Summary

Slugs and snails do feature on the diet of hedgehogs and there are examples of captive animals readily eating a hundred or more during feeding experiments. How many slugs are eaten varied with the individual, season and the availability of other prey items. Moreover, it tends to be the very small slugs that are eaten, sometimes in considerable numbers, while mature slugs appear to be taken more rarely. Behavioural observations suggest that hedgehogs often struggle to handle the mucus produced by slugs and snails, particularly large specimens, and this may deter them from eating large gastropods. Molluscs are also a carrier for the lungworm parasite and thier consumption is considered to be a potentially significant route of infection for hedgehogs. There is no evidence that hedgehogs have any discernible impact on slug numbers in gardens, but many gardeners nonetheless consider them allies in "pest control".

The details

I have known many a diligent gardener spend their warm spring and summer evenings treading, or pouring salt, on slugs and snails; this being, in their opinion, the most efficient way to rid their garden of these plant-eating pests. Here in the UK, there is also a reasonably common practice among the more morally conscientious individuals to pluck snails off their prize vegetables and lob them over the fence into a neighbour’s garden or farmer’s field – how much good this does is debatable, given that studies have found snails painted prior to being ejected generally seem to come back. Slugs and snails generally suffer from bad PR, however; biologically they’re fascinating and they play an important ecological role.

A purpose for everything

Slugs and snails (collectively termed gastropods, which is Latin for “belly-footed” and refers to the broad tapered foot on which they glide) are, physiologically-speaking, the same creatures; slugs are effectively snails for whom the shell has been reduced to vestigial status, or lost altogether. I think it is safe to assume that most people are reasonably familiar with the terrestrial snails found in gardens and parks. Land snails, however, comprise a small percentage of the global snail population; the greatest radiation (number of species) and biomass (sheer weight of snail tissue) is to be found in the water, largely in the seas and oceans. Indeed, the Gastropoda is the largest class of the Mollusca phylum -- mollusc is the British spelling, mollusk the American equivalent -- which contains a host of soft-bodied critters including, slugs, snails, clams, limpets, squid and octopuses. Taxonomically, the gastropods comprise about 13 orders, with a staggering number of families and bewildering 60,000 to 75,000 proposed species. Britain is home to about 30 species of slug and 120 species of snail, around 90 of which are terrestrial.

It may not appear so upon cursory inspection, but gastropods have a ‘purpose’ (I use this in an unconscious sense) entirely separate from annoying keen gardeners. Leaving aside, their fascinating and potentially medically-important biology, gastropods are ecologically important too. Most slugs are decomposers; they feed on dead and decaying matter including plants, leaves, fungi, vegetable matter and carrion. (Some, including ‘shelled slugs’ of the genus Testacella and ‘wolf’ snails of the genus Euglandina, are carnivorous and will eat other slugs and snails.)

The decomposition service provided by gastropods serves to recycle organic matter, helping to create and enrich the soil. Indeed, gastropod activity adds partially decomposed organic material called humus to clay particles, forming soil crumbs. As any keen gardener knows, these crumbs are important for water drainage and air circulation within soils. Ultimately, were it not for the activities of slugs and snails (and other decomposers, such as earthworms) the recycling of organic material would cease and nutrients essential to the ecosystems would remain locked up inside the dead plants and animals.

So, slugs form an integral part of the ecosystem, but this doesn’t help pacify those whose vegetable garden or herbaceous border has been decimated by nightly gastropod grazing. Slug and snail damage is particularly problematic because it generally happens under the cover of darkness -- gastropods are very susceptible to dehydration, so they come out at dusk when it’s cool and moist -- and the numbers of gastropods in a single garden can be considerable. Consequently, it is not surprising that gardeners act against these molluscs: slug pellets along with some more environmentally-friendly methods (such as raised beds, crushed eggshells around plants and beer traps) are commonplace in gardens across the UK. Some of the potential issues with slug pellets are discussed elsewhere on this site (see QA).

