Summary

Squirrel poxvirus (SQPV), sometimes colloquially called ‘parapox’, is a viral infection that causes swollen lesions on the front paws, flanks and head, particularly around the mouth, nose, eyes and ears. It’s origin in the UK remains unknown, but it is believed to have been introduced with Grey squirrels and a similar infection, albeit caused by a different viral agent, is known in Greys from eastern North America. There is no obvious correlation between the spread of the virus and the spread of the Grey squirrel, however, and in some regions the disease appears to have arrived several years before the Greys. The first confirmed case in Britain was in Norfolk in 1980, although an ‘epidemic virus’ had been observed in Red squirrels since at least 1900, and various attempts to isolate the infectious agent failed.

Once infected, most Red squirrels succumb within about two weeks, although it is estimated that 8-10% survive and there have been recent signs that some resistance may be evolving. Grey squirrels appear largely immune to the British variant of SQPV, with only one recorded fatality in the UK, and are considered carriers of the disease. The virus is spread by contact, but the vectors between Red and Grey in the UK aren’t known. It is suspected that sharing of feeders may be the primary route of infection, with the virus spread in aerosol particles. Studies in Northern Ireland suggest Reds can transmit the virus between each other in saliva and faeces, but Greys cannot transmit it to Reds via these routes. Parasites may transmit the virus from Greys to Reds.

The details

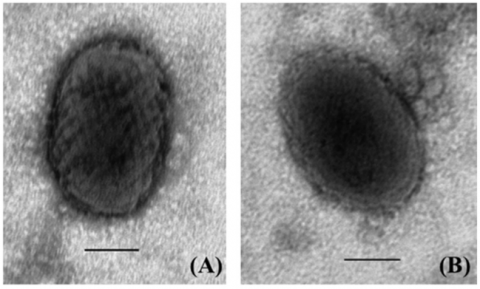

Squirrels, particularly Red squirrels, are susceptible to a viral infection that produces symptoms similar to the myxoma (Leporipoxvirus) and parapox (Parapoxvirus) viruses which cause myxomatosis and orf in rabbits and sheep, respectively. This virus is frequently referred to as the “parapoxvirus”, often shorted to “parapox”, although genomic work by Colin McInnes and colleagues at the Moredun Research Institute in Scotland suggested that it doesn’t actually belong to the Parapoxvirinae subfamily, instead representing a new genus within the Chordopoxvirinae subfamily.

Basically, in their 2006 paper to the Journal of General Virology, McInnes and his colleagues argue that it isn’t technically parapox and, for the purpose of clarity, should simply be referred to as the squirrel poxvirus (SQPV), until we know more about it. More interesting was that, during their study, the team tested the sera from seven Greys trapped in Dane County, Wisconsin (USA) and found antibodies to the British virus, suggesting that SQPV is closely related to the squirrel fibroma virus (also called ‘squirrel pox’) that causes wart-like growths on Greys in North America. The finding also adds weight to the idea that SQPV is derived from Grey squirrels introduced to Britain. Recent work by Gudrun Wibbelt and colleagues, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases in 2017, has identified a strain of the virus that’s genetically distinct from (only 84% similar to) the UK SQPV and cannot be assigned to any of the known poxvirus genera. Wibbelt and his co-workers called this strain “Berlin Squirrelpox Virus” (BerSQPV).

In Red squirrels, infection with SQPV results in ulcerated and bleeding scabs around the eyes, mouth and nose, which later spread to the chest, groin area and the feet. The lesions weep fluid containing the virus particles, which presumably allows the virus to infect the squirrel’s environment. We know very little about how the virus is transmitted, but work by Queen’s University Belfast biologist Lisa Collins and colleagues suggests that the virus can remain viable in the environment for a while and they found viral DNA in the urine, faeces and external parasites of infected squirrels.

In their paper to PLOS One, Collins and her co-workers report on their analysis of squirrels in Northern Ireland. The biologists studied the carcasses of 208 Greys culled as part of a squirrel control plan and 40 Reds found dead by foresters or culled under suspicion of SQPV infection. Interestingly, only one of the Reds had SQPV and the authors commented:

“However, it is somewhat disconcerting that some of the red squirrels testing negative were classed as suspected infected, and consequently culled by local authorities prior to being sent to the laboratory for analysis. This suggests that the mechanisms for identifying potential infected live animals is inaccurate and that culling on this basis alone could, in fact, put extra pressure on already threatened populations.”

The study found viral DNA in the faeces and saliva of the infected Red squirrel, but not in its urine, and in the urine, but not faeces or saliva, of two infected Greys. The sample size is very small, but the suggestion is that the virus can probably be spread in squirrel excretions, and that this is more likely in Reds than Greys owing to their high viral load and diarrhoea when infected. It also hints that Reds may pass the virus between each other at feeders, while it’s unlikely Greys pass it to Reds in this manner. All parasites (fleas and ticks) collected from the infected Red squirrel tested positive for SQPV DNA, as did 27% of the fleas tested from SQPV-Greys. The parasites collected from the SQPV-negative Reds were themselves negative for the virus. As such, this is the first paper to demonstrate the potential for squirrel parasites, which often parasitize both squirrel species, to have a role in SQPV transmission.

