The most absolutely honest answer to the question "are there white sharks in British waters?" is that we simply do not know for sure, although there are several reports that suggest they may be occasional visitors. There have been many stories in the media over recent years but, at the time of writing (November 2019) there has never been a single confirmed sighting of a great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) in UK waters. Before I am inundated with e-mails linking to The Sun newspaper's website, let's take a moment to look at the evidence.

If you were a regular reader of the tabloids around the turn of the millennium, you might've been forgiven for thinking that anyone dipping their toe in the Great British briny, otherwise referred to as the north east Atlantic, ran a considerable risk of being torn limb from limb. Indeed, according to an article in The Sun newspaper during 2003, great white sharks were "patrolling Britain's shores"! So, how did this media hyperbole begin?

So it begins…

On 24th August 1999, a group fishing aboard the vessel Blue Fox (skippered by Mike Turner and Phil Britts) off Cambeak Head near Crackington Haven in Cornwall were in the process of releasing a 9-14kg (20-30 lb) tope shark (Galeorhinus galeus) they had caught, when they were investigated by a large shark, estimated to be around 4.6m (15ft) long.

The crew described how the shark passed the stern and rolled slightly on to its side, exposing its white belly, before swimming away. The crew, which included two angling journalists, had seen many porbeagles (Lamna nasus), shortfin makos (Isurus oxyrinchus) and basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) during their trips and were adamant the shark that investigated them was any of these. Additionally, Mr Turner spent many years living off a boat in South Africa and is very familiar with white sharks; he is certain the animal he saw was a great white. There were cameras on board, but, as one of the Blue Fox's regular customers, Adrian Bradyshaw, pointed out to me:

"The capture on film (let alone a good quality identifying photo) of a fleeting event, such as the appearance of a GW at the side of your boat, to disappear as quickly as it materialised, is no mean feat."

So, unfortunately, no photos of the Blue Fox's shark exist and, despite the remarkable credibility of the accounts given by the customers and crew, there remains no unquestionable proof of the shark species involved. The credibility of the Blue Fox encounter was subsequently enhanced by two events that occurred shortly afterwards. The day after the Blue Fox incident, in almost exactly the same spot, two men fishing for tope from the boat Blissful watched as a large shark, which they said was as least as long as their 5.2m (17ft) boat, surfaced and bit two-thirds off the shark they were hauling in.

The full description of the shark's appearance and behaviour towards the boat match perfectly that given by Mr Britts and his colleagues the day before. Finally, approximately two weeks later, in September 1999, a lobster fisherman reported a large shark, estimated to be about 4.6m, entangled in his rope off Tintagel Head, about 18km (12 mi.) away from the Blue Fox sighting. The crew described the shark as having a slate-grey back, bright white belly and a crescent-shaped mouth with triangular teeth. Unfortunately, because the carcass had no commercial value to the fisherman, it was cut loose without being photographed; the description, however, makes it hard to believe it could be anything other than a white shark.

The Blue Fox story made the headlines in the British press about two days after it happened and 'shark fever' began. A day or so later, some "evidence" of white shark activity was presented by The Sun, in the form of a shaky home movie showing a large shark swimming just offshore from Tintagel in north Cornwall. The footage undoubtedly showed a basking shark, which are frequent visitors to the south coast during summer, and not the great white that the newspaper asserted. The original sightings were, nonetheless, sufficiently tantalizing to spur a privately funded 13-day expedition led by Richard Peirce to the waters off north Devon and Cornwall, during August 2003. Unfortunately, the expedition found no trace of white sharks in the 104km (70 mi.) stretch they explored between Trevose Head and Hartland Point. In fact, quite disturbingly, the group found very few sharks at all; considering their use of chum, there should have been considerably more sharks about and the results of the survey point to a serious decline in numbers.