Molluscs on the menu

Man-made chemicals aside, pretty much everything is eaten by something. Slugs and snails are no exception and there are several species that will eat gastropods: slow-worms; various species of ground beetles, glowworm larvae; spiders and harvestmen; frogs and toads; and several species of bird. The Song thrush is probably the best known for eating snails, but robins, corvids, starlings and blackbirds also make the list of slug-eaters. Some domestic fowl are also partial to gastropods most notably chickens and ducks. I have no experience with chickens, but when my parents owned two free range call ducks, the garden was pretty-much slug free, although this was rather overshadowed by the mess the ducks themselves made while trampling through the flowerbeds. Getting back to the question posed, hedgehogs are also on the list of gastropod predators. Indeed, in his excellent “Partners in slime” article to the May 2003 issue of BBC Wildlife Magazine in May 2003, the Royal Horticultural Society’s Phil Gates describes hedgehogs as “Avid slug-munchers…”.

Dietary studies on hedgehogs from the UK and New Zealand have found that slugs and snails can be quite common dietary components, although the numbers taken seem to vary geographically and only certain species of snail are taken. In his study on the diet of hedgehogs in New Zealand, published in the New Zealand Journal of Science during 1959, Robert Brockie found that 40% of stomachs contained slug remains, while 36% contained snail remains. Similarly, in a paper to the Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society during 1973, P. A. Campbell presented dietary analysis of hedgehogs collected on pasture land in New Zealand, finding the remains of grey field slugs (Agriolimax sp.) in 32% of stomachs and 30% of droppings, representing 4-5% of the diet. Slightly lower values were found by Hans Kruuk in his analysis of hedgehog faeces recovered at a gull colony in England. His data, published in the Journal of Zoology during 1964, showed snail remains (of the genus Cepaea) contributed only 3% of the total weight in 21% of recovered faeces.

In a study of the intestinal contents of hedgehogs collected from Schleswig-Holstein, the northern-most county of Germany (reported by Nigel Reeve in Hedgehogs), W. Grosshans found slug and snail remains in 26% and 32% of samples, respectively. Similar figures were presented by Derek Yalden from his study of 137 hedgehog stomachs collected from an estate in East Anglia. Yalden’s data were published in Acta Theriologica during 1976 and revealed slugs in 31 (23%) stomachs, contributing slightly over 4% of the wet weight; snails were rare, found in only five (0.6%) stomachs. Yalden notes that the numbers of slugs and snails he found in stomach contents were lower than those reported by Brockie and Campbell, writing: “East Anglian hedgehogs eat very few slugs compared with those from the rest of England and the difference is highly significant.” Indeed, the findings of Andrew Wroot during his Ph.D. thesis some eight years later would seem to support Yalden’s conclusion; Wroot noted the presence of slug remains in 51% of samples, while snails were much rarer, occurring in only 5% of samples.

Perhaps of more interest than the number of stomachs or droppings that contain gastropod remains are the figures for the amount of energy that slugs and snails provide the hedgehog with. After all, as Nigel Reeve points out in Hedgehogs, gastropods are easier to digest than insect prey and could thus contribute more, in relative terms, to the hedgehog’s diet than the above percentages suggest. Reeve presents a table summarising the percentage of dietary energy obtained from gastropods according to the studies by Campbell, Yalden, Grosshams and Wroot. The values show considerable variation, from the 1.3% found by Grosshams, through the 3.1% calculated by Yalden and the similarly-matched 5.3% and 5.6% calculated from Campbell’s and Wroot’s data.

