Summary

Samson is a recessive genetic mutation of foxes (typically the Red fox, although it is known in other species) that prevents the long guard hairs that give the coat its lustre from growing and causes the underfur to be tightly curled. The result is that the fox has a ‘woolly’ appearance that may cover the whole body, or only tail and hind quarters, depending on whether the animal is a ‘complete’ or ‘partial’ Samson. Samson foxes tend to be larger than normal foxes and have a higher metabolism that provides them with a voracious appetite; they also have larger deposits of fat just under their skin and associated with their intestines that presumably helps compensate for the lost insulation that the fur would ordinarily provide.

The scant data we have on these animals suggests they prefer to live around human settlements where they feed heavily on garbage. No recent work has been conducted on the genetic basis for the Samson trait and its origin is unknown; some suggest that it may have arisen in fur farmed animals and made it into the wild via escapees, although this seems unlikely.

Occasionally, completely hairless animals are found (particularly in the USA), but these are alopecic foxes rather than Samsons.

The Details

Red foxes come in an impressive range of colours and patterns, from jet black to pure white, with most hues of red, orange and yellow in between. The coat is composed of two main hair types: relatively short (ca. 35mm or 1.5 in.) fine grey underfur, sometimes called "vellus hair", that covers the back and sides and provides insulation; and the longer, thicker guard hairs (or "terminal hair") that provide waterproofing and give the coat the shiny lustre so highly prized by hunters and fur farmers alike. Occasionally, however, the guard hairs fail to develop and the coat takes on a "woolly" appearance. These foxes are called Samson foxes, presumably deriving their name from the biblical character that lost his power when the Sorek temptress Delilah ordered a servant to cut off his hair. The Samson character can be expressed partially or completely: partial Samsons lack guard hairs around their rear end and on their tail, but the remainder of the fur is normal; complete Samsons lack guard hairs across their whole body.

A lack of guard hairs is not the only feature by which Samsons are distinguished from normal foxes. In a 1951 paper to the journal Papers on Game Research, Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute biologist Teppo Lampio described how Samson foxes are typically larger than normal animals, with a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat (that held just under the skin) and considerable amounts of fat associated with the intestines, which contributed to the animals being heavier than regular foxes; he suggested that this fat may provide insulation, possibly helping to compensate for the lack of guard hairs. Other traits noted by Lampio include 'clearer' footprints (there was only woolly fur on the underside of the paws, and even this was often worn away) that were narrower than those of normal foxes; claw marks were rare because the animals apparently wear down their claws quickly digging for food. In captivity, where food is provided, the claws apparently grow long and sharp.

Lampio goes on to describe differences in the behaviour of Samson foxes, commenting that they tend to live around human settlements and are thus very accustomed to human activity. Indeed, Lampio wrote that they were: "so bold as to be met in the middle of the day near the yard of a house". Granted, compared to modern day urban foxes such behaviour may be of little surprise, but these accounts are of foxes in a hunting community during the 30s and 40s.

The implication of Lampio's summary is that Samson foxes are less well adapted to survive and find food in the wild than their fully-furred counterparts and this explains their preference for living in such close proximity to humans; he described how a Samson will feed largely on refuse and "does not even shun the excrements of domestic animals", which appears to refer to cattle dung. It seems that these Samsons were well-adapted to feeding on garbage and in an earlier study, published in 1948, Lampio found they were less susceptible to certain lung and intestinal parasites (which might be picked up scavenging) than regular foxes. There are, however, other explanations for this, which we'll look at shortly. Finally, Lampio noted that experience of Samsons in captivity showed their cubs to be less viable (i.e., fewer survived) than normal fox cubs; initially they grew more slowly, although they caught up later on, were "obviously ill-tempered" and had an "abnormally large appetite". It seems probable that these animals were at a competitive disadvantage to their normally-furred conspecifics.