As it happens, Mr Peirce's expedition coincided with the re-firing of the 'British white shark debate' following a couple of sightings in June and July 2003. The latter of these was a report made by a 14 year old girl who, using binoculars from her position about 18m (60ft) up on a cliff-top, watched what she perceived, based on the size of dolphins nearby, to be a 3.5m (12ft) Great white feeding on a shoal of fish off Baggy Point, near Croyde in North Devon. The shark apparently exhibited 'indicative bite-and-spit technique' while feeding next to the pier. The description given of the shark was extremely detailed, almost textbook, for the conditions. Unfortunately, nobody else appears to have seen the shark in question and there is no other evidence to confirm the presence of a white shark; some shark biologists have also questioned aspects of her description.

The topic died down for a while before re-emerging in the papers briefly during March 2005, when several dead porpoises washed up along the Durham coast with what appeared to be large bite marks in them. Closer inspection, however, suggested that the mammals were caught as bycatch, dumped back in the water and the "bite marks" were caused by seagulls and other small scavengers pecking at exposed flesh. The same thing happened in May 2016, when The Daily Mail carried a story about a porpoise that washed ashore at Happisburgh in Norfolk sporting injuries that "were 'almost certainly,' caused by a shark". In fact, looking at the photos of the carcass it appears the same as all the others -- a dead porpoise was scavenged by various marine animals and it creates a series of wounds that give the incorrect impression it was attacked by something larger.

Alternative facts?

Despite some very credible sightings off Scotland during late 2003 and mid-2005 (see below), the topic went cold in the media until the summer of 2007, when two more alleged white shark sightings came out of Cornwall.

The first to hit the headlines involved the appearance of a large animal breaching (i.e., rising out of, and crashing back into, the water). The spectacle was caught on tape by a tourist filming dolphins about 200 yards off Porthmeor Beach in St. Ives during June. When the video was played back, the gentleman saw what appeared to be a large shark breaching among the dolphins. The video was picked up by The Sun and made the front page of their 28th July 2007 edition. The stills appeared in the paper itself, while the video was put on the newspaper's website. The online version of the video was understandably compressed for easy web transfer, but the low bitrate and compression artefacts made it difficult to make out the dolphins, let alone the shark. One assumes, however, that the experts who commented on the footage, the Natural History Museum's Fish Curator Oliver Crimmen and the Shark Trust's Richard Peirce, probably saw the original footage, which one can imagine was of significantly better quality. (Having read Richard Peirce's account in his Sharks of British Seas book, I'm not so sure anymore!) Regardless, the experts gave the only response they could under the circumstances: that the animal in the video looked like a large shark and a great white could not be ruled out. That was apparently all some of the tabloids needed to hear and declared a "killer fish" present in UK waters.

A couple of days after the original footage went public, The Sun ran a second story after they were sent a video of a shark fin slicing through the water near to where the dolphins were filmed. This shark was filmed by a tourist from a pleasure cruise just off St. Ives only a few days after the dolphin footage was taken. Once again, video stills made the papers and the video was uploaded to The Sun's website. The fin of this particular shark, coupled with its motion through the water, leaves no doubt that it was a basking shark. Unfortunately, despite reliable sources from The Shark Trust and Plymouth Marine Aquarium stating categorically that the footage is of a 3.6m (12ft) Cetorhinus maximus, two misidentifications by people involved with shark education -- one by a curator at Birmingham Sealife Centre and a second by a former Discovery Channel Shark Week presenter -- led to a headline of "Girl Great white is Maneater" in The Sun.

Worse than a couple of misidentifications, several other myths appeared in an interview published in The Sun. It is always difficult to interpret quotations in the media but, seemingly based entirely on fin colouration, the former Shark Week presenter reputedly identified the shark as a female great white. He is quoted as saying "That's definitely a Great white -- probably an adult female about 12ft long. Her mate will be close by." Frankly, this is pure unfounded speculation.