As might be expected, the propensity for tackling slugs and snails appears to be related to the age of the hedgehog, although not its sex according to Yalden’s data. During her studies on the food preferences of captive hedgehogs, E. J. Dimelow found that younger, and hence less experienced, animals were more prone to tackle larger, thick-shelled snails – presumably because they had yet to learn the shell was too thick. Even among adult hedgehogs, most are unable to tackle the larger garden snails, such as the Roman snail (Helix pomatia), because their jaws are too weak to penetrate the thick shell. More specifically, Dimelow’s data, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London during 1963, suggest that hedgehogs can only deal with relatively thin-shelled snails up to about 18mm (3/4 inch) in diameter; species such as the white- and brown-lipped snails, of the genus Cepaea, for example. In his 1976 study, Yalden noted that adults three years and over were more likely to tackle gastropods than juveniles one or two years old – slug remains were identified from 35% of adult stomachs, but only 13% of juvenile samples.

There is another possible theory to account for the difference in the numbers of snails taken compared to the number of slugs. It strikes me that this may simply reflect access and/or abundance. My experience of slugs and snails, for example, tends to suggest that they exploit different ‘height niches’; snails crawling up stems to attack aerial appendages, while slugs tend to focus their attention closer to the ground. I am certainly not implying that this is always, or exclusively, the case and snails may attack ground-based plants, while slugs may climb; but this is my observation. Thus, in some gardens at least, snails may be either out or reach of, or more easily missed by, hedgehogs than their shell-less counterparts. Similarly, when removing gastropods from our small city garden, we tend to collect many more slugs than snails, such that hedgehogs may simply be less likely to find a snail than they are a slug.

Bottom of the menu?

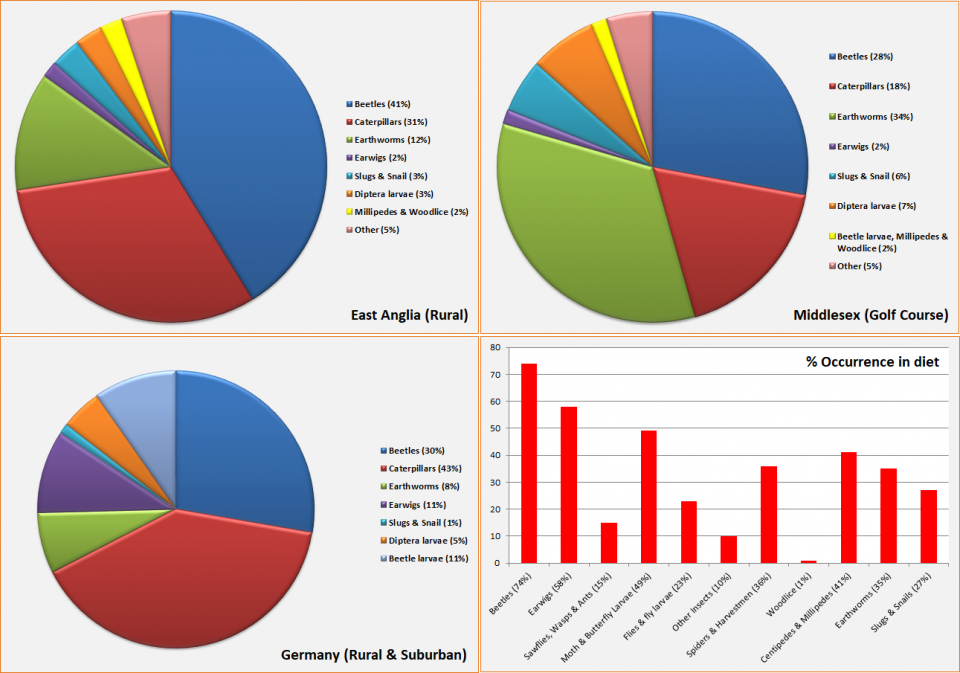

Derek Yalden’s study shows that although gastropods (and slugs more so than snails) may be fairly common in the diet, they pale by comparison to the numbers of insects eaten. Yalden recorded ground beetles and earwigs in 101 (74%) and 79 (58%) of stomachs, respectively. So, why do hedgehogs eat fewer gastropods than other invertebrates? Well, there are two main schools of thought: slugs and snails are consumed with greater frequency, but somehow underrepresented in dietary studies; or hedgehogs find molluscs distasteful, difficult to handle, or otherwise objectionable.

