The first couple of weeks of spring brought more of the same weather for western parts of the UK, with rain and strong winds ushering in March. That said, although the weather did take on a more showery nature in most parts of the country, despite a bit of a chilly wind we had some decent sunny spells in the first half of the month. Warm air drawn up from the Azores resulted in a couple of days of unprecedented temperatures, with the mercury reaching 16C (61F) in parts of western England. The second half of March was mostly more spring-like, although a stiff cold wind, first from the east and later from the north, pulling down an Arctic airflow, took the edge off the warmth. The northerly flow during the final weekend also brought more cloud and 40-50mph gusts, which caused some localised damage.

The early blue skies and sunshine drew out hundreds of thousands of visitors to popular holiday destinations across the UK during the penultimate weekend of March. Unfortunately, this coincided with the start of the COVID-19 (CV-19) virus getting a grip in Britain and was in direct contrast to what government and medical agencies had asked people to do. Those among us who understand (even only loosely, in my case) what this virus is and how it has been spreading are worried – some are terrified. I don’t want to dwell on this viral pandemic, but there are some important elements to touch upon as they have a direct impact on us as well as the creatures with which we share this planet.

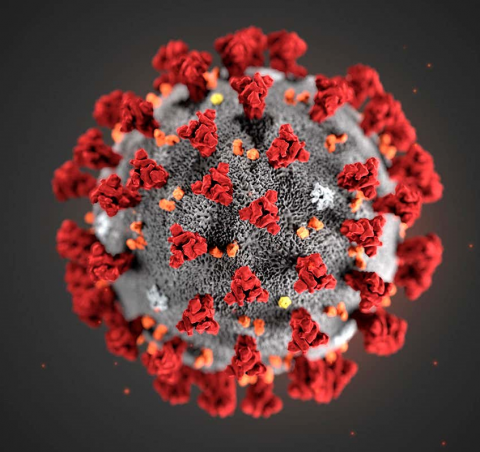

So, what is a virus? With the roots of its name in the Roman word for both “venom” and “sperm”, “creation and destruction in one word” as Carl Zimmer once put it, a virus is technically referred to as a sub-microscopic infectious agent that replicates inside the living cells of its host. Broadly speaking, these are tiny (you could line up about a thousand of them along one edge of a grain of salt) shells of protein containing a handful of genes that are injected into the genetic code of a host cell, hijacking it to make more copies of the virus. We don’t know how many viruses inhabit Earth, although they’ve been found everywhere scientists have looked and one very rough calculation suggests there may be well in excess of two billion species. Even the lungs of a healthy human, which were historically considered sterile, may be home to almost 180 species, with 19 species only recently identified.

Viruses seem to have played a crucial part in the evolution of life on Earth - we probably have them to thank for much of the planet’s oxygen (many microbes appear to have viral roots, for example) - and generally we live peaceably with them without giving it a second thought. In some cases, however, viruses can become pathogenic to humans and we currently know of just over 200 that can infect us – COVID-19 is the latest.

There’s still a lot to learn about COVID-19, but what we do know is that, contrary to some rumours circulating on social media, it did not ‘escape from a lab’ – a recent genetic study suggests it jumped from an animal host, either in its current pathogenic form or in a form that subsequently mutated in its human host to become transmissive.

We don’t know exactly where CV-19 came from and, as we’ve not seen anything quite like it before, we don’t currently have a vaccine. It appears to have originated in China’s Wuhan province in December of last year, and there’s good reason to believe it probably made the leap into humans in their wildlife markets. We’ve seen a similar situation before as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) viral epidemic that killed about 8,000 worldwide in the early 2000s started in China’s Guangdong Province in November 2002; it appears to have made the jump to humans via civets (who caught it from bats) at such a market. In the case of CV-19, pangolins and turtles have been proposed as origin species, although an early suggestion that it originated from a snake now seems unlikely. Either way, we know it is of wildlife origin and focus is being directed at wildlife markets in Asia as a potential source for this and future pathogens, with calls to regulate or even close these venues.

It's times like this when we need to be pragmatic and rational in our actions. As naturalist Adele Brand put it in her recent blog, “viruses spread fast, but misinformation and disinformation have never spread faster”. Indeed, it has never been more important to treat unverified Internet sources with suspicion, particularly when they’re suggesting you take some unsanctioned action to tackle the virus. Currently, in the UK, this means keeping an eye on the NHS website or the Government’s CV-19 site. More broadly, the World Health Organization have a microsite dedicated to coronavirus as does the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, an initiative by the University of Oxford.