There is insufficient sexual dimorphism in sharks to determine sex without clasper analysis, and I have never come across anything in the literature to suggest it is possible to sex any species of shark based on the colour of their dorsal fin. Furthermore, data on white shark courtship and mating are frustratingly scant -- mating has never been observed and only one description of possible courtship behaviour exists. In a second quote from this Australian-born marine biologist he apparently says of the video:

"I've seen hundreds of Great whites in all weathers -- light, dark, morning and evening -- and that dorsal fin cutting through the water is quick, thick and the correct shape."

I have never been fortunate enough to encounter a great white, so arguably I'm insufficiently experienced to challenge such a statement. Nonetheless, based on fin morphometrics, the latter part of the statement is incorrect. There are other inaccuracies within the interview, which are mixed with genuine observations (e.g., that white sharks migrate vast distances) as well as some reasonably sage general water-safety advice. Overall, it is a confusing piece that has the potential to seriously misinform readers, but ultimately nobody in the shark research community who saw the footage was ever in any doubt that it was a basking shark.

Great white wheeze

Hot on the heels of the 'breach' and 'basker' videos, came the 'spy-hopping hoax'. Spy-hopping is the name given to the curious behaviour during which sharks and some marine mammals, particularly whales, hang vertically (or at a roughly 40-degree angle) in the water column, with their head out of the water. This behaviour appears to be the shark attempting to see what's happening on the surface. Given the difference in density between the air and water, however, their vision would be blurred at best, and this seems an unlikely explanation. It has also been suggested that spy-hopping might be a way of scaring seals and sea lions off rocks and into the water, although one might argue whether going into the water would be the animal's first reaction upon seeing a white shark.

A third theory proposes that spy-hopping might be a method of sampling airborne odours -- volatile compounds are likely to disperse farther and faster in the air than in the water, and a similar behaviour was described in oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) by two biologists at Moscow's Research Institute of Human Morphology in a 1994 paper to the Journal of Ichthyology. Finally, a fourth explanation is prompted by the observation that spy-hopping only seems to occur in baited situations; it isn't seen during observations of sharks under 'natural' conditions (i.e., without chum/bait). This, it is suggested, points to it being a response to hyperstimulation. Whatever the reason, it is a fairly well-known behaviour in white sharks and just such a photo appeared on the front cover of the Newquay Guardian on 31st July 2007, accompanied by the headline "Great white spotted in resort waters".

A local man claimed to have taken the photo while out fishing for mackerel off Towan Head, Newquay in Cornwall. In this case there was no doubt that the photo was of Carcharodon carcharias, although there were several not-so-niggling inconsistencies with the shots. There were two main problems: the photo was a perfect image of a white shark in glassy seas, despite having been taken with a telephoto lens from about 30m (100 ft) in Cornwall's choppy waters; also, if the shark was 30m from the boat, why was it spy hopping? (Sharks seem to do this when they approach objects, rather than swimming along with their noses out of the water.)

These apparent discontinuities raised the suspicions of most of the shark biologists and photographers to whom it was shown. Obviously, the tabloids picked up on this photo and in 1st August edition of The Sun, Doug Herdson, a biologist at the National Marine Aquarium in Plymouth at the time, was misquoted as saying that "it was the first confirmed sighting of the legendary creature in UK waters"; what Doug actually said was that the photo showed a great white and that, although it was not impossible for this species to inhabit UK waters, there was simply no way of telling where the photo had been taken.

Perhaps the ultimate death knell for the photo came in the form of a quote from the Newquay Harbour Master, who told The Times newspaper that "... the Benita Ann, the boat that [the local man] claimed to have been fishing from, had been sold to someone in Scotland 15 years ago and had not been back in the area." On 9th August, the photographer admitted that the photo was taken during a recent fishing trip off Cape Town in South Africa, telling The Guardian newspaper he "... just sent [the photo] in as a joke. I didn't expect anyone to be daft enough to take it seriously." The chairman of Newquay Chamber of Commerce was unimpressed, telling The Guardian that the stormy summer had been enough for Cornwall to deal with, without people spreading malicious material of this nature. Nonetheless, the Cornwall Tourist Board disagreed, telling the paper that the "great, great white wheeze" had actually been good for the area, providing beneficial publicity and apparently failing to discourage people from visiting the region. With this case exposed as a fraud, it leaves one credible report of possible white shark spy-hopping behaviour off Britain, from Looe in Cornwall -- see below.