The biologists suggest that, although parasites seem like the most likely vectors for the disease, a faecal, urine or saliva route cannot be ruled out. Finally, Collins and her team also found that the virus particles survived better in warm dry conditions than cool, wet ones. Indeed, wet conditions at 15C (59F) appeared to degrade the virus particles completely after 30 days, while a quarter of the virons remained intact after 30 days in dry conditions at 25C (77F). They concluded:

“Limiting the contact between the two species in these areas may provide one means by which to slow or prevent the spread of the disease to remaining red squirrels. In areas where the ranges of the two species overlap, measures to reduce encounter rates are considered essential.”

It is also logical to assume that SQPV could easily spread from mother to kitten during maternal contact, or between fighting or mating individuals.

An ominous arrival

The origin of SQPV in the UK is unknown but it is suspected to have been introduced with Greys. Many conservationists point out that no records of the disease exist in Britain prior to the introduction of the Grey squirrel and, although this may simply coincide with an increased interest in our wildlife and its health in the post-Victorian era, as mentioned above, a study looking at characterising the virus suggested that it was closely related to the fibromatosis affecting Greys in eastern North America, from Ontario in the north to North Carolina in the south. Wherever it came from, its first appearance has been difficult to establish and its presence has only been confirmed relatively recently, which is in no small way a reflection of advances in virology during the last 50 years.

In 1930, Adrian Middleton described how sudden outbreaks of an unidentified epidemic disease had reduced Red squirrel populations significantly, with “numbers falling from a great abundance to absolute scarcity within the course of one or two years”. In a paper to the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Middleton listed 34 districts of England, Wales and Scotland in which Red squirrel populations had declined sharply since 1900; in 14 this disease was recorded as either "Present" or "Severe" but, interestingly, only five corresponded to areas into which Greys had spread. Indeed, Middleton explained:

“It is possible that the grey squirrel may act as a carrier of a disease which is fatal to the red squirrel but non-pathogenic to the grey species, and the occurrence of so many epidemics after the first appearance of the grey squirrel lends force to this view. But if the introduction of disease occurred with the grey squirrel, one would expect to find indications of epidemics among the red species spreading outwards from the points of introduction of the grey. There is no indication, as some of the earliest decreases occurred in the south-west of England [e.g. south-west Devon, 1905], and among the later ones come Norfolk and Lincolnshire [1914] – both comparatively near to the Woburn centre of the grey squirrel.”

In his 1976 pathological report to the Zoological Society of London, Ian Keymer described how two Red squirrels found in different localities in Norfolk during 1973 and ’74 had died of suspected viral infection, but noted that attempts to isolate the virus had failed. Indeed, between 1972 and 1979, 17 unsuccessful attempts were made to isolate the virus from Red squirrels found with swollen eyes. It was not until 1980 that the virus was successfully isolated.

In a short communication to The Veterinary Record in 1981, A.C. Scott and colleagues at MAFF's veterinary lab reported on a Red squirrel found dead in Blickling Park, Norfolk in November 1980. The animal had been observed during the previous winter and appeared healthy, but was found "obviously ill, apparently deaf and blind in one eye" three days prior to its death. Scott and his co-workers noted that this individual was apparently seen fighting with a Grey squirrel three weeks before it was found to be sick. The biologists conducted a post-mortem on the squirrel and were able to use direct electron microscopy to identify large numbers of "parapoxvirus-type particles" from eyelid lesions that were similar to those that cause the disease orf in sheep and conclude:

"The present report is believed to be the first description of poxvirus infection in squirrels in Britain. In the authors' opinion this infection may be a contributory cause of the decline of the red squirrel in East Anglia."

The first confirmed Scottish infection was in a Red found in Lockerbie in May 2007, and infection rates appear low. The first case in Ireland was from two Reds found dead in Tollymore Forest Park, County Down during March 2011. Outside of the UK, SQPV was considered absent from Europe until a new variant was isolated from a juvenile Red squirrel submitted for post-mortem at the Catalan wildlife rehabilitation centre in north-east Spain during July 2010 after being run over. In a note to The Veterinary Record, Elena Obon and colleagues described lesions to the ear tips, paws and tail of the squirrel that they “considered suspicious of a poxvirus infection”. It is noteworthy that there are no records of Grey squirrels in Spain and, unlike the SQPV described from the UK, the disease didn’t produce lesions on the eyelids or lips.

