a month earlier than adults.

The moult appears to be hormonally-driven and a subsequent study by Maurel and his team found that high levels of circulating testosterone prevented male badgers from moulting. In a 1997 paper to the Journal of Zoology, Paul Stewart and David Macdonald reported that lactating female badgers in their study population delayed their moult until the autumn, significantly later than other adults. The suggestion is that high levels of circulating prolactin may delay moulting, thereby reducing the metabolic drains on the female until her cubs are weaned, although more data are needed to confirm this.

Hair follicle formation in the skin of badgers is interesting because they do not occur singly. Instead a primary follicle forms and spurs the growth of ancillary ones around it. The result is that a guard hair and several underfur hairs grow from a single skin pore.