The debate was reignited the following year, when several other cases made the British press. At the beginning of 2008 two incidents of marine mammals washing ashore around the UK, with wounds appearing similar to those that could have been inflicted by a large predatory shark, appeared in the press. This first made the headlines in The Sun on 3rd January when a dead seal sporting what looked like a large bite mark washed ashore on a lifeboat slipway in Sheringham on the Norfolk coast. Analysis of photos by various shark experts (including Ian Fergusson, George Burgess and Malcolm Francis) concluded that it could have been inflicted either by a great white or a large mako, but without tooth fragments it is impossible to say for sure which.

The second incident made the pages of The Daily Mail on 8th January, with implications of the involvement of a "rogue killer shark". The photo showed the carcass of a porpoise that washed ashore just south of Aldeburgh in Suffolk. The wounds on the carcass seem, however, just as likely to have been caused by a boat propeller and subsequently opened up by scavengers. The Shark Trust were quick to point out that it is quite common for all kinds of stuff to wash up along our shores when we get strong easterly winds and that, even if either incident could be conclusively linked to white shark predation, there is no way to know how far offshore the attack or scavenging happened.

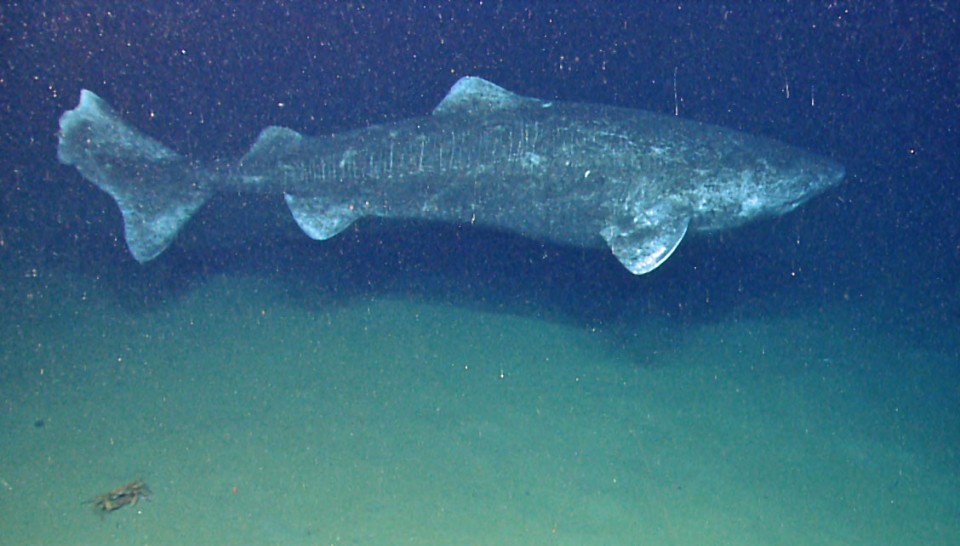

In August 2008, two shark-related articles made the pages of The Sun. The first showed stills taken from a video shot by a remote controlled vehicle working around the Kittiwake Oil Platform, situated 120 miles (178 km) off the coast of Aberdeen. The video clearly shows a predatory shark, but it's not a great white. The shape of the dorsal fin, rounded apex and straight posterior margin, and the white tip at the bottom trailing edge of its free rear tip is indicative of a porbeagle shark. Unfortunately, in one of the accompanying tabloid articles, Doug Herdson was again misquoted; in an open e-mail to a shark discussion list (reproduced here with his permission), he wrote:

"When the photo concerned was sent through to me, I immediately phoned him back and told him that as expected it was definitely a Porbeagle and went through the identifying features with him. I told him that though related to and similar to a white shark there was no possibility that this was one. ... I made no mention about waters around rigs being warmer; is it? And said that they can occur from 5° to 22°C, preferring 14° to 17°C, hence they would have no problem in North Sea waters."