Unfortunately, we even need to treat apparent good news stories with skepticism, as the social media post about dolphins appearing in Venice’s canals since the country’s lockdown, which turned out to be a hoax, recently illustrated. As with most stories posted to blogs and social media Snopes and Full Fact are good starting points to find out if something is accurate.

Okay, let’s move on and get back to why you’re really here… wildlife and nature, which is all the more important in these unsettling times.

The current advice from the UK Government is that people can, and should, get outside for exercise once per day during this CV-19 outbreak, while keeping at least 2m (6ft) away from others who aren’t members of your own household. If you’re intending to get out and about to your local allotment, park or woodland for your daily exercise (bearing in mind that driving to such locations for exercise is no longer permitted by most police forces), or even just plan spending more time in your garden, please consider taking part in the People’s Trust for Endangered Species’ Living with Mammals Survey, which is running now.

If you’re If you’re interested in the wildlife to be found this month, check out my Wildlife Watching - April page.

In the News

Conservation news stories that caught my attention last month include a much-needed positive aspect of the CV-19 pandemic, some good news for badgers (and science) and the discovery of a tiny-yet-ferocious dinosaur.

• Air quality improvements: If there’s a positive aspect of the current pandemic, it’s that the widespread working from home, lockdowns and social isolation has resulted in drastically improved air quality across large swathes of the world. New data from the London Air Quality Network, run by King’s College London, reveals that both nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particles known as PM2.5 have declined compared to average levels, particularly along roads. Overall, PM2.5 pollution dropped to 50-66% average levels in London, Birmingham, Bristol and Cardiff and by 25% in Manchester, York and Belfast; smaller declines were recorded in Glasgow and Newcastle. Levels of NO2 fell by up to 50% in London, Birmingham, Bristol and Cardiff, with drops of 10-20% elsewhere. A similar pattern has been observed globally, from China to Italy.

• Badger cull to be phased out: The highly controversial badger cull, which is estimated to have killed some 100,000 badgers over the past seven years at a cost of £60m (€67m / US$75m), is due to be phased out in favour of vaccination trials. Ministers announced early last month that they intend to fund schemes to both vaccinate badgers and improve cattle tests for bovine tb.

• New “super weird” tiny dinosaur species found: A tiny bird-like dinosaur, weighing only 2g (0.07 oz.) but with around 100 sharp teeth, has been discovered preserved in a pebble-sized piece of amber dug out of a mine in Myanmar, China. The dinosaur, named Oculudentavis khaungraae (referencing its eyes, teeth and bird-like characters) by palaeontologists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, appears to have spent its time hunting in forests during the daytime nearly 100 million years ago,in the Mesozoic.

Discoveries of the Month

Puffins aren’t such birdbrains

Back in November I featured the discovery of the first documented case of tool use in “Priscilla”, a Visayan warty pig (Sus cebifrons) living at the Ménagerie at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Examples of animals using tools, be it Priscilla or “David Greybeard”, the chimpanzee that Jane Goodall photographed using blades of grass to get at termites deep within their mound in Gombe National park, often both fascinate and perturb us in equal measure.

Tool use was a long-held bastion of humanity, one of the last remaining things that separated us from “the animals”. There are two types: true and borderline. True tool use involves the manipulation of an object detached from the substrate (a stick or blade of grass, for example), while borderline tool use is where the tool remains part of the substrate (e.g. using a tree as a scratching post). Seeing animals carry and manipulate objects to help make their lives easier or tasks more productive chips away at this quixotic line in the sand and causes us to continually reassess what it means to be human. Researchers studying puffins have recently watched these enigmatic birds waddle all over that line, and to a rather human-like end.

With multicoloured (yellow, blue and red) beaks, red eye rings and a comical waddling gait, puffins (Fratercula arctica) are unmistakable. These medium-sized black and white seabirds are listed as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN’s Red List and, as such, are included on the Red list of UK Birds of Conservation Concern. The introduction of alien predators and environmental disasters, such as the Torrey Canyon oil spill in 1967, all had a hand in the puffin’s decline, but it is climate change and the impact this has on their food (mainly sand eels) that’s caused them probably the greatest problems. Nesting colonies are found around the north Atlantic and, although the largest are in Iceland and Norway, Britain is thought to be home to around 10% of the world’s puffins, with Skomer Island (Ynys Sgomer) in Wales being arguably the most important UK deme.