The idea that slugs may contribute more to a hedgehog’s diet than the statistics imply is not difficult to believe. I have already quoted Nigel Reeve, who wrote of the difference in ‘digestibility’ between gastropods and arthropods in his book Hedgehogs, and molluscs are generally only identifiable in stomach contents from their radula (a horny, tooth-bearing strip on the tongue, used for rasping at food) or shell fragments, both of which are fairly resistant to digestive acids. If the hedgehog doesn’t eat any of the shell or the radula, then it is virtually impossible to identify the prey as a slug or snail.

It is perhaps an important point that Yalden’s stomach analysis found mainly small slugs, albeit sometimes in significant quantities (40 in one stomach); but these miniscule molluscs may be even less likely to survive digestion. Additionally, the time of year the survey is conducted may affect the likelihood of finding mollusc remains. Robert Brockie, for example, found slug remains in about 40% of the hog droppings he collected in New Zealand; when split out, however, more than half (56%) were recovered during the summer. Meanwhile, Derek Yalden observed that more slugs were consumed during September and October than in other months by his East Anglian hogs. Thus, seasonality of consumption and superior digestibility may, either individually or combined, lead to an underrepresentation of gastropods in the dietary studies. If slugs and snails aren’t underrepresented, though, could it just be that they are not preferred food items?

There are examples of hedgehogs seeming to relish slugs. In a letter to The Countryman, for example, Gabriel Barlow described watching a hog pulling slugs from the beer trap in his garden until it was empty, before wiping its mouth with its front paws and moving off unsteadily to 'sleep off a hedgehog hangover'. Likewise, in his study on the effect of slug pellets on hedgehogs, Hubert Gemmeke at the German Federal Research Centre in Münster wrote that one of his subjects ate almost 200 of the slugs offered to it. Several people who care for sick/injured hedgehogs or simply put food out for their visiting hogs have, however, noted how well-fed hedgehogs tend to eat fewer garden pests. Certainly, I have seen hedgehogs in our garden feeding on the patio oblivious to the slugs and snails and have heard accounts of hogs feeding on a plate of dog food, ignoring the slugs sharing the dish. So, why might hedgehogs find gastropods less desirable than other prey species?

He slimed me!

Slugs and snails can be difficult to handle because of their size and the mucus they produce. We have seen from Dimelow’s studies that hedgehogs are less able to deal with large, thicker-shelled snails, which immediately limits their options. Without the protection conveyed by a shell, however, slugs are fairer game and size does not seem to be a considerable deterrent; Nigel Reeve notes how hedgehogs will accept slugs up to 15cm (6 inches) long, although the tougher-skinned species (e.g. the great black slugs, Arion spp.) are often rejected. Mollusc mucus does, however, appear distasteful to hedgehogs. During her studies, Dimelow observed hedgehogs to wipe the slime off large slugs (e.g. great grey slugs, Limax spp.) and, in her paper to the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London in 1963, she wrote:

“Snail shells less than I8 mm in diameter were readily cracked provided that they were not too thick. A hedgehog might place a front paw on a snail shell to steady this while attacking the snail. I n the case of slugs the front paws were used frequently to wipe away slime if this w a secreted heavily. Large slugs were eaten piece by piece. Limax maximus was tackled readily even when 15 cm long.”

In their books, Reeve and Morris note how hedgehogs have been observed rolling slugs on the ground in order to remove the mucus.