The second article appeared in The Sun three days later and contained a photo of a shark tooth found on a Menai Strait beach, near Anglesey in north Wales. (Interestingly, the photo showed what looks to be a beach at Rhosneigr, which isn't actually along the Menai Strait, but about eight miles to the north-west). The tooth is almost certainly from a great white and it looks to be one from the lower jaw. This would be a very interesting discovery were it not for one niggling detail: the small hole drilled neatly into the tooth root, suggesting it came off a necklace or keychain.

The evidence

With so many of the white shark 'sightings' made to date either highly ambiguous or obviously a case of mistaken identity, are there any compelling reports to suggest great whites do come to our shores? We're still lacking anything concrete, but, contrary to popular misconception, the idea that white sharks might visit UK waters is not new and there are credible reports dating back to at least the 1970s. In his fascinating 2008 book Sharks in British Seas, Shark Trust chairman Richard Peirce (who actively collects and investigates such reports) explained that seven of the 70 to 80 reports of possible white shark encounters he'd received remained credible following further examination. I will summarise some of these credible reports, but readers interested in a more detailed appraisal are directed to Mr Peirce's Sharks in British Seas book or film, or his more recent (2016) book, The U.K. Great White Enigma.

The first credible account of which I am aware involved a white shark reportedly checking out a shark fisherman off the southeast coast of Cornwall. In July 1970, Looe-based angler John Reynolds was pulling in his chum bags and fishing lines at about 3pm when a large shark surfaced a few feet behind his boat, stuck its head out of the water and looked at John before slipping back beneath the surface and swimming away. Twenty-nine years later we have the Blue Fox's encounter and, three years after that, another report came to light. In July 2002, a lobster fisherman working the waters northeast of Cornwall's Quies Islands spotted something large breach out of the water; apparently, closer inspection found lots of blood and seal "bits" in the water.

Shortfin mako, basking and thresher (Alopias vulpinnus) sharks are both known to breach, but great whites are the only sharks known to attack pinnipeds in this way. The only other animal that is seen to breach when attacking seals is the killer whale, Orcinus orca, and these mammals are found in UK waters. The fisherman had seen killer whales before, thought, and was certain the breaching animal he saw was not one. Two days after this sighting a sailor reported a large shark that wasn't, according to the witness, a basking shark following his boat for much of the journey from Padstow to Newquay, through the waters in which the reported breach occurred.

On 4th July 2003, a party of four divers provided a very credible description of the suspected great white that came to inspect their dive boat as they were preparing to enter the water off the western edge of the Summer Isles, near Ullapool. Among the party was a doctor who provided a very detailed description of the 5+m (16.5 ft.) shark and its behaviour towards the vessel. Having been looking for basking sharks to swim with, the party were sure the shark they saw was not one. In his book, Mr Peirce wrote of this account: "I believe that Dr Greenstreet and his party saw a great white shark".

A couple of weeks later, on 15th July, George Carter and Dod Bremner encountered a large shark, estimated to be at least 5.5m (18ft) long, entangled in one of their coding nets off Lybster, just off northeast Scotland's east Caithness Coast. In a short paper to the Glasgow Naturalist in 2008, Mr Carter wrote: "The shark was broad-headed and the steely-grey dorsal surface was smooth, unlike that of a basking shark." Both fishermen agreed that the shark wasn't a "muldoan" (a local name for a basking shark); they saw enough of the tail to rule out a thresher shark and eliminated a porbeagle based on size. Mr Carter went on to say: "Having checked though many books and guides we concluded that it was possibly a Great White Shark Carcharodon carcharias, but we could not be 100% certain."