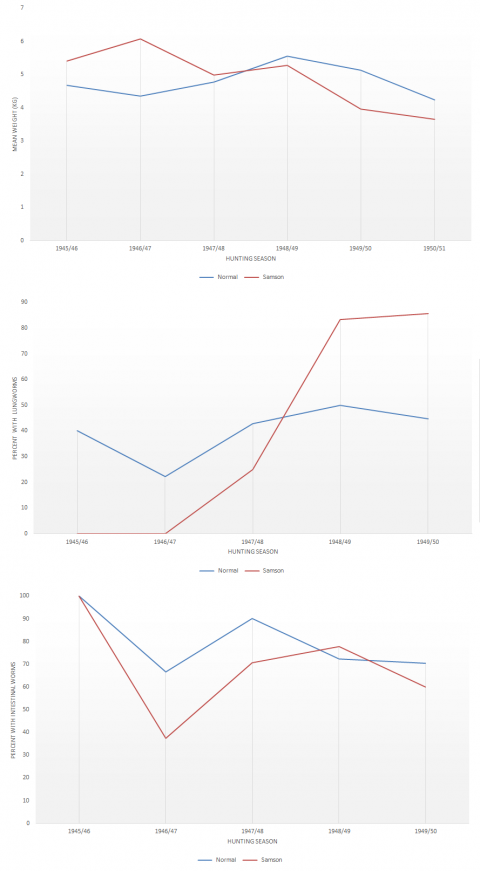

Interestingly, it appears that Samson foxes were healthier during the early part of the Finnish population explosion than later on, and this is reflected in both the average weights of the animals caught and the number found with lung and intestinal worms. Presumably, when the population first became established and began to grow there were relatively few animals, meaning competition for resources was low; as the population increased so did competition between the foxes. The graphs below show the data that Lampio collected on Samsons shot by hunters in Finland between 1945 and 1951 and they imply a change in the fortunes of the population around 1948. Caution should be used when drawing any firm conclusions from these data because Samson individuals are relatively uncommon and the graphs are based on relatively few animals.

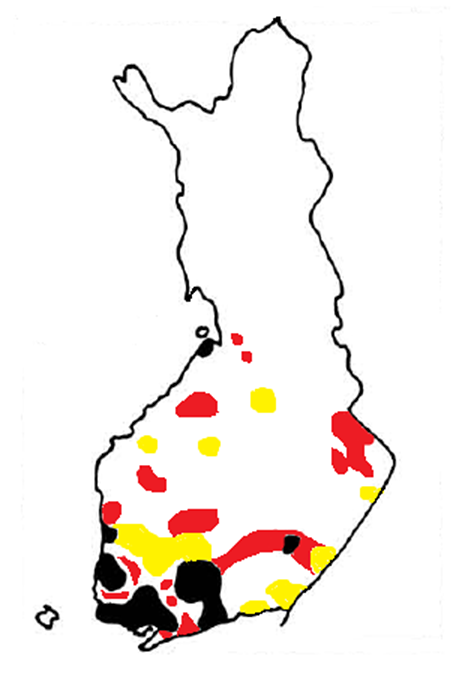

Despite the changes, Samson foxes were still able to spread throughout much of southern Finland by the end of the 1940s. Indeed, by the 1946-47 hunting season, these animals accounted for 7.5% of the total catch, with substantial local variation (some populations had 80% Samsons). The distribution of Samsons remained relatively stable during the 1950s, but by 1960 there were only isolated populations based predominantly in the south of the country.

The origin of Samson

In the Bible story, the Philistines approached Delilah and offered her cash to find out the source of Samson's great strength. Much trial and error on Delilah's part, and seemingly much teasing on Samson's, led to the discovery that his hair was the crucial factor. In a similar manner, many theories have been proposed to explain the origin of the Samson character in foxes, not least because it is an economic disaster for fur farmers and many hunters; the pelt is virtually worthless. I have been unable to establish when the first Samson fox was documented but such foxes have been recorded on Finnish fur farms since at least the 1920s.

Northern Europe appears to be something of a "hub" for these animals and most of the early (1930s and 1940s) records of wild Samsons come from Finland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Indeed, the appearance of these animals in areas with established fur farms led some to theorise that the character originated in captivity and made it into the wild when animals escaped. Deliberate releases also happened from time-to-time and Lampio pointed out that, at the request of the Ministry of Agriculture, about 225 silver foxes (a black colour morph of the Red fox) were released into different parts of Finland during 1937/38 in the hope they would cross-breed with the native foxes and make the wild stock more valuable.