Observations of SQPV appearing in areas where Grey squirrels have yet to colonise raise the question of whether, in addition to the routes Collins and colleagues identified, the disease can be spread by other animals that move between areas with Reds and Greys. That the spread of SQPV in Britain cannot obviously be correlated with the expansion of Grey squirrels may be related to the apparent need for a critical threshold of infected animals. In a paper to EcoHealth in 2008, Anthony Sainsbury and his colleagues analysed the distribution of SQPV cases according to woodland type, which is an indicator of squirrel density, and concluded:

“SQPV disease occurred only in areas of England also inhabited by seropositive gray squirrels, and as the geographical range of gray squirrels expanded, SQPV disease occurred in these new gray squirrel habitats, supporting a role for the gray squirrel as a reservoir host of the virus. There was a delay between the establishment of invading gray squirrels and cases of the disease in red squirrels which implies gray squirrels must reach a threshold number or density before the virus is transmitted to red squirrels.”

Prevalence in the wild

Whether or not the virus was actually introduced to Britain with some Greys, this species certainly seems to act as a reservoir host for it. When an animal has been infected by a virus it develops antibodies for the infection that remain in the blood and are able to act quickly to try to prevent re-infection. By measuring the presence of these antibodies we can tell whether a species has been exposed to an infection and subsequently recovered. We call this seroprevalence.

SQPV seroprevalence in British Greys is high; one study, published in 2000, reports that 136 of the 223 (61%) apparently healthy Grey squirrels tested had antibodies to SQPV, while only four of 140 (3.2%) Reds were seropositive. Perhaps more importantly, all of the seropositive Reds were found dead or dying with symptoms typical of SQPV. In 2013 the National Trust estimated that 40-60% of the UK Grey squirrel population were carriers for squirrelpox, although in their chapter in The Grey Squirrel: Ecology & Management of an Invasive Species in Europe, Tim Dale and Julian Chantry reported that 41 (25%) of the 166 squirrel carcasses they tested from the Sefton Coast on the west coast of the UK were positive for SQPV. Dale and Chantry also noted that males showed a higher prevalence of the virus than females.

In a 2002 paper to the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Daniel Tompkins at the University of Stirling and colleagues wrote:

“... grey squirrel seroprevalence to parapox-virus is high in English and Welsh populations, where the red squirrel is almost extinct, but zero in Scottish and Irish populations, where the decline is far less marked and epidemic outbreaks of infection disease have not been documented.”

Interestingly, in the paper, Tompkins and his colleagues report that one Red squirrel in their study recovered from SQPV, despite suffering weeping and inflammatory lesions for some six weeks. This is interesting, because it represents the first evidence that some Reds have immune systems capable of fighting the virus. Moreover, because this particular individual was found to have an initial antibody response 38% higher than the other three Reds in the experiment and that this antibody response eventually plateaued at a level seen in wild Grey squirrels, the authors suggest that it may be possible to vaccinate Reds against SQPV.

The findings of Thompson and his co-workers have been supported by recent research on the Red squirrels at Formby in Merseyside, where 85% of the population were killed by an epidemic of squirrelpox in November 2007. Following the outbreak, Julian Chantrey and his colleagues at the University of Liverpool carried out blood tests on the survivors and found that just under 10% showed antibodies for the virus, suggesting they had been exposed but recovered.

During part of a Ph.D. study at the university, one Red squirrel was captured displaying facial ulcers indicative of squirrelpox and taken to a local RSPCA hospital where it tested positive for the disease. Following two months of care, however, the squirrel recovered and a further blood test showed it to be free of the virus; it was radio-collared and released back at Formby where it was captured on two subsequent occasions and found to be in good health. Work is also underway to find a vaccine against squirrelpox, and Scotland’s Moredun Research Institute in Midlothian is currently working on this with a recent grant provided by the Ark Wildlife Trust. Interim results from the project are encouraging, with both vaccine candidates providing protection against the wild-type pox virus.

If SQPV originated from the North American squirrel fibroma virus, caused by the viral agent Leporipoxvirus, presumably it has either mutated since its arrival in Britain, or Greys here have subsequently evolved resistance to it. In North America, the virus is relatively common since its initial discovery in free-ranging Greys from Maryland in 1953. Indeed, between autumn 1998 and early summer 1999 several hundred reports of squirrels suffering from fibromatosis were submitted to wildlife biologists in Florida; 20 of those were submitted to a team of wildlife biologists led by Scott Terrell at the University of Florida. In a paper to the Journal of Wildlife Diseases during 2002, the biologists noted that the squirrels died from a combination of emaciation, tissue damage and the overall energy drain imposed by the “massive tumour growth”.

A consistent feature of these infections were growths on the eyelids, as are characteristic of SQPV in British Red squirrels. To date, however, I know of only one record of suspected SQPV from a Grey squirrel in the UK, which comes from the examination of a wild adult squirrel found in Hampshire in 1994. Lesions on its face yielded “parapox-type virus particles”.

Overall, the high seroprevalence of SQPV, combined with the lack of observed symptoms in Greys, suggest that they are a carrier for the virus and capable of passing it on to Reds, to which it is lethal within approximately two weeks.