Unfortunately, it is not possible to confirm the animal's identification from the photo Mr Carter could get before the shark broke free of the net -- it does, however, appear to have been a lamnid (i.e., member of the Lamnidae family). There are also numerous reports of white sharks in the Minch and Little Minch (Western Isles of Scotland) stretching back to the mid-1990s, although there is no definite proof.

In December 2003 there was a report of a large shark, estimated at between 5.5m and 5.8m (19ft) long, caught in fishing grate near Pentland Firth, a channel between the Orkney Islands and the coast of northeast Scotland. The shark laid in the net snapping at the fish, before working itself free and swimming away. The fisherman didn't claim that the shark was Carcharodon, saying only that it wasn't a basking shark, but the photo taken showed a shark that looked very much like a great white. Mr Peirce told me that, had he phrased his question to the shark experts who saw the photo differently, i.e., without mentioning that it was caught off Scotland, this picture would probably represent the first proof of white sharks in our waters. This capture remains probably the most credible evidence, and certainly the most credible photo, of great whites in British waters to-date.

A year and a half after the Pentland Firth capture, in July 2005, fishermen on a boat trolling for pollock (Pollachius spp.) about 3km (2 mi.) south of Locheport on the east coast of North Uist (Scotland) reported that a large shark, fitting the description of a great white, surfaced next to them briefly before disappearing. During the following year, a large shark was caught in a trawl net off Scotland; a photo was taken but it was impossible to be sure of the species.

Scotland was the source of another potential great white sighting in 2007. During late June or early July some interesting mobile phone video footage came to light showing what appears to be a large shark, estimated by the witnesses to be about 3m (10ft) long, attacking a seal in the Sound of Harris (Outer Hebrides, UK). Mr Peirce showed the video to several shark experts from around the world. Ian Fergusson and Leonard Compagno concluded that there was a 60% likelihood that the shark was a great white and a 40% likelihood that it was a shortfin mako, while Henry Mollet, Chris Fallows and Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch said that it could be either, but favoured it being a mako. Mr Peirce considered either a mako or porbeagle to be the most likely candidate.

There are some other tantalizing, if less detailed, accounts attributed as white sharks. In January of 1998 a large shark, estimated at more than 5m (16.5ft) long and weighing about 500kg (1100 lbs), was seen chasing seals that had been attracted to salmon cages in Sandsound Voe, off the west coast of the Shetland Islands; some shark biologists have suggested it may actually have been a sixgill (Hexanchus griseus), rather than a great white. Similarly, reports of large brown sharks being caught and released off the Cornish coast during the mid-1990s were probably Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus). In July 1999, a large shark apparently followed kayakers up and down the coast in the Sea of Hebrides in western Scotland and seemed to be the reason local seals refused to come off the rocks. The kayakers returned to the bay the following day and found what they described as a seal bitten in two, but, unfortunately, no photos were taken.

Finally, in September 2014, an article appeared in the Daily Express carrying stills from a video taken by Nigel Hodge, a Cornish fisherman, about 20 miles off the Falmouth coast. The video appears to show a 14ft white shark swimming past his boat. Shortly after the video made the press, the Shark Trust's Ali Hood told The Telegraph that it was actually a juvenile basking shark, while others suggested it was an oceanic whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus). It is difficult to tell from the video, but it certainly appears to be a lamnid shark and it looks very much like a great white. In the event this could be confirmed, and the location verified, this would represent the most conclusive video evidence of white sharks in UK waters that I have seen to-date.