The problem with the theory of Samsons originating from fur farms is that, as even Lampio noted, the earliest Samson foxes pre-date known releases and some even maintain that they pre-date the establishment of fur farming in Finland. It has also been argued that, if the appearance of the Samson character indicates escaped/released stock, we should expect more silver and "smoky red" foxes in the wild populations than were observed, because these are the colour morphs likely to have been released as well. In fact, wild black foxes were very rare in Finland, but common on farms. Furthermore, given that the releases we know about were undertaken with the aim of improving the wild stock, it seems unlikely that foxes with a mutation that devalued the pelt would be consciously released. Overall, it seems more likely that the character appeared spontaneously in the wild population and, because the fox population was very low at the time, close to being exterminated in fact, the mutation was able to gain a foot hold in conditions where competition with normal foxes was low. This theory also goes some way to explain the decline in Samsons during the late 1940s and 1950, as the population of normal foxes recovered.

Some early fur farmers considered that the Samson character was actually a disease; a response to a parasite infection or to the poor nutritional condition of many farmed foxes, owing to their heavily vegetable-based diet. Not everyone agreed, however, and some considered this was a genetic trait. Between 1947 and 1950, University of Helsinki geneticist Tarvo Oksala conducted breeding experiments with Samson foxes and the preliminary results were published in Papers on Game Research during 1954. Oksala had problems getting some of the foxes to breed in captivity, but was nonetheless able to make some interesting observations from the limited success he had over the three years of his study. When he bred two wild-caught complete Samson animals, Oksala ended up with four complete Samson cubs. Given that Samson and normal foxes were kept in the same housing and given the same diet, these cubs provided a pure Samson line that implied diet was not a significant factor. Oksala wrote:

"This does not imply that [disease or environment] would not influence the Samson character, strengthening or weakening its expression. On the contrary its great instability suggests this very possibility. But the ultimate cause must be an inherited disposition."

When Oksala talks of the "great instability" of the Samson character, he is referring to his observation that foxes can apparently grow in or out of it. During his study, Oksala found that some of his Samson animals moulted into normal fox coats and vice versa. One male caught as a "normal" cub in the south of the country during 1946 moulted into a Samson in its first autumn and then guard hairs grew back in the autumn of 1948. Also in 1946, this time in west Finland, a young male fox was caught with a normal pelt; in the autumn of 1948, however, he "changed into a fairly typical Samson fox". At the same time, the three other Samson animals (a male and two females) maintained the character for the duration of the study. These findings caused Oksala to ponder the potential mechanisms of transference from parent to cub.

Oksala noted that, because the Samson character is of no commercial value, fur farmers do not breed from affected animals and yet the condition cropped up frequently on farms; this observation, and the results of his first breeding experiment, led Oksala to conclude that the trait must be recessive (i.e., only appears when two copies of the particular allele are present). He goes on to say:

"It is tempting to suppose that selection in natural populations has created a modifier system which, when complete, is able to neutralize the effect of the gene or genes which give rise to the Samson character."

In other words, another gene or gene complex can override or "switch off" the Samson gene(s) and allow the normal growth of guard hairs. Genes can be switched on and off by the cell's machinery during one of two genetic processes: transcription and translation. The ability to turn a gene coding for the Samson character on and off might explain how animals can moult between the two conditions. Unfortunately, to the best of my knowledge, no detailed genetic or dermatological studies have been conducted on Samson foxes and so the specific gene(s) responsible, as well as its origin, remain unknown.

The Samson condition is not unique to Europe or to Red foxes. In 1974, Fish and Game biologist Stephen Allen estimated that about 5% of North Dakota's Red foxes had the Samson character. Allen tagged six normal cubs from the same litter in 1970; two shot in 1971 were normal, but two shot in ‘72 had developed the Samson condition. Samson Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) have also been recorded and, in a short paper to the Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, University of Wisconsin biologists David Root and Neil Payne described a male complete Samson Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) that was shot in Richland County during late November 1979. The Wisconsin Grey Samson was in good condition and estimated to have been less than a year old. It seems that other members of the Canidae (dog family) are susceptible to the condition and Samson Raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) are occasionally recorded in Finland. Outside of the canids, the "rex" condition of rabbits and "crinkled" character of mice is similar, although not identical, to the Samson character of foxes.

Hair today, gone tomorrow

Occasionally, completely hairless foxes have been recovered and several were photographed in the USA relatively recently. In May 2004, a gentleman in Asheboro, North Carolina, photographed a bald fox, that he initially thought was an escaped dingo, feeding on corn in his backyard. A similar animal was seen several times in the Piedmont, on the east coast during the same year. Subsequently, in 2006, another hairless animal was photographed in the Piedmont, and one hit by a car and killed in Charleston, South Carolina. Initially, both animals were considered to have been Samson Grey foxes; but, the Charleston animal was examined by Jaap Hillenius, a biologist at the College of Charleston, who found that it lacked hair follicles in its skin and so was apparently incapable of growing hair.