The puffins of Skomer have been monitored using remote cameras (trailcams) since June 2012 by zoologists at the University of Oxford and the Wildlife Trust of South Wales, while a more recent study of birds on Iceland’s Grimsey Island, some 1,700km (1,050 miles) to the north, was initiated in July 2018 by researchers at the South Iceland Nature Research Centre. In a paper to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published in January, a joint team of UK and Icelandic scientists describe two instances of the same tool use, one on each island.

On the 18th June 2014, an adult puffin on Skomer Island was observed sitting on the water with a wooden stick in its bill, which it proceeded to use to scratch its back for a few seconds before taking off with its “scratch-back”. Almost exactly four years later, on the 13th July 2018, on Grimsey Island, one of the trailcams recorded a short clip of another adult bird picking up a wooden stick from the ground and using it to scratch its chest. The bird subsequently appears to drop the stick and wander off, suggesting that the intention had not been to have taken it back as nesting material.

These observations are particularly interesting because the use of tools for so-called “self-maintenance” is comparatively rare, with most documented tool using being directed at obtaining food. Indeed, wild chimps and elephants and captive parrots are the only other species we know to use tools in this way. In their paper, the scientists, led by Annette Fayet at Oxford, propose that the sticks are being used either to scratch an itch or dislodge external parasites. Indeed, seabird ticks (Ixodes uriae) were particularly abundant on Grimsey Island during the summer of 2018. Either way, Fayet and her colleagues suggest their observations, coupled with the puffins’ need to juggle a variety of physical and social information to make complex decisions while foraging in patchy and unpredictable environments, indicates that:

“… seabirds’ cognitive capacities may have been considerably underestimated.”

Reference: Fayet, A.L. et al. (2020). Evidence of tool use in a seabird. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117(3): 1277-1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918060117.

Yawning may help relieve anxiety

Despite being only a relatively short summary, this research piece has taken me a long time to write. On reflection, a lazy, sunny Sunday afternoon, post-lunch, in “lockdown” is perhaps not the best time to be writing about yawning. The mere thought of it is enough to start me off!

Many of us no doubt associate yawning with being tired and the desire to sleep, and it certainly is a behaviour commonly observed in the run up to, and immediately after, a period of sleep. Contrary to popular misconception, however, yawning is not all about your body telling you your batteries need recharging. It’s a deeply rooted behaviour and we humans do it while still in the womb from at least 24 weeks.

Yawning is a common behaviour that has been documented in a wide range of vertebrates, from snakes to chimps, and it’s seen during a broad range of situations such that ethologists, scientists who study animal behaviour, split theories as to its purpose into two groups: physiological and social hypotheses.

Physiological theories for yawns propose that they serve a “homeostatic restorative function”. In other words, some biological factor is out of whack and needs correcting. Some researchers suggest, controversially it must be noted, that we yawn more when the level of carbon dioxide in our blood rises, and yawning brings an influx of new oxygen that helps refresh us. Along similar lines, it has been proposed that yawning may help to cool and reduce pressure on the brain during periods of increased activity, as well as altering various neurotransmitters.

More recently, research has been directed at assessing the potential social causes behind yawning. Most of us can testify that yawning is contagious; even a photo of a different species yawning is enough to trigger the same response in us, and we now know that dogs yawn and get sleepy when they see a person yawn, indicating this transmission works both ways. Furthermore, a 2007 study that found autistic children do not yawn more (indeed, yawn less) when they watch videos of other children yawning adds support to the theory that contagious yawning is linked in some way to empathy and social cohesion. Such contagious behaviour may be a herd response that helps all members of a family unit settle down to sleep together, for example, but this is only one potential social element of the instinct – yawning may also be a sign of anxiety.

Over the 14 months between May 2013 and July 2014, a team of researchers led by Elisabetta Palagi at the University of Pisa in Italy studied the yawning behaviour in 13 captive South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens) living at Spain’s Oceanogràfic aquarium. The scientists sifted through 29 hours of video footage of the sea lions to extract the 433 times the pinnipeds yawned, noting the behaviour and interactions immediately beforehand.

The data, published in the journal Scientific Reports at the end of last year, reveal, unsurprisingly, that in the majority of instances the sea lions yawned while dozing on platforms or rocks in the aquarium, often with their eyes closed. Of greater interest, however, was that yawning and self-scratching (a sign of anxiety in this species) significantly increased immediately after an inimical encounter, in both the aggressor and victim. This, Palagi and her team suggest, implies that yawning episodes may indicate anxiety in sea lions and/or function as a stress-release mechanism.

Reference: Palagi, E. et al. (2019). Spontaneous yawning and its potential functions in South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens). Sci. Rep. 9: 17226. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53613-4.