In terms of indirect evidence, I have heard rather vague reports that fishermen have apparently seen white sharks taking seals in the Bristol Channel, but I have yet to see any convincing evidence of this. There is, however, one interesting record of a badly injured seal that washed ashore on the Welsh coast; photos were taken (and recently declassified) and from the bite mark forensics, Shark Specialist Group biologist Ian Fergusson suggested that it could have been a white shark attack. The report is interesting because it is from a whole seal that was otherwise relatively fresh.

Why? Why not?

Rather than questioning whether a white shark would visit, or live around, the UK we should perhaps be asking ourselves why we have not come across them off our coast before. The water temperatures off the south coast of England have an average range of 6C to 20+C (43-60+F), which is perfectly within the white shark's 3.4C to 26C (38-79F) tolerance. We also have a large population of seals -- about 50,000 common (Phoca vitulina) and 120,000 grey (Halichoerus grypus) -- and we know that pinnipeds represent a significant food source throughout parts of the great white's range. Finally, white sharks are known to travel quite remarkable distances and a paper published in the journal Science during 2005 tracked a female white shark (named Nicol) 22,208 km (13,800 miles) from the tagging site off South Africa to Australia and back; South Africa to Australia was completed in 99 days. Indeed, white sharks are the most wide-ranging and widely distributed of all shark species for which we have data, and specifically why we don't see them off the UK is something of an enigma.

The most northerly historical record for white sharks in the northeast Atlantic was from the mouth of the Loire in the Bay of Biscay off the French coast and comes from a set of preserved jaws. In addition, three men fishing slightly farther south -- at Pertuis d' Antioche, off La Rochelle -- caught a 2.1m (7ft) juvenile female great white in their nets on 24th May 1977. Great white sharks are also well known from the Mediterranean Sea, even to the extent that some authorities have suggested certain parts of the Med may be a breeding ground for this species. For the Atlantic as a whole, the most northerly records for white sharks come from the northern sections of the Gulf of St. Lawrence off Newfoundland in Canada, the same latitude as the English Channel.

Briefly, it is worth mentioning that great whites seem to travel farther north in the Pacific than in the Atlantic; reports exist as far north as Siberia, although the most northerly confirmed record was from the south-eastern Gulf of Alaska, which is on approximately the same latitude as the Outer Hebrides. One specimen was reported in a short communication to the journal Copeia by fisheries biologist William Royce back in 1963. The shark stranded at Craig in S.E. Alaska around October of 1961 and was said to have been 15ft 4in long (approx. 4.7m) with a girth of about 9ft (2.7m).

Perhaps the best endorsement of how unsurprising it would be to find a white shark off the UK, from an ichthyological perspective, comes from the eminent shark scientist Professor Leonard Compagno at the South African Museum in Cape Town. In his 2001 revision of the Sharks of the World catalogue, Compagno has extended the range of the great white to the English Channel, North and Irish Sea. Compagno writes "possibly England" when listing known locations for this species. As we have seen, however, without tangible evidence we must stop short of proclaiming UK waters the playground of Carcharodon carcharias.

Of course, despite all the reasons why great whites should be found in our seas, there is one very good explanation for their apparent absence: their global scarcity. Ex-fisheries biologist, Doug Herdson, is reasonably convinced that white sharks are now so rare in the North Atlantic that the chance of spotting one in our waters is vanishingly small. In an interview with the BBC, Doug said: "Temperature and conditions here are all fine, and I'm sure they have been here in the last 3-4,000 years, but they are now so rare it is very unlikely."

Additionally, some have suggested that, given the extent of Britain's fishing industry, if white sharks were around, we'd have caught one by now (but, have we?). I'm certainly more receptive to the suggestion that the depletion of our fish stocks -- despite the mammals in their diet, great whites are primarily fish-eaters -- may simply mean there isn't sufficient food to support a resident population of white sharks. While I doubt this is the whole story, is does tie, at least coincidentally, into the suggestion that the vast shoals of mackerel, herring and pilchard that used to migrate along the south coast of Britain prior to the start of the 20th century were occasionally followed by white sharks. In his fascinating book, The Unnatural History of the Sea, Callum Roberts mentions this, although he doesn't cite a source:

"Porpoises and dolphins were just two among the host of predators in pursuit of schooling fish. They were joined by sharks; the large porbeagle, blue, mako, and thresher sharks were common hunters of European seas and were occasionally accompanied by great white sharks."