Slugs produce two types of mucus: a thick gloop, which contains fibres that are used for climbing and, in some species, suspension during reproduction; and a thinner slime that is used for locomotion. The two types of mucus are highly hygroscopic (that is, they readily absorb moisture from the air), which helps prevent the desiccation to which gastropods are extremely susceptible. Additionally, as we have seen above, the mucus may also serve as a defensive mechanism, making the slug distasteful to predators. Indeed, in a 1979 paper to the Canadian Journal of Zoology, the authors reported how, when attacked, the field slug (Deroceras reticulatum) secretes a thick white ‘defence mucus’. I’m not aware that any studies have been conducted looking specifically at the effect of mucus production on the relish with which hedgehogs will accept slugs, but similar studies of insect predators suggest that the mucus can reduce the appeal of gastropods as food.

In a fascinating paper to the journal Biocontrol Science and Technology during 2002, biologists Jacqueline Mair and Gordon Port at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne reported on the influence of mucus production on the degree to which carabid beetles attacked slugs. The scientists offered healthy and ‘stressed’ field slugs (the latter of which have impaired mucus production capacities) to two species of carabid beetles, the black clock ground beetle (Pterostichus madidus) and the woodland ground beetle (Nebria brevicollis). The data showed not only that the beetles preferred small slugs over medium of large ones (as hedgehogs appear to), but also that they took significantly more ‘stressed’ than healthy slugs.

Where the ingenuity of this study really lies is, however, in the second part of the experiment. Mair and Port took some blowfly larvae (Calliphora spp.) that both species of ground beetle are known to readily consume and coated some in slug mucus, before offering them to the beetles. In this test, both species of beetles were noticeably more struck by the mucus-free flies. Within the first five minutes, the black clock beetles had eaten seven slime-free larvae and only a single mucus-covered one; after 24 hours, the number eaten were 17 and three, respectively. The results were similar, although less striking for woodland beetle, who had consumed three control and one test larvae; after 24 hours this had increased slightly to five and two, respectively. From their data, Mair and Port concluded that the defensive mucus produced by healthy slugs hampered attacks by the beetle, writing:

“Results indicate that these generalist beetle species are unable to overcome the defence mucus production of healthy slugs. Slugs sub-lethally poisoned by molluscicides may be a more suitable prey item due to a reduction in defence mucus production.”

Dangerous liaisons

A final circumstance that may lead to hedgehogs finding gastropods undesirable is a lethality one. Gastropods are hosts for lungworm and fluke parasites, which can be transmitted to hedgehogs. Indeed, lungworm infections are remarkably common among hedgehogs in the UK, and can represent a significant source of mortality. Moreover, some have suggested that slugs poisoned by slug pellets may, in turn, poison hedgehogs that eat them, although the jury is still out on this (see QA). Off-hand it seems unlikely that hedgehogs would instinctively know that slugs are potentially “bad” for them.

Nonetheless, if feeding on slugs is either a learned or genetically predisposed behaviour, as opposed to simply being a generic “eat whatever runs slower than you” rule, it is not unrealistic to think that slug predation could become rarer, at least locally. If genes for eating slugs exist, and prove lethal through lungworm infection or poisoning, they are likely to decline in the gene pool. Similarly, if sickness rapidly follows slug consumption, learned avoidance may also occur.

In conclusion, hedgehogs do eat slugs, albeit that the number eaten, and thus the benefit they provide the average gardener, is a matter of opinion and varies considerably based on various factors. With few exceptions, slugs don’t appear to be eaten with particular relish and will often be overlooked if alternate food is available. Furthermore, it is often small slugs that are eaten. Nonetheless, while it is unlikely that the hedgehogs visiting your garden are going to single-handedly rid you of your plant-chomping gastropod pests, they’re part of a ‘natural army’ (including birds, amphibians, slowworms and various beetles) that together help keep the number of slugs and snails down. If you want some ideas on how to garden for wildlife, such that you encourage the species with a ‘penchant for pests’, check out some of the links below.

Gardening for Wildlife Links

Wildlife Trusts - Wildlife Gardening

Beautiful Britain - Wildlife Gardening

RSPB - Gardening for Wildlife

Wild About Gardening

Discover Wildlife - How to Start a Wildlife Garden