A similar-looking animal was photographed foraging in a field in Raleigh, North Carolina during 2006 by Jerri Durazo. Durazo's photo was sent to North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission biologist Perry Summer, who suggested it was a Samson fox (misspelt "Sampson" in the National Geographic article on the subject). Since these cases, there have been several reports of hairless foxes, including one bald Red fox that made CNN news in September 2009 when it was filmed stealing golf balls from a garden in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. More recently, during December 2011, a Samson fox turned up in the backyard of North Carolina resident Staci Wood. The animal was caught on her trailcam and she kindly sent me her pictures to accompany this article.

Interestingly, it seems that, in some of the above cases, the definition of a Samson fox is being used more broadly than either Lopio or Oksala considered it. As we have seen, according to these authors (and most subsequent ones) Samson foxes aren't bald; they simply lack guard hairs. Given that several of the recent examples lacked fur altogether, it seems there is a separate character being expressed here. This is particularly apparent if, as was the case in the Charleston animal, hair follicles are missing from the skin, making it impossible for the animal to grow the curled underfur previously described, let along spontaneously grown a normal coat at a later stage. On one Internet message board, a hunter claimed to have regularly trapped and shot Samsons (this board represents the first instance where I have seen Samsons referred to as "Cotton foxes") in South Carolina, and noted that you can't normally tell it's a Samson until you get close (although all his were a striking yellow colour); this ties in with accounts from Oksala and others. Indeed, Lopio noted that some foxes presented with very little or no underfur, but considered this to be a separate condition. To avoid potential confusion, it seems prudent to consider hairless animals to be alopecic foxes, rather than Samsons.

It is also worth mentioning that there are various disorders than can cause temporary hair loss, including malnutrition and severe cases of mange -- in both cases, fur growth returns to normal once the animal has recovered. Furthermore, a study of Red foxes on the Japanese island of Hokkaido during the late 1980s found that an inflammation of the dermis (top layer of the skin) can lead to the death of hair follicles and cause the hair to fall out; this is a condition referred to as hypotrichosis.

In a fascinating paper to the journal Polar Biology during 2007, University of Iceland biologist Pall Hersteinsson and his colleagues presented the results from their detailed study of hypertrichosis in Icelandic Arctic foxes. Hersteinsson and his co-workers found that hypotrichotic foxes presented with scarce or absent guard hairs and very thin underfur; in severe cases, the animals were almost hairless. These foxes shared other features in common with Samson animals, including a voracious appetite in winter (presumably a reflection of the loss of insulation and associated high metabolism), slower growth of cubs, lower survival rates of cubs and adults, and ill temperament in captivity. It seems that this condition has been known in Icelandic foxes since at least the 1930s; the earliest written record, from 1932, described cubs born without fur (or that lost their fur soon after birth) and suffered from swollen joints. Additionally, a "sudden onset of severe coat damage and hair loss" was described by Margaret Hardy and colleagues in silver foxes on several fur farms in Canada during 1985; a histological study by Hardy and her co-workers, published in 1991, suggested a random genetic aberration but no trigger was identified.

Hersteinsson and his team found that the hypotrichotic cubs they caught in the wild and reared in captivity grew much more slowly than, and never attained the same adult weight as, normal cubs. Interestingly, they also observed that hypotrichotic vixens were more fecund (i.e., produced more cubs) than normal vixens, while hypotrichotic males were less likely to breed than normal ones. Both sexes were more affected by winter air temperature (doing better in milder winters) than normal animals, which is expected given their lack of fur. The skin of hypotrichotic animals was inflamed, the hair follicles had started to die and, although they were unable to find the cause of the condition (i.e., a bacteria, fungi etc.), they suggested that it was the work of an infectious agent transmitted from mother to cub.

In conclusion, Samson foxes are those animals suffering from a heritable recessive genetic condition that can potentially develop and regress as the animal moults. Samson animals differ from normal animals by the lack of guard hairs and from alopecic animals by the presence of underfur. The loss of fur guard hair appears to impose physiological costs, including a higher metabolic rate to compensate for heat loss. The specific genetic basis for the Samson condition remains unknown and individuals remain rare in the wild.