Possible contenders

If the aforementioned sightings weren't white sharks, what other species could they be? We've already come across species such as the mako and porbeagle. Both of these species are relatives of the great white (i.e., members of the same family, the Lamnidae) and, as a consequence, look similar; but are they genuine contenders? The shortfin mako is a large, fast moving, predatory shark, which is predominantly a summer visitor to UK waters. There are sporadic records of makos from the Bristol Channel and a handful from Scottish waters and the North Sea, but these sharks are predominantly found along the southern coasts of Ireland and England, as far east as the Isle of Wight. The porbeagle is also a large predatory shark and is morphologically more similar to a great white, perhaps allowing the uninitiated to more easily confuse the two. Porbeagles appear to be present year-round in UK waters, although relatively recent unregulated fishing off the coast of south England may have substantially decreased numbers.

It's one thing to say that makos and porbeagles bear a family resemblance to white sharks, but do they match up in terms of size and diet? Well, generally neither species attains the same mature lengths as the great white. It has been suggested that shortfin makos reach a theoretical maximum of just over 4m (13ft) -- although, interestingly, a report of two makos caught in a salmon net off the coast of north Yorkshire put one animal at about 5m and the other larger -- with an average closer to 2.5 or 3m (about 9ft). The porbeagle has a probable maximum length of just less than 4m, with British-caught specimens averaging 1.5 to 2m (about 6ft). White sharks, on the other hand, can reach at least 6m (19.5 ft), although they mature at anywhere between 3.5m and 5m (11.5 to 16.5 ft.) depending on sex. In terms of diet, all three species are heavily piscivorous (fish-eaters); indeed, the great white feeds predominantly on fish throughout its life cycle. As almost anyone who has watched Shark Week will know, however, upon reaching maturity white sharks expand their diet to include a greater proportion of marine mammals, especially pinnipeds, although new research suggests this may be sex-dependent.

The same is not true -- at least, not to the same extent -- of either the mako or the porbeagle. Indeed, the porbeagle appears to feed exclusively on fish and cephalopods (mainly squid). Makos are predominantly fish-eaters, although larger individuals may take prey up to the size of a small dolphins -- pinnipeds haven't been recorded in their diet, although in his 2001 revision of Sharks of the World, Compagno noted that these mammals may be taken where their range overlaps with large makos.

So, in terms of size, smaller white sharks may overlap with larger makos; but, when considering culprits for possible shark bite-related mortality of seals, as opposed to the scavenging of dead animals, both porbeagles and makos seem unlikely suspects. Nonetheless, many sightings of free-swimming white sharks from UK waters could easily have been porbeagles or makos. Without proof one way or another, one tends to err on the side of caution.

In conclusion...

To sum all this up, despite Britain's seas being well within the expected range for white sharks, there is still no indisputable evidence that they're here. Several very credible reports exist providing very compelling accounts of white shark appearance and behaviour, and it's interesting to note that the most credible reports have come from either north Cornwall or western Scotland.

Until conclusive proof is presented, however, UK great whites are resigned to the "possible, but unproven" file, along with reports of nurse, bull and tiger sharks (see: Sharks and Rays in British Waters).

Addendum: I am indebted to Ian Fergusson for taking time out of his busy schedule to provide me with information and references pertaining to the northerly distribution of the great white shark and to Richard Peirce for running through some of the shark sightings and providing his appraisal of them. My thanks are also extended to Adrian Brayshaw for his account of the Blue Fox encounter and to Robert Watkins, Mark Bradfield, Davey Benson and Douglas Herdson for their provision of, and comments on, other encounters.